Book review

'Son'

By Al Pacino

Penguin, 370 pages, $35

If you buy books linked to on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Al Pacino grew up roaming the streets of the South Bronx with his friends, getting into any trouble that might arise. In his new memoir, “Sonny Boy,” he calls his small group “a pack of wild, pubescent wolves with malicious grins” and describes how his three best friends, Cliffy, Bruce and Petey, eventually died of heroin overdoses. Pacino would limit his junkie life to the screen, in his breakout 1971 performance in “The Panic in Needle Park.” He would be the first to tell you that he was saved by art.

Throughout this discursively moving book, a series of interconnected questions are raised: Why did I succeed when so many others did not? Why can't I just practice my craft and leave out the stardom and celebrity part?

Voted most likely to succeed in high school, he considered the insignificance: “All it meant was that a lot of people had heard of you. Who wants to be heard anyway? And, a little later: “At a certain point, dealing with fame is a self-centered problem and one should probably keep their mouth shut about it. Here I am talking about it now, so I'm starting to feel like I should keep my mouth shut too.” Fortunately, he has a lot to say moving forward.

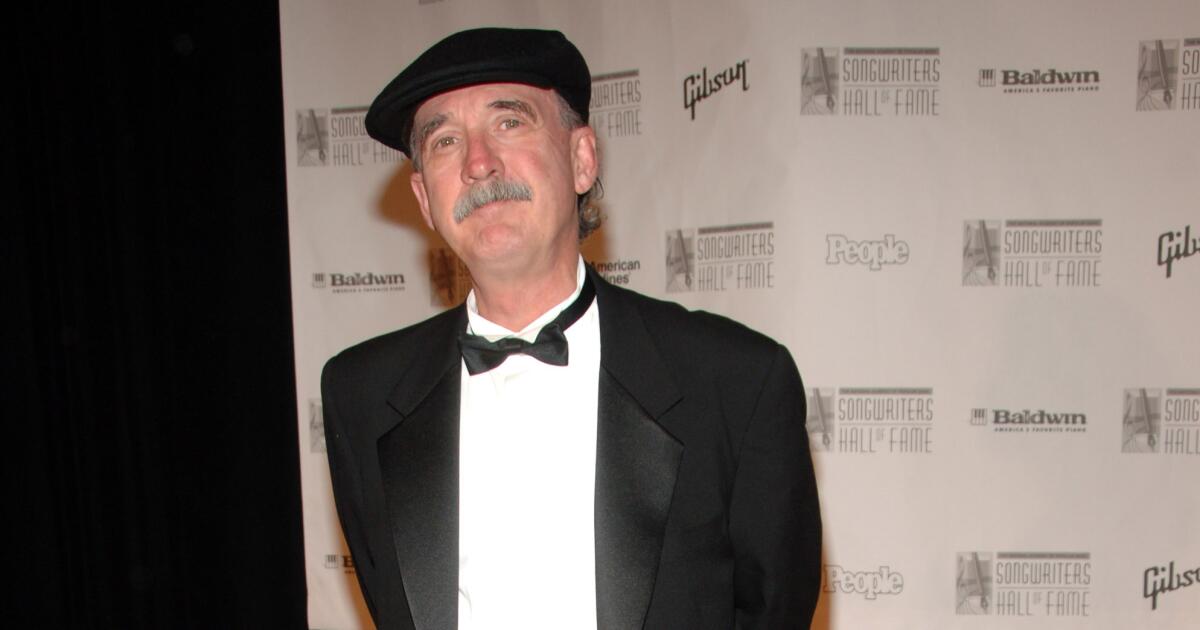

Al Pacino's new memoir, “Sonny Boy,” delves into his troubled youth, his rapid rise to Hollywood's A-list and the sometimes questionable career decisions that followed.

