SAN FRANCISCO— Philanthropist and Levi's heir Daniel Lurie won the close race for mayor of San Francisco, ushering in a new era of leadership for a city whose voters have made clear they are fed up with brazen retail theft and tent cities. expanding campaign.

It took two days to determine a winner under San Francisco's ranked-choice voting system, which allows voters to select multiple candidates in order of preference. The city uses a multi-round process to count ballots, and it may take several rounds of counting before a winner receives more than 50% of the vote. Although thousands of votes remained uncounted Thursday night, the gap in support between Lurie and his opponents was deemed too large to bridge.

Lurie, a centrist Democrat, bested incumbent Mayor London Breed and three other prominent local Democrats, receiving 56.2% of the total ranked-choice votes, compared to Breed's 43.8% as of Thursday's count.

Board of Supervisors Chairman Aaron Peskin, the only leading candidate running as an old-school progressive, came in third after being eliminated from the race with 21.6% of first-choice votes, and venture capitalist Mark Farrell, a moderate, trailed in fourth place. . Supervisor Ahsha Safaí was eliminated early from the race after earning just 2.7% of first-choice votes.

Lurie did not immediately issue a statement after the race was called Thursday. But at an event on election night, he outlined his vision for leadership to jubilant supporters gathered at a music venue in the Mission district to cheer him on.

“Our challenge and opportunity is to show how the government can deliver on its promise of a safer, more affordable city,” Lurie said. “And keeping these promises requires us to be brave, compassionate and honest.

“It has never been clearer to me that so many people love this city, and it's time we start making people feel like the city loves them too.”

In a statement posted to social media Thursday night, Breed said he had called Lurie to congratulate him.

“Being mayor of San Francisco has been the greatest honor of my life. “I am beyond grateful to our residents for the opportunity to serve the City that raised me,” Breed wrote. “During my final two months as mayor, I will continue to lead this city as I have since day one: as San Francisco's greatest advocate.”

The transition from Breed to Lurie marks a notable turn on many fronts.

Breed, 50, made history six years ago when she became the city's first Black mayor. She was born into poverty in the Western Addition, at the time one of San Francisco's toughest neighborhoods, and was raised by her grandmother. He lost a sister to a drug overdose and has a brother in prison for robbery. Before being elected mayor, she was president of the powerful Board of Supervisors.

Lurie, 47, was also born in San Francisco, the son of a rabbi. His parents divorced when he was a child and his mother, Miriam Haas, married Peter Haas, who helped raise Lurie. The late Peter Haas was the great-grandnephew of Levi's founder and a longtime company executive. Lurie and his mother are among the primary heirs to the Levi Strauss family fortune. Lurie had never before held elected office.

Throughout the campaign, Lurie distinguished himself as a political outsider running against four City Hall veterans. He promised to root out government corruption, a concern among voters after a series of political scandals in city departments and non-profit organizations in recent years.

The election was widely viewed as a referendum about Breed's efforts to address homeless encampments, crime and a weakened post-pandemic economy that affects voters' sense of a safe, well-functioning city.

“This is not an election that has to do with an ideological or political shift or a rejection of Breed,” said Jason McDaniel, a political science professor at San Francisco State University. “He is an outsider who is different and who knew how to present himself in that way as someone who will do things differently.”

In a marked change for San Francisco, the city's rich tech sector played an influential role in this year's race. The tech titans who have put down roots in the city poured millions of dollars into campaign contributions, pushing for an outcome that would infuse this famously liberal city with more centrist politics.

That money overwhelmingly benefited Lurie, Farrell and Breed.

“It's been a multi-billion dollar election,” said Jim Ross, a veteran Bay Area Democratic strategist.

