When a renewable energy company began to devastate thousands of Joshua trees this month to make way for an extensive solar farm, unleashed a storm of indignation among Mojave Desert residents and activists.

It was a public display of the thorny dilemma conservationists face as they fight to preserve the Joshua trees of the west. While the state is close to completing a draft conservation plan later this year, both climate change and solar projects are threatening the desert habitat of these iconic trees.

Climate scientists predict that by the end of the century, Western Joshua trees will be able to survive on just 10% to 25% of the land they now inhabit. And, as the Mojave and Colorado deserts continue to become hotter and drier, succulents will likely disappear almost entirely from Southern California. even from Joshua Tree National Park.

The problem, experts say, is that while many species can move north and to higher elevations to escape rising temperatures, Joshua trees migrate very slowly and can't keep up.

“Joshua trees are in this triple bind,” said Christopher Smith, a biology professor at Willamette University who co-wrote a paper 2023 exploring how to balance solar development and Joshua tree conservation.

First, there is climate change, Smith said. Then there is habitat loss due to urbanization and solar development. Finally, there are increasingly intense forest fires, which can clean considerable percentages of all living Joshua trees in a single season.

“There are some places,” Smith said, “where half the trees have died, according to our censuses, in the last 15 years.”

After effort of years failed to get western Joshua trees, a distinct species from their eastern counterparts, listed as endangered in 2022, climate advocates and the state developed a law to preserve them. He ordered the California Department of Fish and Wildlife to draft a conservation plan backed by science and Native Americans by the end of 2024, and imposed fees for the removal of Joshua trees, fees that would be used to fund the work of conservation.

During years, environmental groups and even governmental agencies They have talked about moving the plants as far north as Oregon to climates that will resemble Southern California in a hundred years. However, Joshua tree scientists say transplanting the species is not so simple.

Among other barriers to relocation, Western Joshua trees depend on a unique species of yucca moth to pollinate them. They also require a single, underground fungal network that carry nutrients to the trees. And scientists say there may be other species that the plants depend on that they haven't yet identified.

“I think most people would say it's a Hail Mary step,” Smith said of relocating the plants a long distance. “To have those [trees] As a long-term legacy, and not just the zoo animals, you also need to have a functioning ecosystem.”

A Joshua tree in Juniper Hills is consumed by the Bobcat Fire in 2020. Wildfires, along with climate change and habitat loss, are taking an increasing toll on Joshua trees in California.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

Instead, the Department of Fish and Wildlife is going on the defensive and focusing on protecting trees in select places where they have a better chance of surviving. Scientists are using models of future climate and maps of Joshua tree locations to identify areas within the trees' current habitat that will still have an acceptable climate a hundred years from now.

Many of these areas, called climate refugia, are small, meaning scientists need extremely detailed maps to identify them. So a team from the United States Geological Survey set out to create one. They studied nearly 1 million points across more than 50,000 square miles on Google Earth; They then traveled more than 9,000 miles on paved and dirt roads during 30 site visits to verify that the trees they saw in the satellite images were really there.

The resulting data set, launched in December 2023, is the battle map of the state's army of conservationists and scientists. They are using it to identify refuges across the region: places where they can deploy all the defenses in their arsenal and protect the strongholds of real estate developers, wildfires, heat waves and drought.

Measures could include removing flammable undergrowth, planting new Joshua trees, and also working to conserve the entire ecosystem the trees depend on, including moths and fungi. The state has also asked scientists to study how to make trees more resilient.

Smith and his colleagues have sequenced the genomes of 300 Joshua trees and counting. From genetic maps like these, scientists have discovered that some populations of Joshua trees have genes that make them more resistant to warmer, drier conditions.

Although no research has yet been published on the topic, there is preliminary evidence that roots adapted to better harvest nutrients with fungi may be better able to sprout a new tree after a wildfire, according to Smith. This nascent body of research could help the state introduce specific adaptations into refugia and generally keep genetic diversity high, essentially helping Joshua trees adapt more quickly to climate change.

However, the state's focus on refuges does not mean that all other Joshua trees are doomed. The conservation law includes a tree relocation program to move trees threatened by real estate development to these climate refuges. Conservation of wild landsA nonprofit with dozens of preserves across the Western U.S., it also wants to provide homes for relocated Joshua trees.

In 2006, the Sawtooth Complex Fire decimated a Joshua tree forest within the conservancy's 2,500-acre Pioneer Mountains Reserve, which is located just northwest of Joshua Tree National Park. Tim Krantz, the group's conservation director and professor emeritus of environmental studies at the University of Redlands, hopes to partner with the state to rebuild that forest with transplanted Joshua trees.

