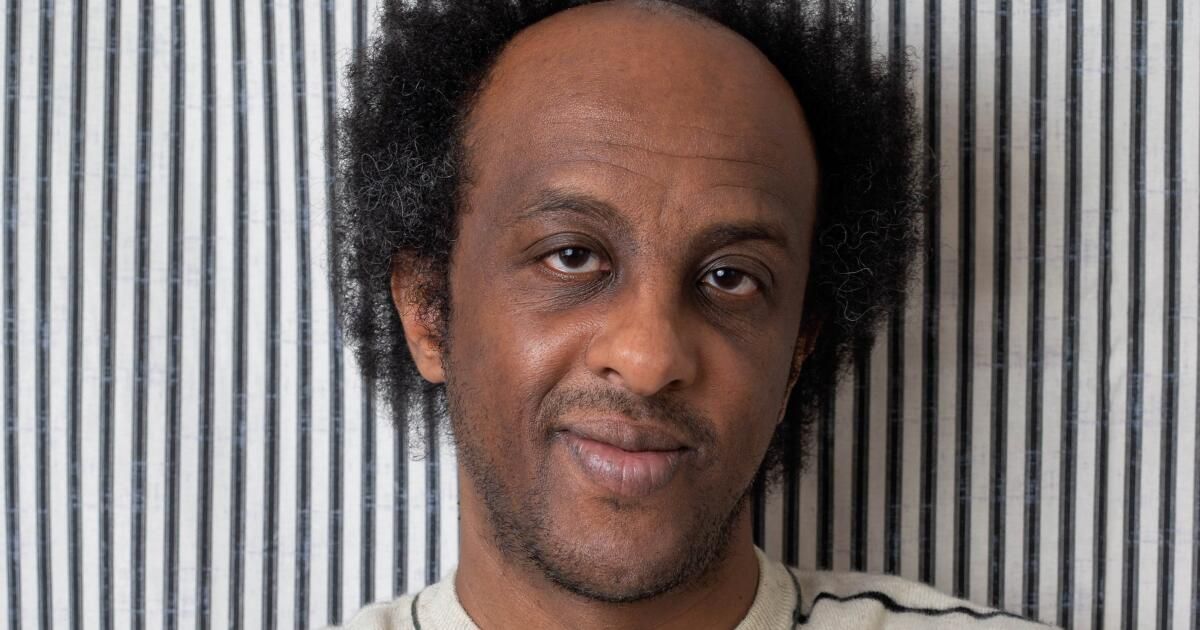

Book Review

Someone like us

By: Dinaw Mengestu

Knopf: 272 pages, $28

If you purchase books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Across four excellent novels, Dinaw Mengestu has challenged conventional wisdom about how immigrant narratives should work. It’s not just that he’s skeptical of pat stories about trauma and assimilation into American life, but that he strives to use language to reveal the instability at the heart of the lives of exiles, émigrés, and refugees without falsely promising an easy resolution.

His exploration of slippery identities in a complicated America earned him a MacArthur “genius” fellowship in 2012, giving him access as a journalist covering Darfur and other troubled regions around the world. But in “Someone Like Us,” his first novel in a decade, Mengestu subjects that kind of achievement to the same level of scrutiny and skepticism. Mamush, the novel’s narrator, is an Ethiopian-American writer who specializes in journalism about immigrant lives. A family friend is unimpressed: “You write stories for people who want to feel bad for immigrants.”

At the beginning of the story, Mamush is mourning the death of Samuel, whom he calls his father two pages later. But Mamush's mother has never confirmed Samuel's paternity, only that she met him in Ethiopia.

“Someone Like Us” by Dinaw Mengestu.

(Knob)

Upon learning that Samuel was gravely ill (we don’t know from what), Mamush hurriedly abandoned his family in Paris and flew to the suburbs of Washington, D.C., where he grew up. Then, to unravel the mystery of his origins, he went to Chicago, where his mother and Samuel first settled. He inherited stories about Samuel’s run-ins with racist police officers and that he “spent some time in prison, but I don’t know why.” Mamush hoped his journalistic skills might uncover the truth, but he found nothing in the courthouse: the arrest records are sealed, and while he was searching, Samuel died.

All of that information is carefully distributed throughout Mamush’s narrative, which oscillates between true chronicle and imagined realities, each flowing sinuously from one to the other. Mamush lives in a world where things seem to be constantly in limbo. Hannah, his wife, is a photographer assigned to photograph “semi-ruins… buildings that haven’t collapsed but probably will soon.” As Mamush waits in line at the courthouse on a frigid Chicago day, a woman offers him a scarf, but he “wanted to tell her that I didn’t need protection from the cold, that what she saw was a shadow version of me; the real me was hundreds of miles away in the suburbs of Northern Virginia.”

The crack in a clear reality is most pronounced when it comes to Samuel. “Today you say you are like a father to me,” Mamush once tells him. “But maybe tomorrow you will be like a distant cousin whom I have only met twice. Similes can change. They can be revised, edited.” His understanding of Samuel is made up of scraps of memories and documents, but he belongs to a family that disdains memory. When at university he asked his mother for help writing an essay about childhood memories, she sardonically asked if she could get a tuition refund.

How, then, does one write a story about fathers and sons when fatherhood is questioned or nonexistent and all the stories that could be told would seem the most trite and obvious? Throughout “Someone Like Us,” one can sense Mengestu’s determination to avoid falling into familiar immigrant narrative tropes. Samuel’s experience with racism is maddening but far from cataclysmic; Mamush shares little about his family’s past in war-torn Ethiopia, and even less about Samuel’s time in prison. For him, it’s impossible to write straightforward reportage: Mamush irritably recalls an editor who sent back a story, saying that what he had sent had “nothing to do with the story I was supposed to write. Where’s the portrait? What’s the conflict? And why should people care?”

The kind of anti-characterization Mengestu plays with here is risky. Rather than simply feeling dissociated, Mamush seeks out a lack of distinctive features. (“You’re like a doughnut,” a friend tells him. “There’s a hole in the middle, where there should be something solid.”) Rather than becoming a tragic, mysterious father figure, Samuel might end up being simply a bundle of confusions that resist interpretation: Schrödinger’s father.

But Mengestu’s solution is ingenious: he turns the drive to create a coherent story into a kind of character in itself, revealing how desperate we are to invent narratives out of scattered fragments. In the final chapters, Mengestu invents a kind of fantasy out of this instinct, constructing an imaginary story about Samuel from the available evidence, shaped by Mamush’s own uncertain yearnings.

In the process, Mengestu manages to do both: he tells a story about immigrants and critiques it at the same time. He encapsulates the feelings of loss and detachment that Mamush grapples with, while also acknowledging that there is no clear path from point A to point B. In that sense, he is his father’s son: Mamush is a traveling journalist and Samuel was a taxi driver. Quietly moving, this novel captures the uncertainty that comes with homelessness and rootlessness.

At one point, Mamush describes his ambition to write a story “about a group of people in one place at one time, who move to another place at another time for a hundred different reasons that we can never explain and can never fully understand… There is no plot.” It seems like an impossible task, but in Mengestu’s hands, plotlessness and incomprehension never seemed so essential to getting the story right.

Mark Athitakis is a Phoenix writer and author of “The New Midwest.”