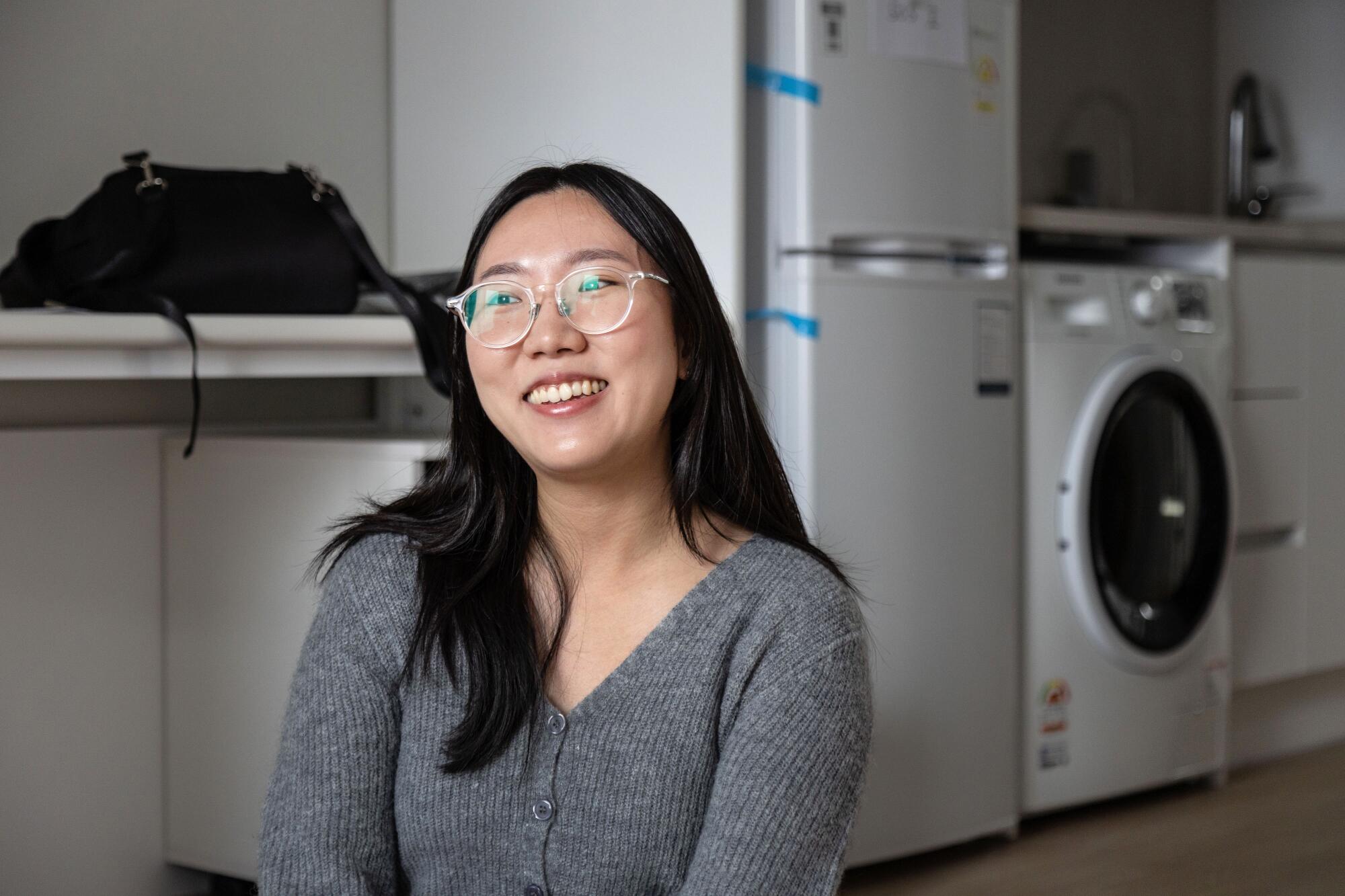

The studio apartment Choi Soul recently obtained might have the cheapest monthly rent in Seoul: 10,000 won, or about $7.

“After I received the text informing me that I had received it, I looked at it over and over again for a week straight,” said the 24-year-old college student. “I felt like I could finally start saving for my future.”

The new unit is compact (226 square feet) but comes equipped with air conditioning, induction cooktop, refrigerator, washing machine, and plenty of cabinet space.

Choi Soul in his room inside the $7 youth apartment in Seoul's Dongjak district.

Choi, who moved in last week, only had to ask for a bed.

Part of a new public housing complex in Seoul's Dongjak district called Yangnyeong Youth House, the heavily subsidized studio was built for people like her: young South Koreans struggling to find a place to live.

Seoul, home to 10 million people, has one of the most expensive real estate markets in the world. The average price of an apartment has doubled in the last 10 years to about $685,000.

Buying a home here is often known as “gathering your soul.”

“I don't think anyone my age can buy a house here,” Choi said. “Maybe it will be easier for the next generation.”

The rental situation hasn't been much better.

In December, the average monthly rent for apartments in Seoul under 355 square feet was $457, up 15% from 2021, according to government data analyzed by housing advocacy group Minsnail Union.

In some college neighborhoods, single-person units now cost up to $700.

For Choi, who earns the national minimum wage of $7 an hour as a freelance cameraman while studying broadcast journalism, seeing these prices is like “being trapped at the first gates of adulthood.”

In addition to real estate speculation, recent changes in rental preferences and the country's demographics are to blame for the housing crisis.

