Elections in other countries don't typically disrupt daily life in the United States, but the vote that Venezuela's authoritarian government plans to hold on Sunday is an exception. It is likely to have implications for immigration to the United States, the U.S.-Mexico border and perhaps even the race for the White House.

If Venezuela’s socialist president, Nicolás Maduro, wins another term — which, given his opponent’s 25- to 30-point lead in the polls, would require massive fraud — even more Venezuelans will flee their country and its collapsing economy, joining the nearly 8 million already abroad. A recent poll suggested that more than 10% of the country’s population would try to emigrate if Maduro retains power. Many will head to the United States, possibly reinforcing Donald Trump’s claims of an out-of-control border and dimming Democrats’ prospects.

But if opposition candidate Edmundo González Urrutia wins in a landslide, as polls predict, and if, against all odds, a critical mass of members of Maduro's government recognize him, Venezuela could be ready to turn toward greater stability, more democracy and less emigration.

That's what Maria Corina Machado, the charismatic opposition leader, has promised as she tours the country rallying voters around Gonzalez (Machado herself would be on the ballot had the government not banned her from running).

While Machado promises that elections can bring change—and many Venezuelans are eager to believe him—there's no ignoring the obvious: Maduro, with charges from the U.S. Justice Department, a bounty from the U.S. State Department, and a International Criminal Court Investigation The president, who faces the threat of extrajudicial killings and torture, has every incentive to fight to stay in power, regardless of the results. Many expect him to manipulate the election as he has done before and use the military to crush any post-election protests.

His government has already targeted numerous people linked to Machado, from his top bodyguard To the sellers who sold it empanadas. On Thursday, he accused government agents of cutting the brakes on his car.

But Venezuelans are not waiting in vain for change. Authoritarians sometimes lose control of elections, even those they try to plan in advance. In the Philippines, Chile, Nicaragua and, most recently, Guatemala and Honduras, autocrats have confidently entered elections they thought they could control but have found they could not. Landslide opposition victories were too large to erase with fraud, attempts to deny the results sparked mass protests or members of the government and military defected, leaving autocrats isolated.

The chances of such a scenario occurring in Venezuela, while low, are not zero. What could force Maduro to accept defeat? Three factors have played a role in other countries and are likely to play a role in Venezuela as well: the military, the voters and other countries in the region.

For an autocrat, the support of military generals is the ultimate backer. With the gun guys on your side, you can resist almost any amount of popular pressure. In this regard, Maduro seems to have his bases covered: he controls the military with a system of incentives and punishments. Incentives include military control of key sectors of the economy and organized crime. The sticks are kidnapping and torture of those suspected of disloyalty by Venezuelans and Cubans counterintelligence agents.

