Political opponents glared at each other from their campaign tables outside the Wilmington Recreation Center.

Alejandra Rodriguez’s exhibit included pamphlets about her identity and a framed poster of her in front of the Banning Museum. Her boisterous mother told everyone nearby why Rodriguez should be Wilmington’s next honorary mayor.

Alicia Baltazar and her son served free fries, homemade mini-muffins and his His own campaign poster: a portrait of him in front of the cargo cranes that serve as the southern horizon for the port community. But there was a problem: The poster kept falling off a flimsy cardboard backing.

Rodriguez walked over and set up a small metal A-frame.

“Thank you!” said Balthazar gratefully.

“Thank you!“Rodriguez, 38, exclaimed with a genuine smile.

“See what I mean?” Baltazar, 46, told me. “We’re competing together, against each other!”

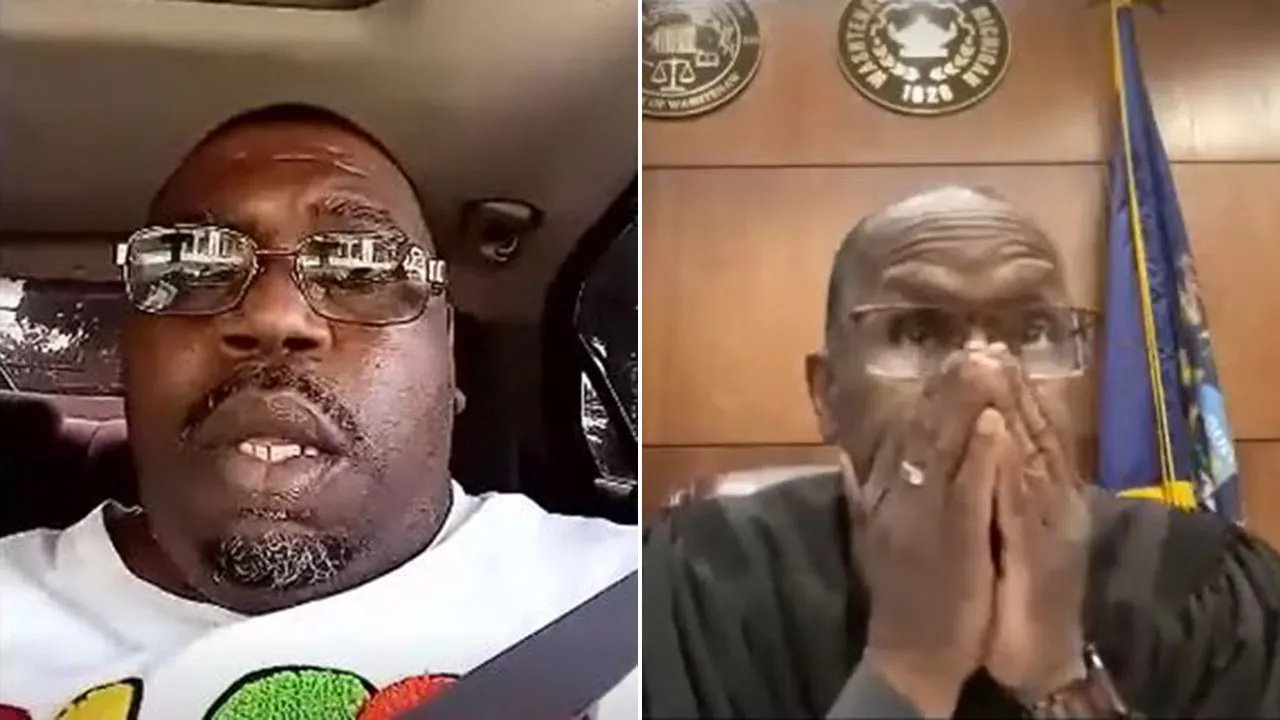

Alejandra Rodriguez, left, and Alicia Baltazar applaud during a ceremony for the announcement of Wilmington's honorary mayor on June 27, 2024, in Wilmington.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

The encounter was a regular occurrence in one of Southern California's healthiest political contests.

For the past 70 years, Wilmington residents have competed to become the working-class community's honorary mayor. The winner gets a two-year term that offers no salary, no staff, and no political power. No votes are cast and no political action committees are formed.