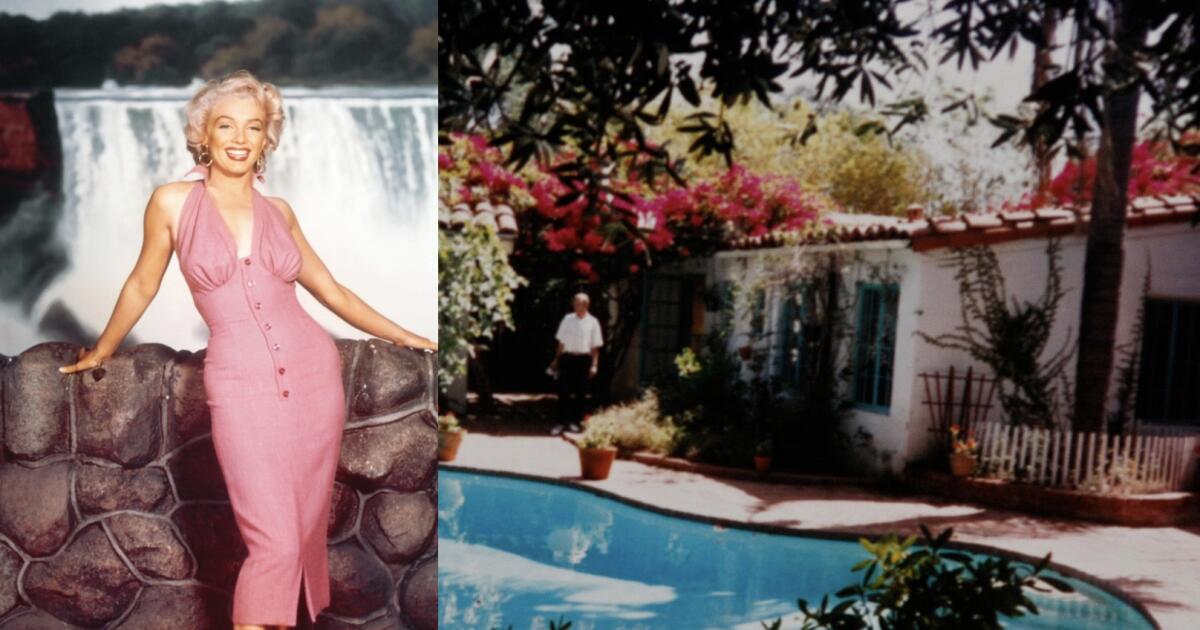

Thousands of Joshua trees, like this large specimen estimated to be between 150 and 200 years old, will be removed from the outskirts of Boron to make way for a vast solar array.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

But moving an entire forest is neither easy nor cheap. Conservationists need large hydraulic tree shovels to scoop up the plants and surrounding soil. And when replanting the tree elsewhere, caretakers must ensure that the succulents are on the same side facing north and follow an intensive watering regime for the first few years after their move.

“We expect to move hundreds of trees, and at that scale… there's a lot of monitoring and maintenance that goes on, a lot of people on the ground,” said Krantz, who co-owned a landscaping company that frequently moved trees, including Joshua trees. .

While Krantz hopes the conservation fund can support the work, the fund, which finances all aspects of conservation, likely won't have enough money to pay for the entire costly process of relocating every tree threatened by real estate development.

Scientists, state officials and tribes are still debating the details of the conservation plan, but the Department of Fish and Wildlife is not waiting to act. One of the first steps in creating ecological fortresses around Joshua Tree refuges is to ensure that the state owns the land or has permission to conduct conservation work there. In 2023, the department completed its first land acquisition with the non-profit organization Native American Land Conservation.

The site is not only a possible refuge for Joshua trees, but also a cultural site for the Kawaiisu tribe. Now, the land will be permanently conserved by the tribes and the conservation entity, which voluntarily entered into a legally binding conservation easement, facilitated by the state.

“It really reassures everyone to know that the land is set aside forever for its intended purposes, because it is recorded,” said Nicole Johnson, an attorney who works with tribes and a board member of the Native American Land Conservancy.

A desert ecologist leaves a Joshua tree study site in Joshua Tree National Park in May 2023.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

In addition to partnering with the Native American Land Conservancy, the state is working with more than a dozen Native tribes to co-manage the conservation plan and combine science with traditional ecological knowledge. However, building relationships with tribal governments takes time, said Drew Kaiser, a senior environmental scientist with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife who is coordinating development of the conservation plan. The co-management aspect of the plan is still in its early stages.

The department is also working with the solar project in the Mojave Desert near Boron to conserve more than 80,000 acres of Joshua tree habitat. according to the company. The State demanded the company pay. more than 1.3 million dollars into the conservation fund to compensate for the damage. However, the company does not plan to relocate any of the 4,700 trees.

For Smith, it is a reality of the situation in which the State finds itself. “Many species are going to go extinct and many populations of Joshua trees… are going to go extinct. “What we are doing now is stopping the bleeding and deciding who to save.”

Newsletter

Towards a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and be part of the conversation and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.