The use of the military to suffocate protests is something associated with dictators in foreign countries, and until Saturday night, with a president of the United States. When President Trump federalized 2,000 members of the California National Guard, deploying them due to protests against federal immigration authorities, he sent a chilling signal about his willingness to use the military against protesters.

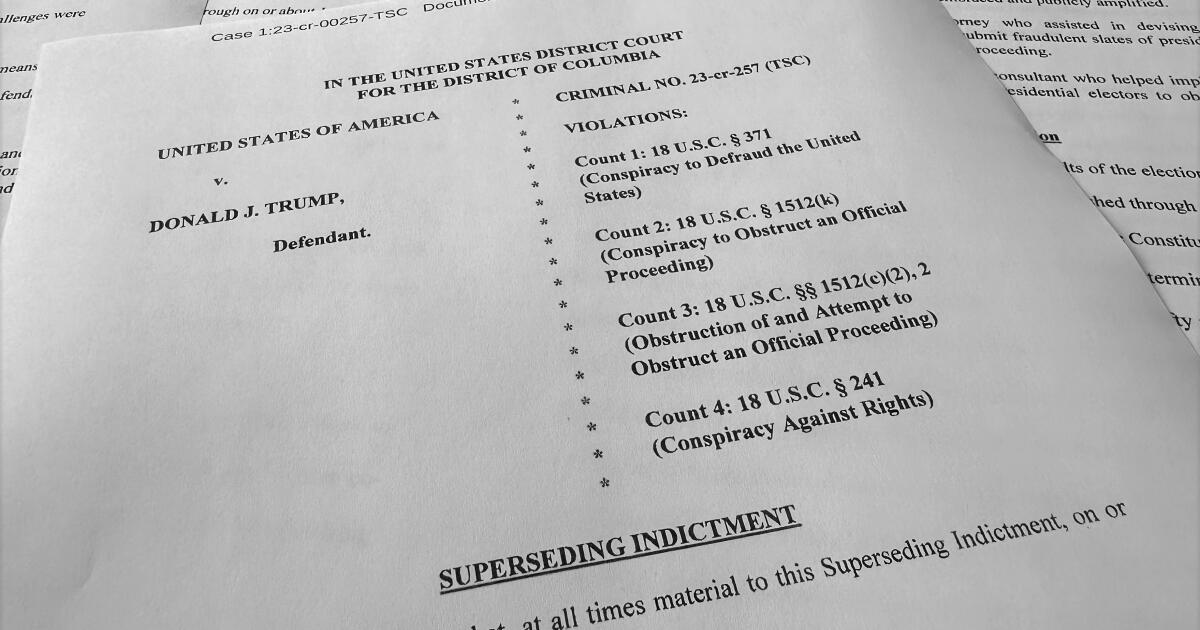

There are two relevant aspects of the Federal Law: one allows the president to federalize the National Guard of one State and the other allows the president to use the military in national situations. Neither of them, at this point, provides legal authority for Saturday's action.

As for the first, a Federal Statute, 10 of section 12406 of the USC, authorizes the President to take care of the National Guard of a State if “the United States, or any of the Commonwealths or possessions, is invaded or is in danger of invasion by a foreign nation; there is a resignation or danger of a rebellion of a rebellion of the United States.

This is the legal disposition that Trump has invoked. But it is very questionable that protests against ice agents rise to the level of a “rebellion against the authority of the government.”

This statute does not give the president the authority to wear The troops. Another law, the POSSE Comitatus Law, usually prohibits the military from being used within the United States. The 2,000 National Guard troops only display protect Ice officers. However, even this is legally questionable unless the President invokes the insurrection law of 1807, which creates a basis for using the military in domestic situations and an exception to the POSSE Commitatus Law. On Sunday, Trump said he was considering invoking the insurrection law.

The insurrection law allows a president to deploy troops nationwide in three situations. One is whether a state governor or legislature requests that the deployment leave an insurrection. The last time this happened was in 1992, when the governor of California, Pete Wilson, asked President George Hw Bush to use the National Guard to stop the disturbances that occurred after police officers were acquitted by Rodney King's beating. With Governor Gavin Newsom opposes the federalization of the National Guard, this is not the case in Los Angeles today.

A second part of the insurrection law allows deployment to “enforce the laws” of the United States or “suppress the rebellion” provided that “illegal obstructions, combinations or assemblies or rebellion” make it “impracticable” to enforce the federal law by the “ordinary course of judicial procedures.” As nobody disputes, the courts are working completely, this provision has no relevance.

It is the third part of the insurrection law that is most likely to be cited by the Trump administration. It allows the president to use military troops in a state to suppress “any insurrection, domestic violence, illegal combination or conspiracy” that “this hinders the execution of laws” that any part of the inhabitants of the State are deprived of a constitutional right and the state authorities cannot or do not want to protect that right. President Eisenhower used this power to send federal troops to help disaggregate the public schools of Little Rock, Arkansas, when the governor challenged the orders of the Federal Court.

This section of the law has an additional language: the President can display troops in a State that “opposes or obstructs the execution of the laws of the United States or prevents the course of justice under those laws.” This broad language is what would expect Trump to invoke to use troops directly against anti-hell protests.

The insurrection law does not define crucial terms such as “insurrection”, “rebellion” or “domestic violence.” In 1827, in Martin vs. Mott, the Supreme Court said that “the authority to decide if [an exigency requiring the militia to be called out] It has emerged belongs exclusively to the president, and … his decision is conclusive over all other people. “

There have been many calls over the years to modify the expansive language of the insurrection law. But since the presidents have rarely used it, and not in much time, reform efforts seemed unnecessary. The wide presidential authority under the insurrection law has remained in books as a loaded weapon.

There is a strong set of norms that has prevented presidents from using federal troops in national situations, especially in the absence of a request for a state governor. But Trump does not show respect for the rules.

Any use of the military in domestic situations should be considered as a last resort in the United States. The preparation of the administration to quickly invoke any aspect of this authority is terrifying, a message on the will of a federal reception to quell the demonstrations.

The protests in Los Angeles do not rise to the conditions that justify the federalization of the National Guard. This is not to deny that some of the anti-there protests have become violent. However, they have been limited in size and there is no reason to believe that the police could not control them absent from the military force.

But Trump statutes can invoke presidents broad powers. In the context of everything we have seen in the Trump administration, nationalize the California National Guard should make us even more fear.

Erwin Chemendnsky, dean of the UC Berkeley Law Faculty, is an opinion writer.