After months of confusion over the future of a much-vaunted mission to bring samples from the Red Planet to Earth, NASA has its verdict on the return of samples from Mars.

The space agency is “committed” to bringing those rocks back from Mars, administrator Bill Nelson said Monday, but it will have to do so with much less money and in much less time than currently designed.

And how exactly is NASA going to achieve this? Right now he has no idea and is looking for someone who does.

“I have asked our people to reach out with a request for information to the industry, to [the Jet Propulsion Laboratory] and to all NASA centers, and to report this fall on an alternative plan that will get [the samples] come back faster and cheaper,” Nelson said at a news conference at NASA headquarters.

His comments came in response to a independent review commissioned by NASA last year that stated there was “near zero chance” that Mars Sample Return would meet its proposed 2028 launch date, and that there was no “credible” way to accomplish the mission within its current budget.

Carrying out the mission as designed would likely cost up to $11 billion, the review board found, and samples will not reach Earth until at least 2040.

“The bottom line is that $11 billion is too expensive, and not returning samples until 2040 is unacceptably too long,” Nelson said. “It is the 2040s when we will take astronauts to Mars.”

The announcement is something of a blow to JPL, the La Cañada Flintridge institution in charge of managing the mission. JPL has already laid off more than 600 employees and 40 contractors this year after NASA ordered it to reduce spending in anticipation of budget cuts caused by the challenges of the Mars Sample Return.

Proposals will soon be sent to all NASA centers and the private aerospace sector for “a revised plan that uses innovation and proven technology to reduce risk, reduce costs, and reduce mission complexity so we can return these truly precious samples.” to Earth in the 2030s.” ”said Nicky Fox, associate administrator of the Science Mission Directorate. The deadline for proposals is next month, and those selected for additional studies will receive grants from NASA this summer.

This basically puts JPL in a position of having to compete for its own project.

“Right now, if JPL had the answer, then I would say JPL will be pretty good,” Nelson said during Monday's news conference. “But we're opening this up to everyone because we want to get as many new, fresh ideas as we can.”

NASA's decision to outsource a solution to the Mars sample return problem frustrated some Mars scientists.

“What I was hoping for is that NASA would step up and say, 'These things are hard and we choose to do them,'” said Bethany L. Ehlmann, a planetary scientist at Caltech. “That is the leadership that is required to be the world's leading nation in space exploration.”

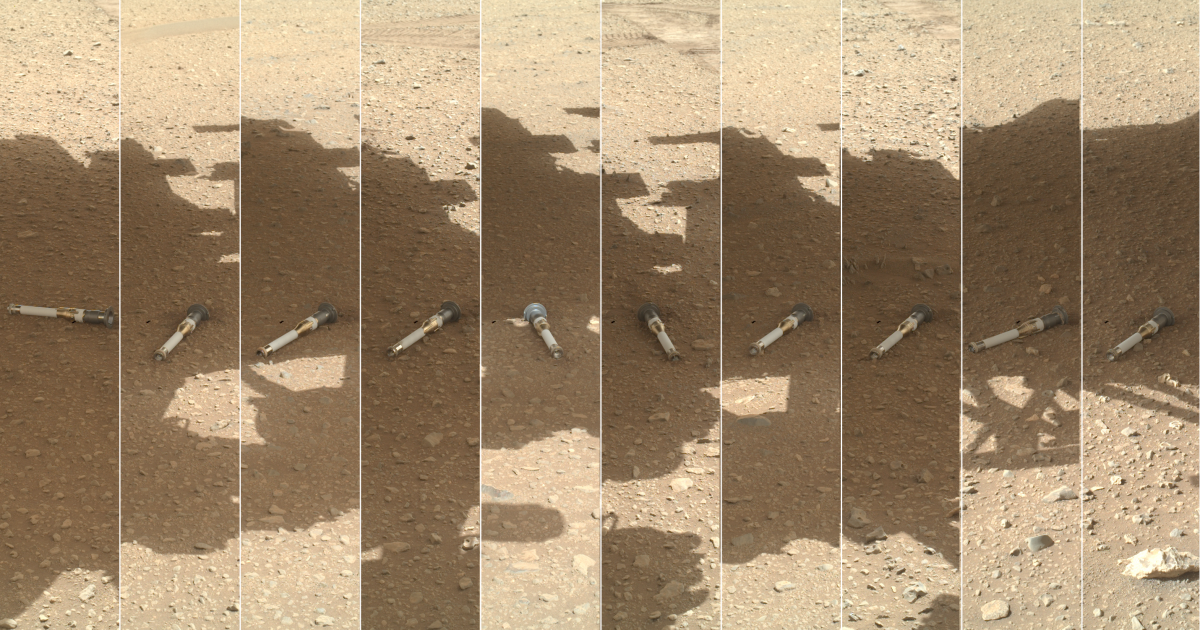

Mars Sample Return, a joint project with the European Space Agency, would deliver rocks, debris and dust that the Perseverance rover has already gathered and sealed in tubes.

The current design is based on a lander that would retrieve those tubes from the Red Planet's Jezero Crater and use a small rocket to transport them into Martian orbit, where they would meet a spacecraft that would make the return trip to Earth. The rocket would land on Earth approximately five years after the orbiter launched.

The ultimate goal is to analyze the samples for evidence that life once existed on Mars and help NASA plan future crewed missions, Nelson said.

In the most recent decadal planetary science surveya report prepared for NASA every 10 years by the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and MedicinePlanetary scientists named the Mars Sample Return mission the “highest scientific priority of NASA's robotic exploration efforts this decade” and argued that the program should be completed “as soon as practically possible without increasing or decreasing its current scope.” “.

But the authors cautioned that the ambitious mission should not come at the expense of other planetary science, suggesting a cap of roughly $5 billion to $7 billion.

“Mars sample return is of critical strategic importance to NASA, American leadership in planetary science, and international cooperation and must be completed as quickly as possible.” the report said. “However, its cost must not be allowed to undermine the long-term programmatic balance of the planetary portfolio.”

The agency is committed to keeping the mission within the recommended budget, Nelson said. Allowing Mars Sample Return costs to reach the $8 billion to $11 billion the review board estimated would require NASA to “cannibalize other programs, other science programs, and there are many that are absolutely important,” Nelson said.