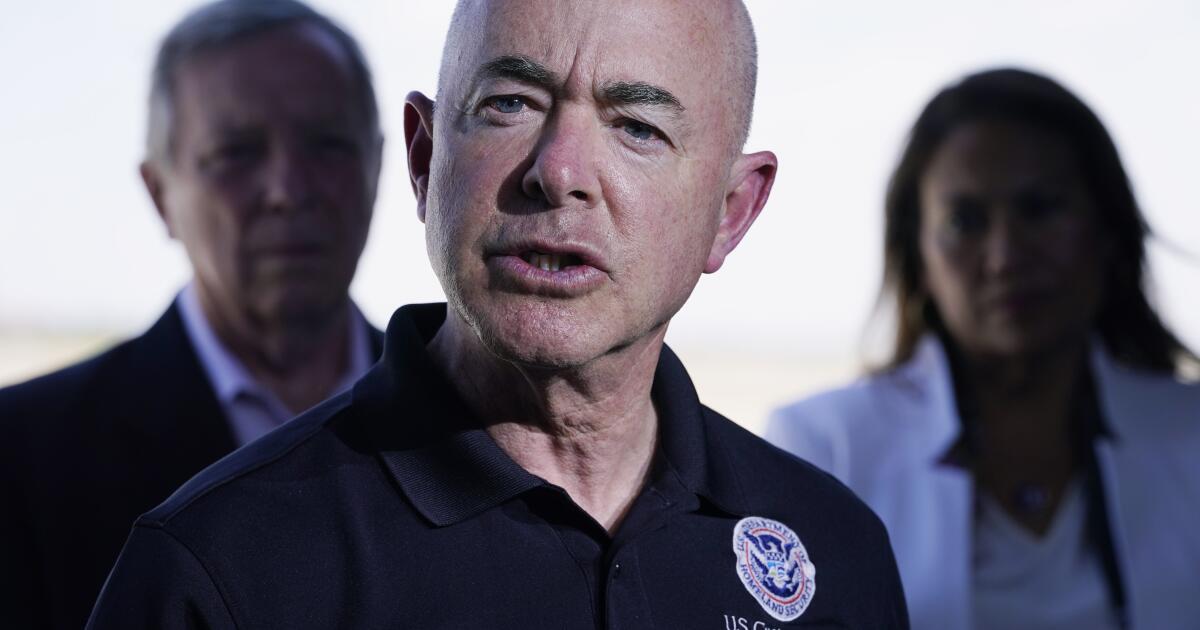

San Francisco Mayor London Breed faced a tough re-election bid against four rivals who said she had not done enough to address property crime and homelessness in the city.

(Eric Risberg/Associated Press)

Breed was first elected in 2018, winning a special election after the unexpected death of then-Mayor Ed Lee. He led the city through a challenging period that included the troubling early spread of COVID-19 and the subsequent exodus of dozens of downtown tech workers who, amid pandemic-related closures, were able to work remotely, and more economical way, from other cities. .

Breed has never been a bloody-hearted progressive, despite San Francisco's liberal reputation. But the Race of six years ago was more open to experimenting with a progressive reformist agenda when it came to solving difficult issues like addiction and poverty.

In the past two years, by contrast, he has become a leading voice in a movement to crack down on homeless people and addicts who refuse shelter or treatment. And this year he successfully championed two local ballot measures that strengthened policing powers and will require drug testing and treatment for people receiving county welfare benefits who are suspected of using illicit drugs.

Many of his supporters touted his swift action to shut down San Francisco in the early days of the COVID emergency, a decision credited with saving thousands of lives. And he gained influential endorsements from housing organizations thanks to his work to alleviate the affordable housing shortage in San Francisco.

In defending his re-election, Breed highlighted recent data showing improvements in some of San Francisco's biggest problems, particularly a reduction in property crime and violent crime over the past year.

Their opponents dismissed that progress as too little, too late, and took advantage of voter dissatisfaction to present themselves as more qualified alternatives.

Both Lurie and Farrell promised a more concerted fight against crime and homelessness and revitalizing the downtown economy.

Lurie had the advantage of his family's great wealth to strengthen his name recognition. He showered his campaign with more than $8 million of his own money. His mother contributed more than a million dollars to an independent committee supporting his mayoral bid.

He touted his role as founder of Tipping Point, a San Francisco nonprofit that funds efforts to lift people out of poverty, to highlight his commitment to solving difficult problems. He said the organization has funneled $500 million to Bay Area organizations focused on early childhood education, scholarships, housing and job training since its founding nearly two decades ago.

Farrell entered the race with support generated during his seven years as supervisor, arguing that his combination of political and business experience made him more qualified to get San Francisco back on track. But his campaign failed amid ethical concerns. This week he agreed to pay a $108,000 fine following an ethics investigation that determined he had illegally funded his mayoral campaign with money invested in a separate ballot measure committee he sponsored to reduce the number of government commissions in San Francisco.

Peskin, a long-time supervisor, organized a solid base campaign centered on traditional liberal ideals, such as making the city affordable for nurses, teachers, and artists and bohemians who have long made San Francisco a creative hub.