The position is a relic of an era when dozens of Los Angeles communities appointed prominent figures for promotional purposes, usually movie and television stars such as Steve Allen (Encino), Roy Rogers (Studio City) and Johnny Grant (Hollywood), who lived or worked in the area and whose duties primarily included posing for photographs during parades and openings.

Like Wilmington, which was once an independent city before becoming part of Los Angeles in 1909, these communities were unincorporated, so they had no traditional mayors or city councils.

At one point, the honorary mayors formed an organization to “find out how to serve a more useful and functional purpose for our communities and the city of Los Angeles,” according to a 1965 Times article.

According to a Times article from that year, there were still at least 20 communities that elected an honorary mayor in 2001. Today, only a handful remain, including Wilmington, San Pedro, Pacific Palisades and Woodland Hills, where former Los Angeles Councilman Dennis Zine holds the title.

“Part of it has always been gimmickry — the Sunshine State and the Sunshine City,” said Jaime Regalado, a professor emeritus of political science at Cal State LA who traces the tradition back to the 1920s and the rise of Hollywood. “But I don’t think they matter anymore. Cities have grown up over time and have discovered that the role doesn’t carry the prestige that comes with it.”

Wilmington has always had a reputation for making its honorary mayors work for, well, honor.

Candidates attend community events, organize fundraisers, stand on street corners, knock on doors and ask wealthy individuals and businesses to shell out a little more than a dollar, just as if it were a real political campaign. The winner is the one who raises the most money for a local nonprofit of their choice, mostly by selling one-dollar tickets.

“We’re old school,” said Wilmington Chamber of Commerce Executive Director Monica Diaz when I asked her why the city continues to do it the way it does. “It’s friendly competition, but we’re talking about people who represent their organizations with a lot of passion. It’s a way to build local leadership, above all.”

This year’s honorary mayor will be announced at a Wilmington Chamber of Commerce event on Sept. 26. In 2018, the last time the race was held, the candidates collectively raised $41,200.

When I pressed Diaz on the benefits the winner would get this time, he mentioned riding in a convertible as grand marshal of a parade and free admission to Chamber of Commerce events. “We could give him a sash, I guess!” he added.

I saw Baltazar and Rodriguez in action last month at a Summer Night Lights event, hosted by the Los Angeles Mayor's Office of Gang Reduction and Youth Development in parks across the city.

Baltazar, who describes herself as an “army daughter,” sees running for honorary mayor as a way to give back to the community she has lived in the longest (nine years). She is raising funds for Tianguiz Cultural, which organizes night markets in Wilmington and San Pedro.

“I love that my son can’t miss school without someone calling me. If I get a flat tire, someone will help me,” said Baltazar, a community activist and parent leader who serves on an advisory committee for Los Angeles Unified Board Member Tanya Ortiz Franklin. “I want to build a town for my son, and Wilmington offers that.”

She remained silent. “I almost want to lose so I can run again and raise even more money.”

Rodriguez is campaigning for the Wilmington Teen Center, which she frequented as a child because it was across the street from her family's apartment.

She wanted to run in 2018, but, she said, “I didn’t think I had a chance of winning. This time I realized that it’s not about who wins, because in the end, everyone wins.”

