For traveling musicians, there are two versions of life on the road.

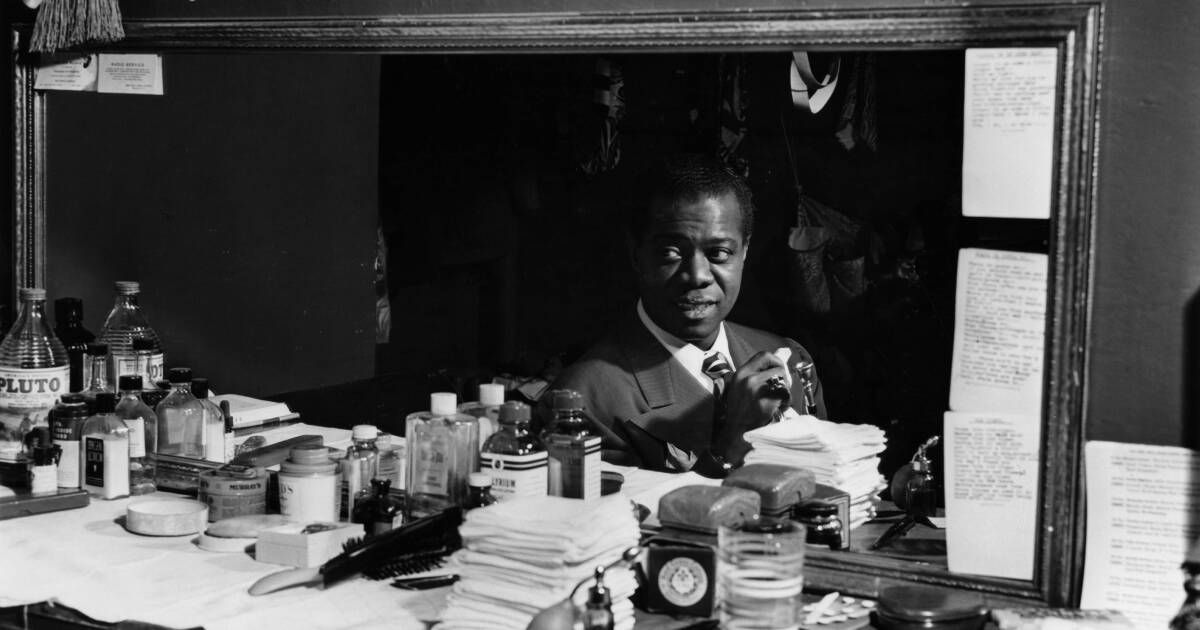

Jazz greats Duke Ellington, Count Basie and Louis Armstrong offered their own sentimental account of their nomadic existence from the 1930s onward, portraying the excursions as both amorous and glamorous, a veritable luxury cruise along bucolic roads packed with fawning fans. and a woman. fatal or two.

Much of that might have been true, but they also lived the other version of the walking life. Those trips, often through hostile territory, were a harsh crucible that kept Ellington, Basie and Armstrong away from home and family for lonely months. They became professional tramps, driving all day, performing until the wee hours of the morning, and learning to eat out of greasy paper sacks. On bad nights for conductors and their musicians, they slept a little on the bus or in the car, squeezed between sweaty orchestra mates. On a good note, they found a lodging house and ran upstairs, hoping to catch a nap before that night's concert. Smarter old-timers would leave the lights on to keep roaches and bedbugs in their crevices. Placing newspapers on top of the mattress was another trick; The crunching sound sent the vermin running.

Pulling back those curtains can be illuminating because the three jazz musicians of the last century helped set the blueprint for today's migratory music makers, whether they're Taylor Swift or Beyoncé. Whatever the reality of their days and nights on the road, Ellington, Basie and Armstrong created the expectation that traveling is about luxury accommodations and high salaries. Examining that melodious past (on the occasion of Duke's 125th birthday and the Count's 120th, as we approach the centenary of Satchmo's genre-defining Hot Five recordings) helps us not only separate myth from reality, but also to appreciate the ways our world has become better.

The biggest change since your time? The hostile terrain that Jim Crow America created for even the country's most revered black travelers. Accidentally choosing a whites-only hotel or restaurant could land a gang member in jail or worse.

Their travels attuned these three bandleaders to the subtleties and subtleties of America's color lines. You can't dine in the Chicago Loop. No entry at night, and sometimes no entry at all, to Goshen, Indiana, La Crosse, Wisconsin, and thousands of other “sundown towns.” And don't mention the Civil War below the Mason-Dixon line, because it was still called the War of Northern Aggression there. When the black musicians arrived, sometimes the gas station owners closed their bathrooms. Other times, their motel pool emptied just as they arrived and refilled when they left.

Ellington, Basie, and Armstrong successfully navigated that dangerous world, and these self-proclaimed wanderers came to see this vast country in a way that few Americans, and almost no black Americans, did then. Hundreds of white bigots who had never seen a black person turned out in farming villages and mining towns, and boy, what a meeting it was on both sides. Farmers and miners could hear the most intoxicating music in the world, played by passionate cornets and saxophonists, exotic trombone mutes, screeching trumpets and sensual clarinets. The musicians, meanwhile, were doing what they loved: They were treated like celebrities in ways that shaped the mold of last year's Eras and Renaissance tours.

One night in particular captured the joy Count Basie felt on tour, under circumstances that would have unsettled less determined artists. His band arrived in the lakefront town of Manitowoc, Wisconsin, the heart of Green Bay Packers country, on a night in 1972 when the Packers were facing the Detroit Lions. A television broadcast the action on the field from one end of the venue while at the other end the band sat sullenly, doubting they could compete for attention. Basie simply leaned forward and ordered, “Play.” For an hour he gave his best to the football-mad crowd and, little by little, the fans made their way across the large hall toward the music. They then called friends to join them. Near the end of the evening, the announcer borrowed the microphone to announce that the Packers had won. There was a polite applause and then someone shouted, “How about 'April in Paris' again?” Basie smiled and whispered, “Landing.”

Among African Americans, only the Pullman porters saw more of the United States, and even they simply passed through places like Fargo, North Dakota. But Ellington stayed one winter night in 1940 to attend a concert at the Crystal Ballroom that attracted about 700 fans so that, for the price of $1.30, I could hear the orchestra play at full capacity. North Dakota's population was only 0.03% black back then, so perhaps racism was not as pervasive as in other parts of the country. There was no television to distract people from the war, there was little money for movies, and there was not much else to do in a city that celebrated its political and cultural isolation. That left jazz.

For Duke, the Count, and Satchmo, music meant movement, and their freedom to wander was more liberating than a runner bursting into the clearing.

Larry Tye is the author of “The Jazzmen: How Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Count Basie Transformed America.”