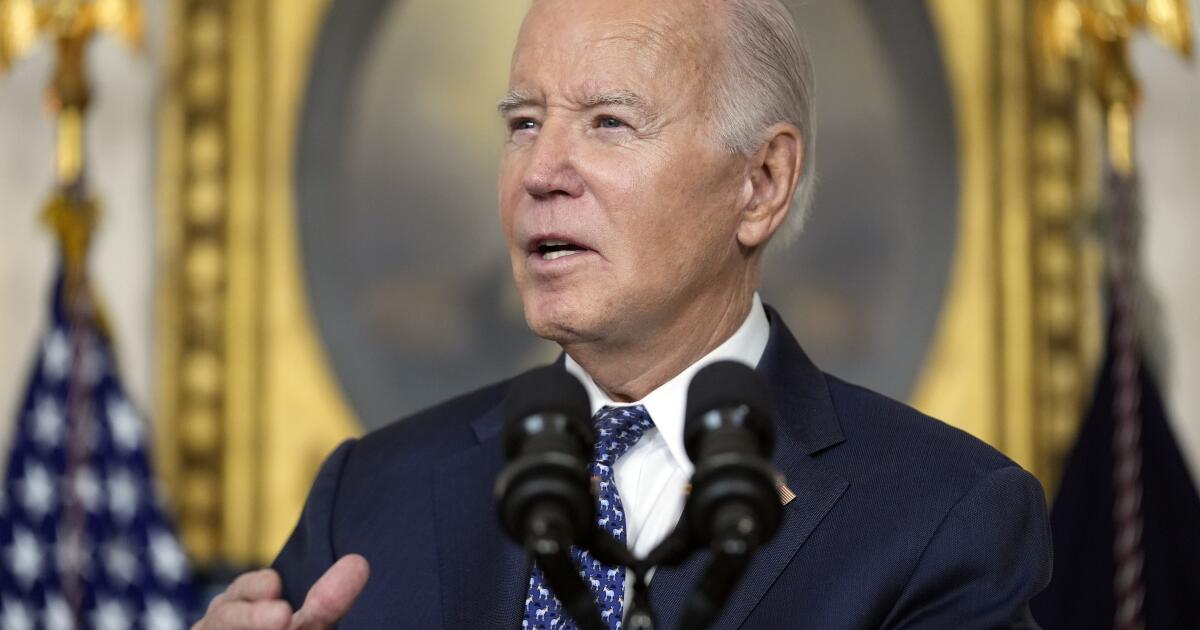

If the military abandons Maduro after the vote — which is not entirely clear — it will be because the carrots have run out and the opposition has promised protection from prosecution. The middle ranks of the armed forces — who are more likely to experience the deprivation of daily life in Venezuela than to share in the generals’ spoils — are already disaffected, according to one leading expert. And between the Biden administration’s renewed sanctions on Venezuelan oil and Maduro’s spending to get out votes, the president may be running out of money to line the generals’ pockets. Some see signs of weakness in the security forces’ relative restraint in countering some recent opposition demonstrations.

The country's electorate is another key factor. For years, opposition infighting led to voter apathy. But today the opposition is united and organized like never before, energizing voters, nearly half of whom told pollsters they would protest if there is electoral fraud.

Make no mistake: these elections will not be free or fair. The Maduro government has dominated Voter suppression and manipulation.

But margins matter, and Maduro has rarely fallen so far behind his rivals in the polls. Erasing a 5- or 10-point loss with fraud is one thing; a 30-point loss is another. Moreover, the opposition is willing to conduct exit polls and document irregularities. A similar effort allowed the Honduran opposition to demonstrate its landslide victory in 2021 and pressure the ruling party to acknowledge defeat. The larger and more irrefutable the victory, the greater the chances that Maduro will lose control.

The third crucial variable is Venezuela’s neighbors (or, rather, its neighborhood): Latin America and the United States. Regional powers have facilitated other democratic transitions by combining pressure on authoritarians with assurances that they will not lose everything (including their freedom) if they leave power.

In this case, things are more complicated. Maduro and his inner circle are accustomed to economic sanctions and other forms of pressure from the United States. They likely fear a further tightening of sanctions by President Biden, who wisely refrained from fully reimposing them to preserve his influence, but they fear losing power even more. And Maduro is unlikely to rely on many other governments to guarantee him a soft landing if he steps down. The leftist presidents of Colombia and Brazil, who have oscillated between criticizing and apologizing for Maduro, are unlikely to publicly pressure Maduro to relent, but they could mediate negotiations between the government and the opposition in the event of a disputed election.

If the unlikely happens on Sunday and the outcome turns out to be a serious threat to the regime, that will be just the beginning. Negotiations over power-sharing and a soft landing for Maduro could follow. The U.S. embassy in Caracas could eventually reopen and begin working with the Venezuelan government to address the economic chaos and mass migration it creates.

But if the expected happens and Maduro clings to power through fraud and other illegitimate means, Venezuela will have lost perhaps its last great opportunity for change for a long time. Instability will persist and perhaps deepen, and Latin America and the United States will have no choice but to accept the consequences.

Will Freeman is a fellow in Latin American studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.