(Random Penguin House)

Pacino, now 84 and writing “Sonny Boy” with arts journalist and author Dave Itzkoff, doesn't really have to worry about offending the person who could get him his next job. He describes the creative disputes he had with directors, including Norman Jewison (“And Justice for All”) and Arthur Hiller (“Author! Author!”). A caption accompanying a photo of a hysterical Pacino in “Justice” reads: “I want out of this movie!”

But kissing and gossiping isn't really Pacino's craft. He presents himself as a New York stage actor fiercely devoted to the mysteries of the craft, deeply fond of poetry (and, for a long time, alcohol and drugs), and reluctant to embrace the high profile that followed the stellar success of “The Godfather” in 1972. Never too practical, he stepped away from film for a few years in the 1980s – “I began to question the very essence of what I was doing and why I was doing it” – and went bankrupt. 2011, writing: “I had fifty million dollars and then I had nothing.”

Because he's now so familiar with so many movie roles, you can almost hear him say all this in a recognizable Pacino-like tone: the upright hipster cop of “Serpico” (1973), or the slick, hungry real estate shark of “Glengarry Glen.” ”. Ross” (1992). This is part of why we gravitate toward movie stars, even those who would rather be something else. We feel like we know them. Pacino has done a lot of great work, including “The Godfather” films, “Dog Day Afternoon” (1975), “Scarface” (1983), “Sea of Love” (1989), “The Insider” (1999). and “The Irishman” (2019), that reading “Sonny Boy” often feels like diving into a history of American movies from the past 50 years.

It can also leave one wanting to know more about their particular favorites. Michael Mann’s “The Insider,” in my opinion one of the best films of the last half century, barely gets a mention. “Glengarry” also gets little attention. Come on, Al. Always be closed.

But the eccentricity of “Sonny Boy” is part of its charm, and the book's distinctive voice speaks to a fruitful collaboration between Pacino and Itzkoff, the first person Pacino thanks in his acknowledgments: “His considerable help and perseverance helped me to overcome the situation. “I would never have turned around.”

These pages contain pain, for Pacino's largely absent father and severely depressed mother, for his deceased childhood friends, for the poverty and uncertainty that marked his youth. There's also the jolt of discovery, like when a theater group arrived at 15-year-old Pacino's favorite movie theater to perform Chekhov's “The Seagull” and lit a fire under him. “Chekhov became a friend of mine,” writes Pacino, known for wandering the streets of New York reciting his favorite theatrical monologues at the top of his lungs.

Reflecting on the fate of his friends who died from the needle, he asks, “Why didn't I end up like this? Why am I still here? Was it all luck? Was it Chekhov? Was it Shakespeare? He almost answers the question elsewhere, when he considers aspiring actors who ask why he made it and they didn't: “You wanted to. I had to do it.”

If talking about the industry is your thing, Pacino tries to please you. He writes that he recently heard an old rumor that he didn't attend the Oscars in 1973 because he was nominated for supporting actor instead of leading actor for “The Godfather.” He offers a much simpler explanation: He was terrified. “That goes a long way toward explaining the distance I felt when I came to Hollywood to visit and work,” he writes. It might also help explain why he didn't win his first (and only) Oscar until 1993 for “Scent of a Woman,” in which he gave a performance that was nowhere near his best performance. (He has been nominated nine times.) He talks about his various Hollywood romances, including Jill Clayburgh, Tuesday Weld, Diane Keaton and Marthe Keller. Pacino, by his own admission, is an obsessive workaholic, a habit that hasn't done him many favors off screen and stage. He appears to be a devoted father to his three children.

“Theater people are vagabonds, wandering gypsies,” he writes. “We are people on the run.” And despite his movie stardom, Pacino makes it clear that, at heart, he is a theater person. The two-time Tony Award winner is an artist who has the career of a celebrity. He convincingly presents himself as an outsider who crashed the party, driven by work above all. Is this a self-interested representation? Maybe. But most celebrity memoirs are. At least “Sonny Boy” is also rife with what certainly feels like a self-deprecating honesty to go with Pacino's well-worn swagger.