The American Heart Association. He calls them “game changers.”

Oprah Winfrey says they are “a gift.”

Science magazine named them “Breakthrough of the Year 2023.”

Americans are more familiar with their brands: Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro, Zepbound. They are the medications that have revolutionized weight loss and have raised the possibility of reversing the country's obesity crisis.

Obesity, like so many diseases, disproportionately affects people from racial and ethnic groups that have been marginalized by the American healthcare system. A class of drugs that succeeds where many others have failed would appear to be a powerful tool to close the gap.

Instead, doctors who treat obesity and the serious health risks it brings fear that medications are worsening this health disparity.

“These patients have a higher burden of disease and are less likely to receive life-saving medication,” said Dr. Lauren Eberly, a cardiologist and health services researcher at the University of Pennsylvania. “I feel like if one group of patients is disproportionately burdened, they should have done it. increase access to these medications.”

Why do not they do it? Experts say there are a multitude of reasons, but the main one is cost.

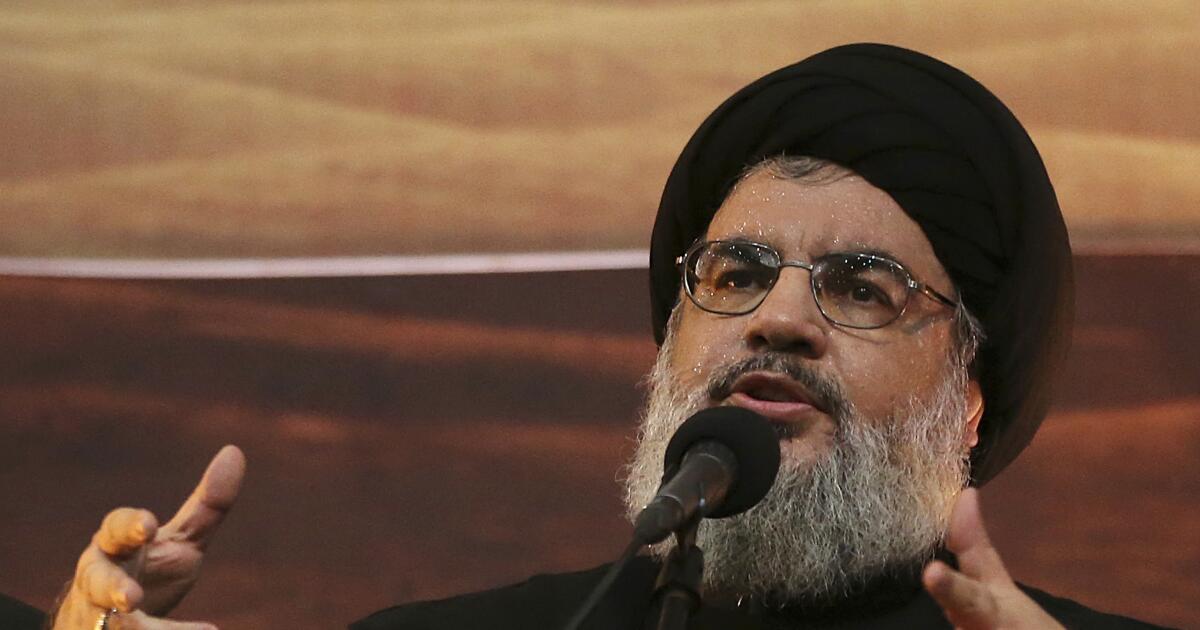

The injectable drug Ozempic sparked a revolution in obesity care.

(David J. Phillip/Associated Press)

Ozempic, which is approved by the Food and Drug Administration to help people with type 2 diabetes control their blood sugar and reduce the risk of serious cardiovascular problems such as heart attacks and strokes, has a list price $968.52 for a 28-day supply. Wegovy, a higher dose of the same drug approved by the FDA for weight loss in people who are obese or overweight and have a weight-related condition such as high blood pressure or high cholesterol, costs $1,349.02 every four weeks.

Mounjaro is a similar medication approved by the FDA to improve blood sugar levels in patients with type 2 diabetes, and has a list price of $1,069.08 for 28 days of medication. Zepbound, a version of the same drug approved for weight loss, is priced slightly lower at $1,059.87 for 28 days. At least for now, all new medications must be taken indefinitely.

Few health insurance programs cover prescription medications to help people reach and maintain a healthy weight. Federal law requires that weight-loss drugs be excluded from basic coverage in Medicare Part D plans, and as of early 2023, only 10 states included an anti-obesity drug on their Medicaid program formularies. .

“If everyone had equal access, then this would be a way to help,” said Dr. Rocío Pereira, chief of endocrinology at Denver Health. “But without equitable access, which is what we have now, this is likely to increase the disparity we see.”

Obesity rates in the United States have been rising for decades and are consistently higher for black and Latino Americans. Among adults ages 20 and older, 49.9% of African Americans and 45.6% of Hispanic Americans have a body mass index of 30 or higher, compared to 41.1% of white American adults and 16.1% of Asian American adults, according to age-adjusted data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Obesity rates are also associated with income. In 2022, the age-adjusted rate was 38.4% for adults with household incomes between $15,000 and $24,999, compared to 34.1% for those with household incomes of $75,000 or more.