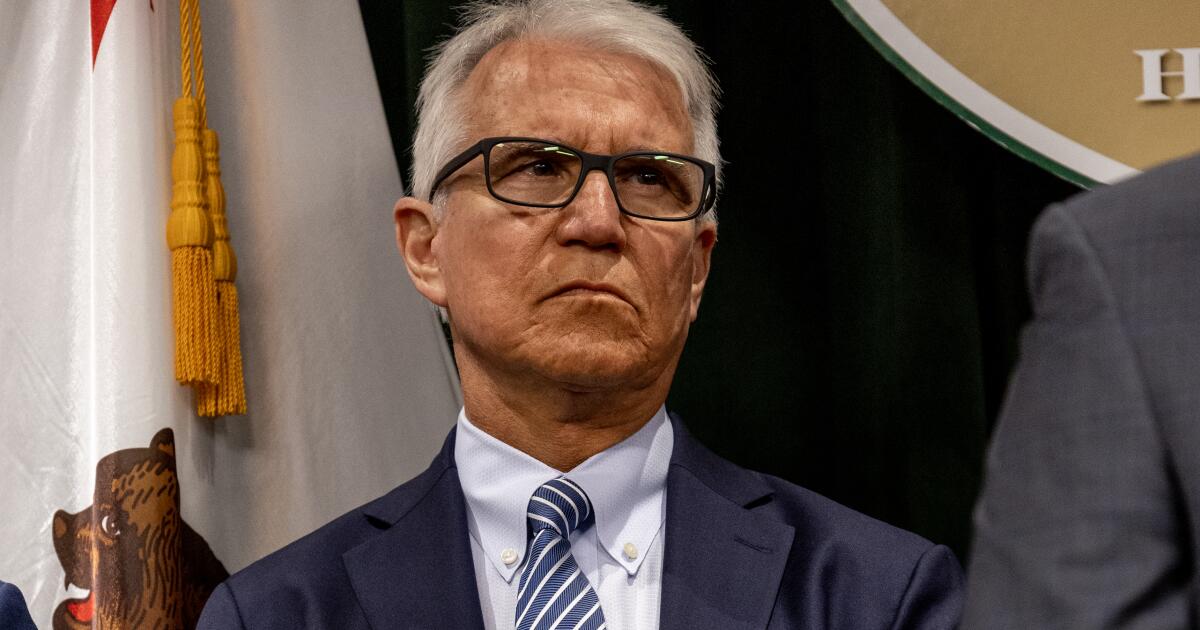

Alicia Baltazar, right, talks with Kevin Carle as he looks over his t-shirts made to raise money for his campaign at Calimucho Screen Printing on Sept. 16, 2024, in San Pedro.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

Technically, she wasn't campaigning on Summer Night Lights, because she was working as a district representative for Los Angeles City Councilman Tim McOsker, who represents Wilmington.

But his boss allowed him to talk to his mother from time to time to see how ticket sales were going.

“No, I’m not endorsing anyone!” McOsker said with a laugh, although he did donate $1,000 from his staff committee account to each of the four candidates: Rodriguez, Baltazar, Erick R. Ojeda Garcia and Cindy Guerrero.

“It’s the most inefficient way to raise money in the world – a ticket for a dollar!” McCosker added. “You’re just giving yourself away for free.”

The council member is from San Pedro, which has a similar honorary mayoral career.

“It’s very important to create community,” he said. “It’s a lesson for us.” [politicians]“Be close to the people you want to serve.”

At first, no one at Summer Night Lights paid attention to Baltazar or Rodriguez. Children ran around the lawn or drew at the art table. Mothers chatted at picnic tables. People walked their dogs. Men played basketball inside the gymnasium; families lined up at a large grill for free nachos and burgers.

A man holding a plate of two cheeseburgers eventually approached Rodriguez's table, only to tell his mother, Graciela Sepulveda, that he didn't care about politics.

“Well, you can still give a dollar,” Sepúlveda replied in Spanish. “If you don’t help, this kind of thing won’t continue to happen.”

The man, who did not want to give his name, stormed off, saying he didn't believe in anything. Sepulveda shrugged. “You're missing something!”

Shortly after, a woman approached Baltazar and then quickly walked away.

“That is my great downfall: I don’t speak Spanish,” Baltazar said dejectedly when I asked him what had happened.

But ticket sales began to pick up once the sun went down and adults realized what the race for honorary mayor was really about.

Rita Anaya bought two of Baltazar’s pieces. “It’s a very nice thing to do,” the Wilmington resident said in Spanish. “I really like his display.”

Next up was Alejandra Cervantes, who had never heard of the race despite living in Wilmington for more than 20 years.

“It’s a great idea,” he said in Spanish. “Politics is always about bringing people down and about power, and people get tired of that. But politics where all you do is help? I can get behind that.”

Cervantes then walked over and bought two tickets for Sepúlveda, who was doing a great job for his daughter.

But the delicious, free muffins beat the pamphlets any day. By the time I was about to leave, Rodriguez had sold 25 tickets to Baltazar's 56.

The breach did not dampen Rodriguez's spirits. At one point, Milvia Coloma approached Baltazar and spoke to him in Spanish. The candidate silently gestured to Rodriguez for help.

Once again, Rodriguez was happy to oblige Coloma. She explained how the race for honorary mayor works, but Coloma didn't understand why the rivals were helping each other. Weren't they both after the same thing?

“It’s good to cooperate to achieve good things,” Rodriguez said, prompting a nod of approval from Coloma.

“Okay, give me five,” he said to Baltazar. Then he walked over to Rodriguez’s stand and bought five more.