California's spring Chinook salmon were already in the midst of a population decline before the park fire erupted in the state. The fourth largest forest fire in historyBiologists now fear the fire could push the fish closer to extinction by burning forests along streams that provide critical spawning habitat.

The wildfire has been raging through the upper Mill and Deer Creek watersheds, threatening forested canyons that provide some of the last intact spawning habitat for spring Chinook salmon.

“This fire coming into the upper basin, where we have sensitive breeding and rearing habitat, is concerning,” said Matt Johnson, senior environmental scientist with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. “We have a wildfire that is occurring at a very inopportune time for the species and is being driven by a hundred years of fire suppression activities and a warming climate.”

The two streams are considered vital strongholds for federally threatened spring Chinook salmon, which have suffered long-term declines due to water diversions, dams that have prevented them from reaching spawning grounds and increasingly severe droughts worsened by climate change.

Even before the fire, biologists were so alarmed by a recent decline in the spring salmon population that last year… began to catch juvenile fish from Deer Creek to breed them in captivity.

The fire is burning near areas of streams where adult fish typically spend weeks swimming in deep pools before spawning in the fall. Young fish that hatched last winter also remain in streams this time of year and could be in danger, Johnson said.

Population surveys along the two Sacramento River tributaries have been postponed due to the fire.

A man has been accused of arson, accused of starting the fire by pushing a burning car off a cliff in Chico. The suspect denies the accusations.

Fire suppression in California over the past century has left forests with a heavy fuel load.

Biologists are concerned that if the fire burns intensely in the watershed, bare soil and ash could fill streams when rains come, severely damaging water quality and potentially killing fish.

“If we have a very intense fire that cooks the vegetation that holds the soil together, we could have increased sediment flow, debris and ash,” Johnson said.

He said that while less intense flames can be beneficial to the ecosystem, a destructive fire that kills large trees would loosen the soil, allowing it to seep into streams and harm fish.

Severely burned watersheds may also be vulnerable to landslides rushing into streams.

“We are still waiting for the fire to develop,” Johnson said. “We are very anxious about the outcome.”

The streams are sustained by spring-fed streams and snowmelt from Mount Lassen and the surrounding mountains.

The two streams flow through rocky canyons shaded by pines and Douglas firs, where ferns grow along the banks.

Salmon spawn in late September and October in clear, cold waters, laying their eggs in gravel.

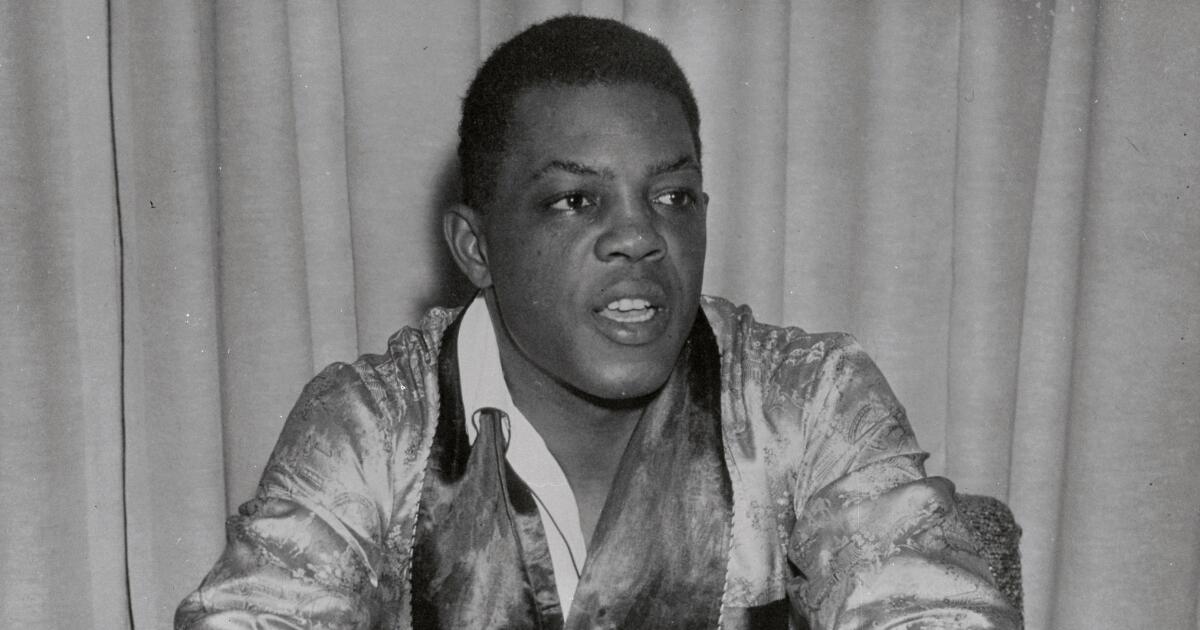

Matt Johnson, a senior environmental scientist with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, looks inside an aerated fish transport tank containing spring-fed Chinook salmon harvested from Deer Creek in 2023.

(Peter Tira / California Department of Fish and Wildlife)

Johnson has returned to the area regularly for more than 20 years to conduct studies, walking miles along trails to reach spawning grounds.

“This is one of the most beautiful salmon habitats left in the Central Valley,” Johnson said. “It’s going to hurt to see it if it’s severely damaged.”

Johnson said he expects the fire to produce a combination of effects: burning some areas intensely but leaving others less damaged. If the watershed is severely charred, he said, habitat could be degraded for years or decades.

For state scientists who have been working to help salmon, the park fire could alter their long-term strategy.

“We’ve always considered this habitat to be a safe bet,” Johnson said. “But now that quality habitat is under threat.”

The spring chinook was listed as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act in 1999.

“How bad it is for fish really depends on the details of how it’s burned,” said Steve Lindley, director of fisheries ecology at NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center. “If it’s completely denuding the hillsides and killing all the vegetation, that’s bad. If it burns down to the water, that’s bad, too. That doesn’t usually happen. The riparian zone around streams often resists burning because it’s quite a bit wetter than upland vegetation.”

After suffering declines during successive droughts, reduced spring salmon populations now rely heavily on these two streams, as well as Butte Creek, another Sacramento River tributary.

If some of the habitat is lost, Lindley said, “there's really not much that can be saved elsewhere because there are very few other populations and they're all relatively small.”

“These populations suffer greatly during droughts,” Lindley said. “It’s one thing after another. It’s been building up to the point where they’re really on the brink of extinction.”

Scientists have warned for years that large, destructive wildfires could harm remaining salmon populations. Lindley and other scientists said in a 2007 Report that wildfires in the headwaters of Mill and Deer creeks, as well as Butte Creek, pose a significant threat to spring Chinook salmon.

The fish were once abundant in rivers and streams throughout the Central Valley, but dams have kept them from reaching many of their mountain stream habitats.

And while salmon are adapted to survive California's natural fire cycles, their low numbers combined with larger, more destructive fires now create a potentially lethal mix.

“What we have now are these mega wildfires that are intensified by climate change. And we have reduced fish populations because of all these other impacts — dams, water withdrawals, pollution,” said Andrew Rypel, a professor of fish ecology and director of the Center for Watershed Sciences at UC Davis. “They’ve already been weakened by all these other impacts.”

Rypel said he is concerned that this fire, and others like it, could “wipe them out or make things much worse.”