When Pete McCloskey challenged President Richard M. Nixon for the Republican nomination in 1972, his defeat was shocking. Only one of the 1,348 delegates to the Miami convention voted for McCloskey, and no one made a speech on his behalf.

Running to protest the Vietnam War, the California congressman never expected to win, but he had no idea his short-lived campaign would cost him so many friends. Outside a meeting room in the basement of the Fontainebleau Hotel, someone said he must be the loneliest man in the city, and he agreed.

“It's always a lonely feeling at conventions like this,” McCloskey, gaunt and hoarse, told reporters. “But Patrick Henry felt alone when he talked about freedom.”

McCloskey was no revolutionary, but as a decorated Navy veteran who wanted American troops out of Vietnam and as the first congressman to urge consideration of Nixon's impeachment in the House of Representatives, he led a life of vigorous dissent.

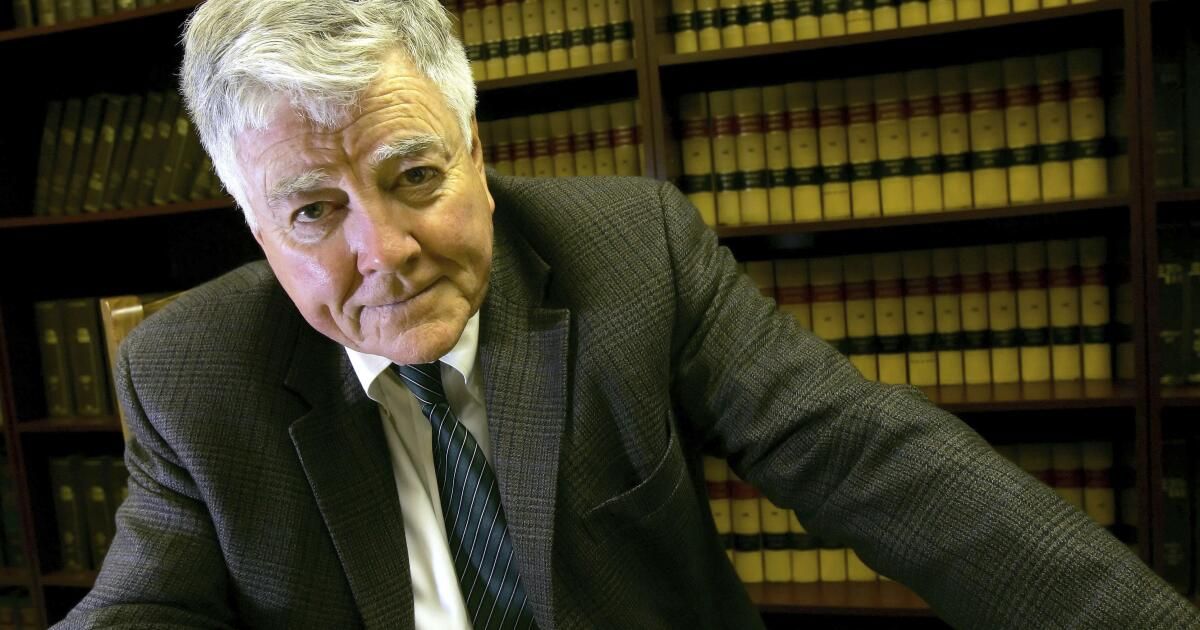

Paul Norton “Pete” McCloskey Jr., a Stanford-educated lawyer and passionate outdoorsman, died Wednesday at his home in Winters, California, said Lee Houskeeper, a longtime family friend. McCloskey was 96 years old.

The cause, Houskeeper said, was congestive heart failure.

With a photogenic square chin and a Kennedy-style mop of hair, McCloskey represented his San Mateo district in Congress from 1967 to 1983. In that period, he may have become “the only political figure in America who has managed to offend to almost everyone.” ”said his friend, actor Paul Newman, in a trailer for a 2009 documentary.

His outspokenness about Vietnam earned McCloskey exile, as he later characterized it, to the Fisheries and Merchant Marine Committee. But even in what he initially considered a congressional backwater, McCloskey managed to upset many of his fellow Republicans.

“Well, then Congress was much more inclined to be made up of people in their 70s, 80s and 90s who had grown up in an era when development and progress were the tone of the country,” he told The Times in 1985. “In those days, environmentalists were seen as little old ladies in tennis shoes, cranks, crackpots, or cranks.”

In the relative obscurity of his position, McCloskey prospered. “I was able to help form a coalition that quadrupled the money for clean water with this fun little bill called the National Environmental Policy Act,” he said. “I will tell you that if Congress had known what was in it, that bill would not have passed.”

He co-authored the Endangered Species Act of 1973, “the one thing I was most proud of, in that miserable town called Washington,” he said in a 2012 interview with environmentalist Huey Johnson.

McCloskey was co-chair of the first Earth Day. Its Democratic organizers, who crossed the political spectrum in 1970, could not find any other Republicans willing to do so.

But not all Democrats were captivated by the outspoken McCloskey, particularly after he began airing his views on the Middle East in the early 1980s. McCloskey supported Yasser Arafat, then president of the Palestine Liberation Organization. , and angered Jewish organizations with his criticism of what he saw as undue influence by the “Jewish lobby” on American policies.

In 1982, McCloskey lost to future Governor Pete Wilson in the primary election for the United States Senate. He told The Times that his controversial positions on Israel may have contributed to his defeat.

Returning to California, McCloskey practiced law in the San Francisco area before reducing his hours and moving to a ranch near the small Yolo County town of Rumsey.

McCloskey, who raised Arabian horses and grew organic olives and oranges, ran a quixotic primary campaign in 2006 against Rep. Richard Pombo, a veteran Republican congressman known for his opposition to environmental regulations. McCloskey lost, but Democrats credited him with weakening Pombo, who was defeated in the general election.

A year later, McCloskey, repulsed by a series of influence-peddling scandals and the “misdeeds and incompetence” of the George W. Bush administration, switched parties. For 59 years he had been a Republican, but in an email to local newspapers, the budding Democrat denounced “the stench of Jack Abramoff” and declared of Republican leaders: “A disease to them and their values.”

McCloskey was born in San Bernardino on September 29, 1927, and grew up in South Pasadena. His father and both grandparents were lawyers.

After graduating from high school in 1945, he served in the Navy until 1947. He earned a bachelor's degree from Stanford in 1950 and enlisted in the Marine Corps to fight in Korea. His accolades included the Navy Cross, the Silver Star and, for wounds received while leading a rifle platoon, two Purple Hearts.

At a Christmas party in 2011, he gave one of them to then-Rep. Jackie Speier, Democratic legislator from Hillsborough. As an aide to Rep. Leo Ryan in 1978, she was shot five times while helping evacuate deserters fleeing Jonestown, the Guyana commune where some 900 people died in a massacre.

“He earned it,” McCloskey told The Times. “She was hurt more than I was.”

McCloskey's injuries were also emotional. He suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder and dreamed repeatedly of peering into a trench and emptying his gun into young, terrified enemy troops.

In 2014, he traveled to North Korea and arranged a meeting with a war veteran from the other side: a retired three-star general who, like McCloskey, had been wounded.

“I told him how bravely I thought his people had fought and we hugged,” McCloskey told The Times. “We ended up agreeing that we don't want our grandchildren or great-grandchildren to fight, that war is hell and there is no glory in it.”

McCloskey is survived by his wife, Helen, his longtime press secretary, whom he married in 1978, and four children by his first wife: Nancy, Peter, John and Kathleen.

Chawkins is a former Times staff writer.