Until recently, most middle-class South Koreans rented their homes through a unique system called jeonse. Instead of paying a monthly rent, the tenant pays the landlord a deposit of up to 70% of the market value of the property.

For a long time it was a win-win proposition.

Interest payments on jeonse Loans are generally lower than rent would be, allowing tenants to more easily save for their own homes. For homeowners, lump sum deposits effectively act as interest-free loans, which they can use to invest in stocks or real estate.

But a series of high-profile scams, in which over-leveraged landlords refused to return deposits, has increasingly driven tenants away from jeonse and towards paying rent in cash, an option that used to be mainly for the young or the poor.

South Koreans are also taking longer to get married or start a family, further increasing demand in the cash rental market, where most single-person homes can be found.

“Competition is very high right now and will probably get worse,” said Seo Won-seok, a real estate policy expert at Chung-Ang University. “What this also says is that we need more public housing to alleviate these trends.”

Seoul is still home to a fifth of the country's population, but housing problems are the main reason why 1.7 million South Koreans have left the capital for surrounding provinces in the last decade, swapping cheaper rents for travel. longer to the city center.

In a climate like this, getting a place in public apartments like Yangnyeong is like winning the lottery.

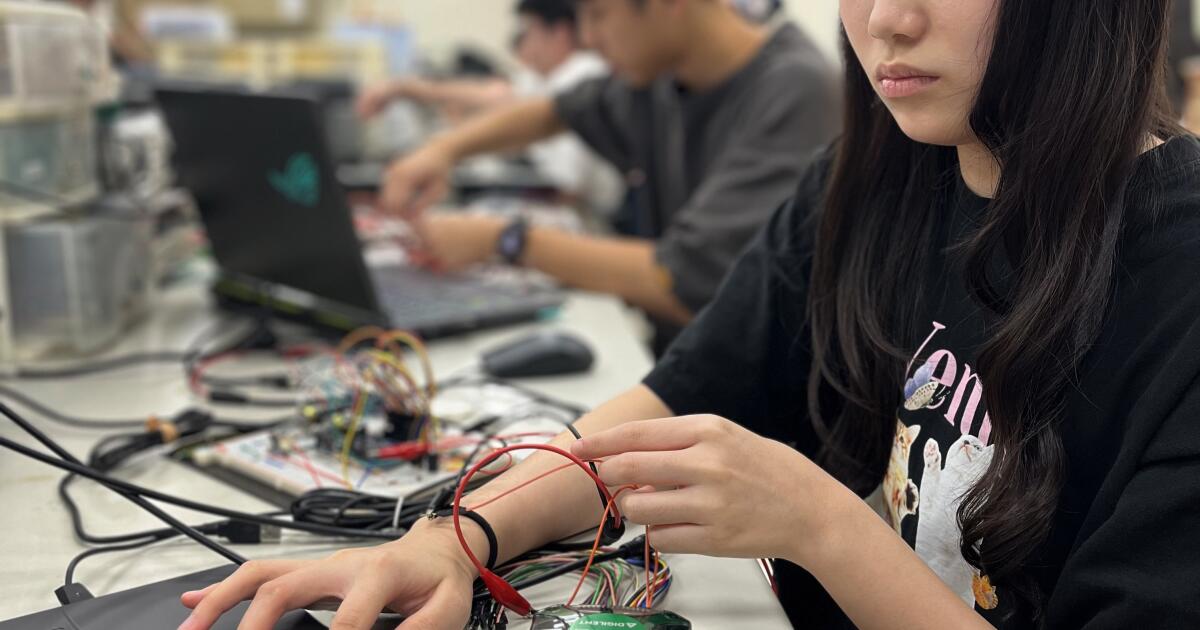

“Everyone around me wants to enter a public apartment,” said Kim Do-yeon, a 25-year-old college student who works part-time as a convenience store clerk. “I applied for five other places before I got this one.”

Kim Do-yeon talks about how she feels about her room at the $7 youth apartment in Seoul's Dongjak district.

Kim was among 700 people who applied for one of the 36 units of the Yangnyeong Youth House, which the district built on a public parking lot.

Only those between 19 and 39 years old, with a monthly income of $1,620 or less were eligible for a spot.

On paper, the monthly rent is $93, low even by public housing standards. But using profits from its public works corporation, the district is offering $7 rents for the inaugural group of tenants.

“For now, we have secured enough funds for the first six months, but we plan to continue offering the same rate even after that,” said Choi Sun-young, spokesperson for the district office.

“We are also currently developing additional $7 public rentals for other young renters, such as newlywed couples.”

Still, it's not as cheap as it seems: Each tenant must pay a security deposit of about $10,000.

Kim received help from her parents, who were already helping her with basic expenses. The small apartment he leaves her, with a single window that faces a concrete wall, cost him $446 a month.

After signing his contract with a district official, Kim headed to the fifth floor to tour his new place, which smelled like a new house and was filled with sunlight.

“Wow, it's so spacious,” he said.

“You can put blinds or curtains here,” explained the official, standing next to the window. “But please don't put nails in the walls.”

Kim didn't care.

“I can't even cook in my current place because there is not enough space and the ventilation is very bad,” he said. “Now I can finally cook my own meals.”

Kim Do-yeon opens her bedroom window in her cheap new apartment.

Tenants have the option to renew their two-year lease four times, meaning this will be the home that will keep Kim well into her 30s.

By then, she hopes to have settled into a career as an accountant.

But after that, he said, his time in Seoul will end.