Tom Girardi had a relationship of trust with senators from California to North Carolina.

The governor was on speed dial, and legions of state and local officials lined up to attend his boozy parties in Beverly Hills, Las Vegas and elsewhere.

Yet few places did the once-legendary plaintiff's attorney wield as much power as in the courtrooms of downtown Los Angeles, where he swayed juries with his honey-smooth voice and countless judges attributed their bench appointments — at least in part — to Girardi's blessing.

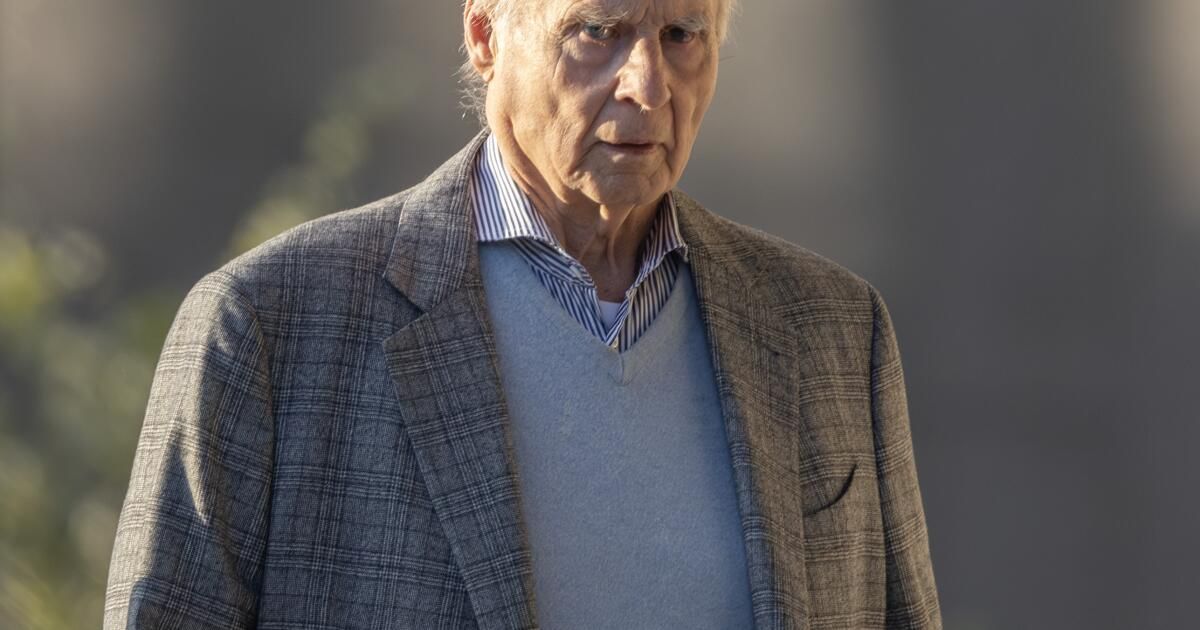

On Tuesday, one of those downtown federal courthouses was the scene of the latest low point in Girardi's long descent from legal titan to disgraced and bankrupt former attorney, as jurors were sworn in and his criminal trial began.

Girardi is charged with four counts of wire fraud for allegedly looting $15 million from clients over a decade.

As the 85-year-old sat calmly in a blue sweater and gray plaid jacket next to his defense team, Assistant U.S. Attorney Scott Paetty said Girardi “lied to his clients, stole from them, violated their trust and broke the law.”

All of those clients had come to him in times of tragedy — a burn victim, a widow whose husband died in a tragic boating accident, a woman injured by a medical device and another woman injured in a car accident — and he secured settlements from them. The prosecutor said the problem stemmed from the way he handled the money.

“By lying and stealing millions and millions of dollars from his settlement, the defendant repeatedly singled himself out,” Paetty said.

“That money did not belong to the defendant,” he said. “It belonged to the victims’ clients and was to be promptly paid to the victims’ clients.” The prosecutor tensely detailed how money belonging to a lawyer’s client must remain locked away in a special bank account.

“He treated that client trust account like it was his personal piggy bank,” Paetty said.

Two private jets, jewelry, country club memberships, a mansion in Pasadena and a home in Palm Springs. Paetty said the funds he pocketed from clients funded an exorbitant lifestyle and that another $20 million from the company’s bank account went toward the show-business career of his now ex-wife, “Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” star Erika Girardi.

But Girardi’s defense team dismissed the prosecutor’s account as a Hollywood fiction plot that incorrectly cast their client as the villain. Samuel Cross, an assistant federal public defender, invited the five women and seven men on the jury to see Girardi as a once-powerful lawyer whose later years were marred by progressive dementia, disorganization at his law firm, Girardi Keese, and large-scale theft by the firm’s chief financial officer, Christopher Kamon.

In essence, it was Girardi who was defrauded, Cross said.

Kamon quietly pocketed more than $50 million from his boss through a variety of transactions: checks to fake companies, payments to friendly suppliers and $23 million in charges to American Express cards, the defense attorney said.

As a result, Girardi had to invest $80 million of his own money into Girardi Keese.

“He’s trying to keep this company afloat,” Cross told jurors. “Why is the company going under? Because Chris Kamon is stealing money.”

Cross repeatedly returned to the complexity of the law firm's operations between 2010 and 2020, the period at the heart of the case.