The two are related, said Pereira, who studies health disparities in obesity-related diseases. Black and Latino Americans are more likely to live in low-income neighborhoods, where fast food is often cheaper and more convenient than grocery stores.

“If you look at a map of the United States and plot the neighborhoods where there are no grocery stores within a mile radius and there is a high percentage of people who don't have cars, those are the areas where there are the highest rates of obesity,” said. .

There's also the time factor, he said: “Can you afford to cook your own meals or do you have to work two jobs?”

An unusual experiment conducted by the Department of Housing and Urban Development demonstrated the extent to which the physical environment can influence obesity risk, Pereira said. In the 1990s, hundreds of mothers living in public housing were offered housing vouchers that they could only use in wealthier neighborhoods. Ten to 15 years later, women randomly assigned to receive the windfall money had significantly lower rates of severe obesity (14.4%) than women in a control group who were not offered vouchers (17.7). %). They were also less likely to have a body mass index of 35 or higher (31.1% vs. 35.5%).

Two women talk in New York.

(Mark Lennihan/Associated Press)

The American Medical Association. recognized obesity as a disease in 2013. People with this chronic disease have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, 13 types of cancer, osteoarthritis, asthma and other health problems. Researchers have estimated the annual medical costs associated with obesity at $174 billion in the United States alone.

Some people with obesity can lose weight by changing their diet and burning more calories through exercise. But that doesn't work for people who have developed resistance to leptin, a hormone that suppresses appetite.

“If you try to lose weight with diet and exercise, your body will fight with you,” said Dr. Caroline Apovian, co-director of the Center for Weight Management and Wellness at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston. “Your leptin levels go down, and when leptin goes down, a signal goes to the brain that you don't have enough fat to survive.” This causes the release of another hormone, ghrelin, which causes the feeling of hunger.

Leptin resistance also makes exercise less valuable.

“Your body fights against you by decreasing your total energy expenditure,” Apovian said. “When your muscles work, they work more efficiently. If you want to lose 10 pounds, you will be very, very hungry. And you can't fight that. Your body thinks it’s starving.”

“Innovative” drugs counter this by mimicking a hormone called glucagon-like peptide 1, or GLP-1, which is involved in regulating appetite. Inside cells, the drugs bind to the same receptors as GLP-1, lowering blood sugar and slowing digestion. They also last longer than their natural counterparts.

Oprah Winfrey credits the new generation of medications for helping her keep her weight under control.

(Chris Pizzello/Associated Press)

The first GLP-1 receptor agonist was approved in 2005 to treat diabetes, and early versions needed to be injected once or twice a day. Ozempic improved this by requiring an injection only once a week. After clinical trials showed that the drug helped people with obesity achieve substantial and sustainable weight loss, the FDA approved Wegovy as a weight management drug in 2021.

Mounjaro and Zepbound also mimic GLP-1, along with a related hormone called glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide, or GIP.

Linda Morales credits Ozempic and Mounjaro with helping her lose 100 pounds and go from a size 22 to a size 14. The 25-year-old instructional assistant at Lankershim Elementary School in North Hollywood said she started becoming overweight in school high school and weighed 293 pounds. She weighed pounds on her 5-foot-5-inch frame when she was referred to the Cedars-Sinai Center for Weight Management and Metabolic Health two years ago.

He no longer gets out of breath when climbing stairs, finds it easier to bowl, and fits comfortably in the seat of the Harry Potter ride at Universal Studios. Thanks to medication, he is no longer on the path to type 2 diabetes.

Her job at the Los Angeles Unified School District includes health insurance that covers expensive medications and charges her a $30 copay a month for her Mounjaro prescription. He said he could make a monthly payment of up to $50, but beyond that he would have to stop taking the medication and hope that the lifestyle changes he had made were enough to maintain the weight loss he had achieved so far.

“It would definitely be difficult for me, for sure,” Morales said.

In fact, even when medications are covered by insurance or patients qualify for discounts from pharmaceutical companies, researchers have found that they often remain out of reach.

In one study, Eberly and his colleagues examined the insurance claims of nearly 40,000 people who received a prescription for GLP-1 mimics. Patients who had to pay at least $50 a month to fill their prescriptions were 53% less likely to get most of their refills over the course of a year compared to patients whose co-pays were less than $10. Even patients whose out-of-pocket costs ranged from $10 to $50 were 38 percent less likely to purchase the drug regularly for a full year, the team found.

In another study of insured patients with type 2 diabetes, blacks were 19 percent less likely to be treated with these medications than whites, while Latino patients were 9 percent less likely to receive them, Eberly and his colleagues.

In some parts of the country, black patients with diabetes are only half as likely as white patients to receive GLP-1 medications, according to research by Dr. Serena Jigchuan Guo of the University of Florida, who studies disparities in diabetes. health in access to medicines. The disparity was greatest in places with the highest overall use of the drugs, including New York, Silicon Valley and South Florida.

“In those places, the drug is actually widening the gap,” he said.

Researchers have been documenting racial disparities in the use of effective obesity treatments, such as bariatric surgery, for years. Newer drugs like Ozempic simply put more focus on the problem, said Dr. Hamlet Gasoyan, a researcher at the Cleveland Clinic's Value-Based Care Research Center.

“We get excited every time a new, effective treatment comes out,” Gasoyan said. “But we should be equally concerned that this new, effective treatment will reduce disparities between the haves and have-nots.”