Throughout Los Angeles, Zachary Asdourian searched for the music of an Iran that could have been.

The co-founder of the Los Angeles record label Discochari searched for dust-covered Persian pop records at Jordan Market in Woodland Hills; I scanned flyers for shows at Cabaret Tehran in Encino, and scoured Glendale stores for Farsi-language tapes recorded in Los Angeles studios in the '70s and '80s.

Most of the songs he and his labelmate, Anaïs Gyulbudaghyan, were looking for were long-forgotten dance bangers, culturally specific twists on the disco boom of the era. They are poignant reminders of a time in the “Tehrangeles” neighborhood of Westwood in Los Angeles when, in the years immediately following the 1979 Iranian revolution, immigrants here made music as their homeland roiled with a rising theocracy.

Discotchari’s new compilation “Tehrangles Vice” compiles some of the best. Its 12 tracks were recorded in Los Angeles and circulated within the Iranian diaspora, then smuggled into Iran on dubbed tapes and satellite broadcasts. Here they are largely lost to time, but there they are fondly remembered as grandiloquent dispatches from a cosmopolitan but heartbroken immigrant community in Los Angeles.

Music has lessons for artists who observe the vindictive conservatism that grips the United States today.

“These songs were supposed to represent the next step in Iranian music,” Asdourian said. “These artists were geniuses in changing what was happening in the '80s and '90s to produce an Iranian version. This music was meant to be heard at a party while dancing and drinking in Tehrangeles, but it also provided solace during the Islamic Revolution, the Iraq War, and the Iran-Contra affair. For the citizens of Iran, this gave them hope while the bombs were literally falling.”

The music scene this compilation documents emerged after a period of more stable relations between the United States and Iran. Thousands of Iranian students immigrated to Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s and stayed, some opening restaurants and nightclubs in Westwood, Glendale and the San Fernando Valley where they could listen to Iranian music.

“Many of these clubs in Los Angeles predated the revolution. Artists like Googoosh were already coming from Iran to perform. Many musicians who were in the United States when the revolution occurred thought they were having a short stay and intended to return one day,” said Farzaneh Hemmasi, a professor of ethnomusicology at the University of Toronto, who wrote the book “Tehrangeles Dreaming: Intimacy and Imagination in Southern California's”. Iranian Pop Music” and contributed the liner notes to “Tehrangeles Vice.”

An insert from a cassette tape that Farokh “Elton” Ahi previously worked on.

(Emil Ravelo / For The Times)

“But after the 1979 revolution, the Los Angeles musicians were told by their relatives in Iran not to return, that they were rounding up artists, that people associated with Westernization and immorality would be attacked,” Hemmasi said. “So they stayed and worked.”

One of them was Farokh “Elton” Ahi, who came to Los Angeles at age 17 to study architecture at USC, but left that career to produce for Casablanca Records, the major record label of the time. He DJed at Studio 54 in New York and elite nightclubs in Los Angeles, and produced for artists like Donna Summer and Elton John at his Hollywood studio, Rusk (There he got his nickname from an interviewer who called him “Elton Joon,” a term of endearment in Farsi).

Even in the waning disco era, he felt an obligation to defend Iranian music in Los Angeles.

“We wanted kids to enjoy the link between our culture and Western culture,” Ahi said. “But we were also trying to draw people's attention to what was happening in Iran with our music, which was one of the reasons I was never able to go back there. The kids who had come from Iran loved Prince and Michael Jackson and were becoming super American, so we had to do something to keep them involved in our music as well.”

During the 1979 hostage crisis, Los Angeles Anglo nightclubs and radio were not interested in Persian pop music, to say the least. There he led a double life as an Americanized record producer and at the same time wrote for his immigrant community.

“Those days, because of the hostage crisis, it was not fun or games to have Iranian music in the club. People were against the Iranians and it was not a happy time,” Ahi said. “But we were making quality music with limited resources. There weren't many musicians here who could play Iranian instruments, so I had to learn a lot of them. I felt a duty to keep our music alive.”

Two '80s-era tracks he produced, Susan Roshan's “Nazanin” and Leila Forouhar's “Hamsafar,” appear on “Tehrangeles Vice,” which brims with L.A.'s unique cultural collusion of mournful Persian melodies and lyrics about exile, combined with new wave grit and '80s disco synth pulses. Aldoush's “Vay Az in Del” has sample instruments taken directly from the '80s television show that gives the compilation its name. There's even a strong Latin percussion element on tracks like Shahram Shabpareh and Shohreh Solati's “Ghesmat,” which showed how Iranian artists immersed themselves in the global crossroads of Los Angeles.

Even if this music didn't make an impact on the charts here, it found its way back to post-revolutionary Iran clandestinely, in tapes and music videos broadcast by satellite. Los Angeles-made club pop music gained new potency abroad.