At that time, more than $1 billion flowed through Girardi Keese in 300,000 transactions in 175 bank accounts. As the person overseeing the books, Kamon had unique power to gradually divert the money to pay his girlfriend $20,000 a month and buy homes in Los Angeles and, later, the Bahamas.

“This boring detail is how Chris Kamon makes the robbery happen,” Cross added.

Prosecutors have also charged Kamon with wire fraud and separately accused him of participating in a “parallel fraud” in which he siphoned off millions of dollars from the company. Kamon has pleaded not guilty in both cases and is scheduled to go to trial next year. Both men face another trial in 2025 in Chicago on charges that they stole payments made by Boeing to families whose loved ones died in a plane crash in Indonesia.

Prosecutors had long expected Girardi to blame Kamon.

In his opening statement, Paetty told jurors that the amount allegedly stolen by Kamon was “a fraction” of the amount Girardi is accused of taking and that, regardless, it was Girardi, not Kamon, who was lying to customers.

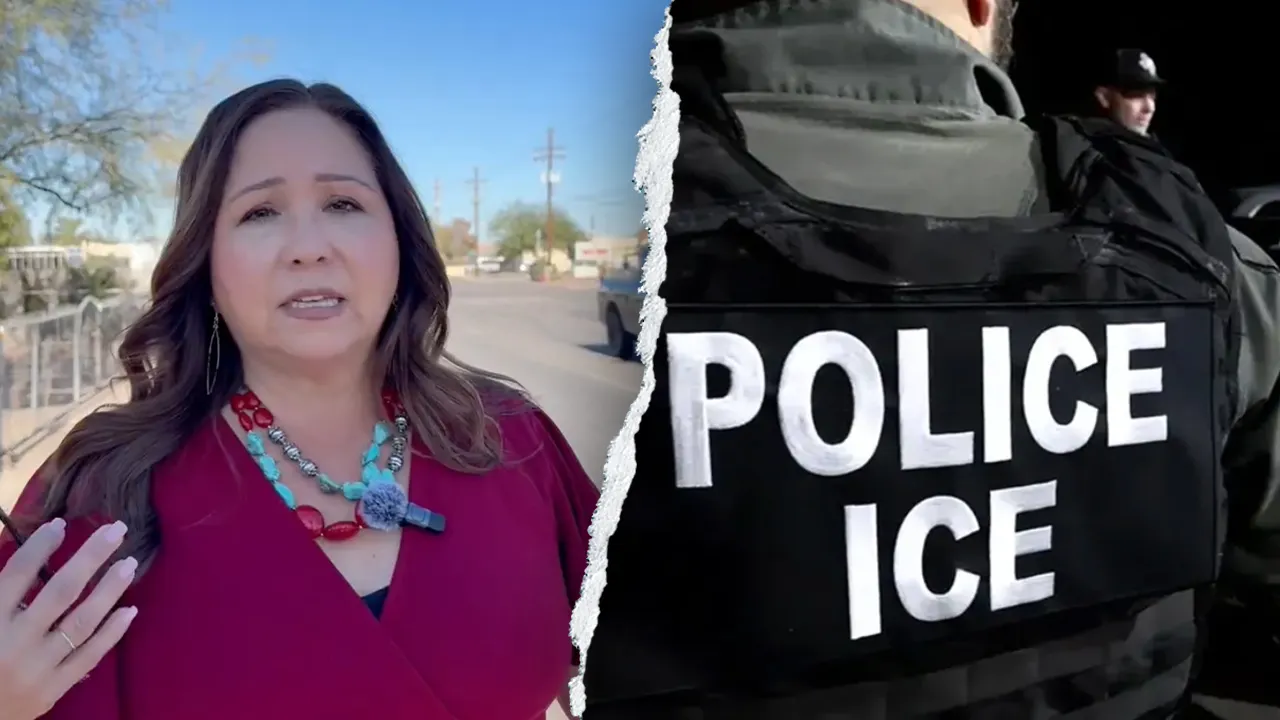

As an example, Paetty played for jurors a voicemail from around 2020 in which Girardi tells one of his clients, Josefina Hernandez, that her settlement payment was delayed because of a court order.

“I don’t want you to be mad,” he told Hernandez on the recording. “I know you are and I don’t blame you.”

Paetty told jurors there were “no more orders to sign.”

“Those were lies — her lies — and Josefina Hernandez never saw a penny of her settlement,” he said, promising jurors they would listen to other voicemails and see emails and letters that he says further show Girardi’s role in defrauding clients.

“You can see for yourself how much the defendant knew about his clients’ cases,” Paetty said.

Since Girardi’s firm collapsed in late 2020, his lawyers have claimed he is suffering from cognitive decline, and that continued Tuesday. Cross said witnesses throughout the trial would testify that Girardi’s personal hygiene had taken a backseat, that the lawyer made famous by the movie “Erin Brockovich” had stopped recognizing people he had known for years, that he reread the same emails multiple times and repeated himself in conversations.

The mental decline, Cross said, occurred during the decade at issue in the case but accelerated after a 2017 car accident. By 2020, Girardi Keese had descended into chaos, with Girardi even falling victim to “a bizarre elder abuse scheme” by an anonymous person he thought he was working on as a secret government lawyer, the defense claimed.

“Tom is not just losing his rhythm,” Cross said. “He is falling off a cliff.”