“The official culture in Iran in the 1980s was very sad because of the war, and Shiite Islam was very mourning-oriented. Ramadan was a sad time without music,” Hemmasi said. “But in Los Angeles there are Iranians dancing and singing, which was not happening in the country, where people needed to sing and dance even more. This music had a contraband quality that was clandestine in Iran itself.”

“Many Iranian artists wouldn't like this comparison, but this music was really punk at its core,” Asdourian agreed. “There were people standing on street corners in raincoats selling cassettes. People had illegal satellite connections to listen to news and ideology from the diaspora that contradicted what they were being fed. This music was a means to restore the values they felt had been lost in the revolution.”

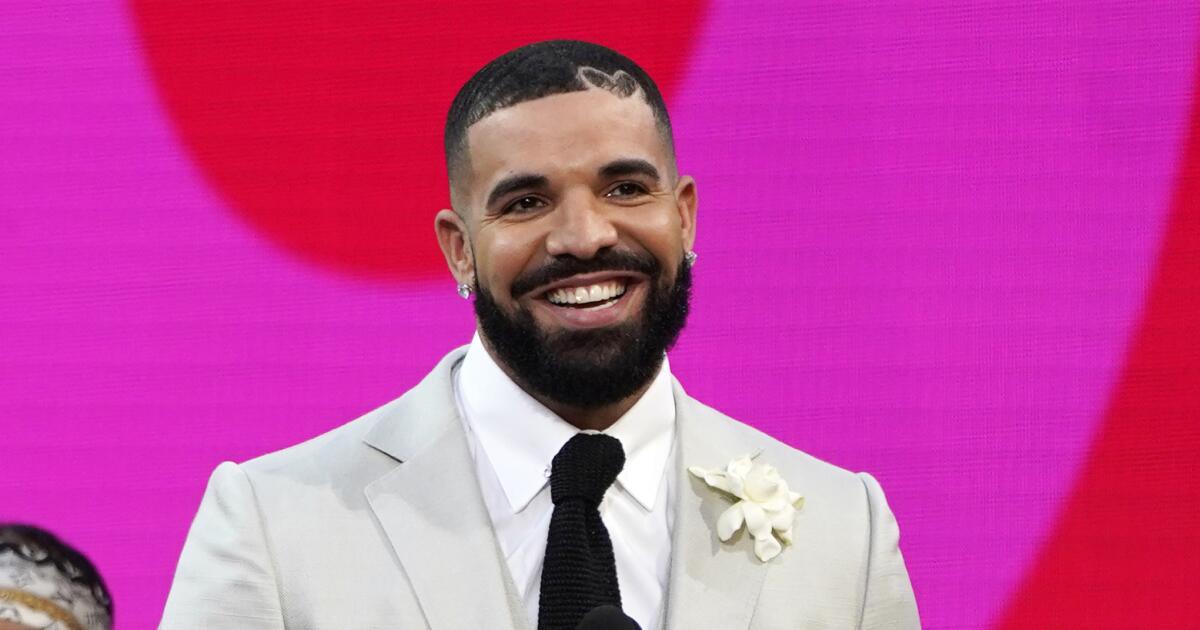

From top to bottom, Farokh “Elton” Ahi with Discochari record label founders Zachary Asdourian and Anais Gyulbudaghyan in Los Angeles.

(Emil Ravelo / For The Times)

As contemporary Angelenos rallying behind this era of Iranian music, Discotchari's Asdourian and Gyulbudaghyan will stop at nothing to send shady-sourced tapes from Iran, West Asia and the Caucasus to their label. “In January, we went to Armenia and met a guy who knew a guy in a restaurant in Yerevan who had someone bringing him tapes from Tabriz in Iran,” Asdourian said. “They sent us GPS coordinates to pick them up and we ended up in this abandoned former Soviet industrial district, being chased by a guard dog. But it had 30 cassettes, all still sealed in their boxes.”

However, some of the “Tehrangeles Vice” acts are still active, living and working in California. After a long hiatus, Roshan recently released new music inspired by Iran's Women, Life and Freedom Movement, and Ahi is a sound engineer and film mixer (he worked on “Last of the Mohicans,” which won an Oscar for sound mixing). He recently contributed to a remix of Ed Sheeran's “Azizam,” which mixes Farsi phrases with upbeat pop and became a global hit. “Ed came to me and asked me to write some melodies to match Googoosh's singing to make it more international, we put our minds together and I'm really proud of it,” Ahi said.

As the United States now has its own powerful right-wing religious movement in government, eager to suppress cultural dissent, “Tehrangeles Vice” offers lessons for musicians in the wake of a backlash. The compilation is both a specific document of a proud musical culture clamping down at home and flourishing abroad. But it is also a reminder that, whether created in exile or performed under attack, art is a well of possibilities for imagining another life.

“Even if the geographic location is not the same, for Iranians, Los Angeles represents this exiled piece of history, an Iran that could have been,” Hemmasi said. “It's a message in a bottle from another time.”