Two members of the Los Angeles Board of Water and Power Commissioners — a former Democratic congressman and a City Hall veteran — privately discussed a DWP contract with executives at a cybersecurity company, an exchange that is raising concerns among ethics experts. .

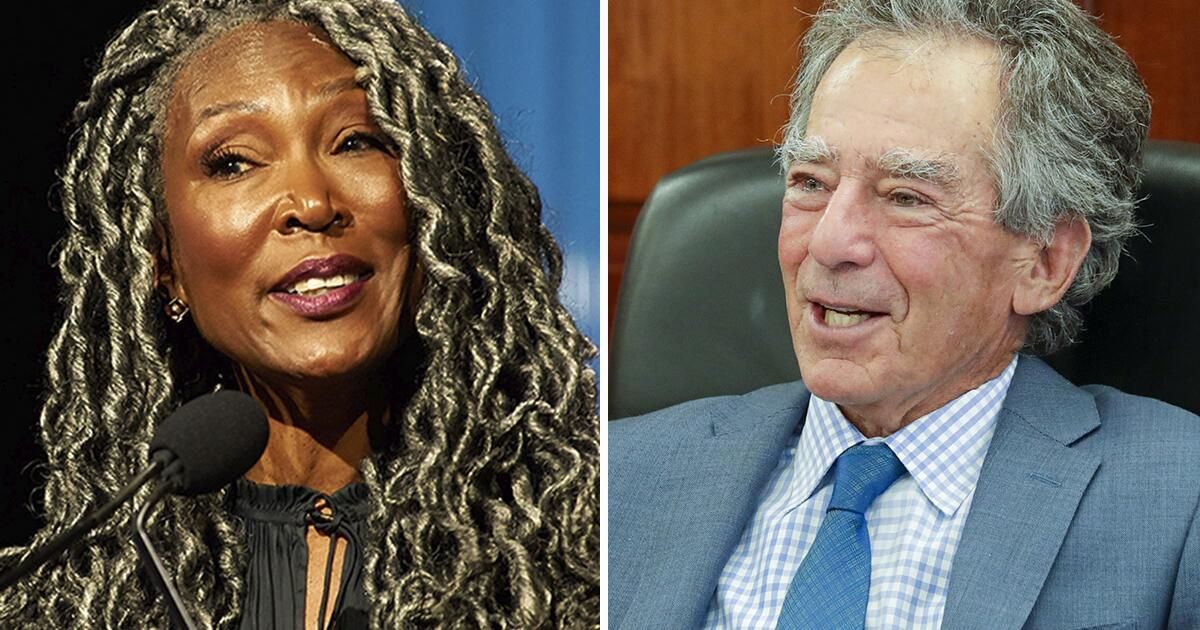

Then-DWP committee chair Mel Levine and then-vice chair Cynthia McClain-Hill held a roughly 36-minute phone call in 2019 with two executives to explain the utility’s plans to award them a contract.

Weeks later, commissioners voted to approve a 60-day, $3.6 million contract with the company and two other firms. Under the agreement, cybersecurity company Ardent Cyber Solutions was estimated to get about 75% of the work.

The city’s ethics law prohibits commissioners from privately participating in the review or negotiation of contracts on which they will vote. DWP board rules also prohibit commissioners from having private discussions about bids with suppliers.

Both Levine’s attorney, Daniel Shallman, and McClain-Hill said the conversation was appropriate. The aim was to ensure that Ardent executives, who worked in DWP cybersecurity under a different contract, remained in work at the utility, they said.

Both also said the aim was to protect the DWP, which could face attacks on its water supply and power grid.

On the call, which was secretly recorded, commissioners discussed billing, when the DWP board would vote on the contract and the date the utility would give the company its first work order.

DWP commissioners are volunteers appointed by the mayor. They vote on multimillion-dollar contracts at public meetings, oversee the department, and carry out the mayor’s policies.

FBI agents outside the DWP headquarters in 2019.

(Al Seib/Los Angeles Times)

Levine and McClain-Hill’s attorney said the two commissioners were not involved in the investigation of Ardent as a supplier, or any other aspect of the competitive bidding process for cybersecurity work, because that was handled by the State Public Power Authority. Southern California.

The electricity authority is a group of about a dozen utilities, including the DWP, which enters into framework agreements with suppliers for its members.

In Ardent’s case, the DWP opted for its own short-term contract with the company, rather than seeking work through the electricity authority’s agreement.

Under its own contract, the DWP could set its own terms for Ardent’s billing schedule, but also rely on the power authority’s vetting process, McClain-Hill told executives on the call.

McClain-Hill, now chairwoman of the DWP commission board, acknowledged to the Times that it was unusual for her and Levine to become involved in the discussion that would normally be handled by staff.

“During my tenure as a member of the Board of Water and Power Commissioners I have always behaved ethically and have never engaged in any unlawful or unlawful conduct,” McClain-Hill said.

Shallman, Levine’s attorney, said the transcript of the call shows that “Mel acted in the best interests of DWP and its clients, and fully complied with all applicable laws.”

Levine represented the Los Angeles area for a decade in Congress until 1993 and left the DWP board in 2020.

Some ethics experts interviewed by The Times questioned whether commissioners complied with the city’s ethics rules.

Section 49.5.11 of the city’s ethics ordinance states: “Except at a public meeting, a member of a City board or commission shall not participate in the development, review, evaluation or negotiation or recommendation process of bids.” , proposals or any other request for the award or termination of a contract, amendment or change order involving that board, commission or agency.”

Other sections of the ordinance prohibit commissioners from disclosing confidential information.

Even if the Southern California Public Power Authority chose Ardent for a contract, the DWP had final contracting authority, so “communication remains inadequate,” said Neama Rahmani, a former assistant U.S. attorney and former director of law enforcement from the city’s Ethics Commission. .

“Bad bad bad. Period,” said Laura Chick, former Los Angeles City Controller and City Council member. “They should not have a separate conversation with a bidder. And you should probably never have a private conversation with them unless staff are present.”

Levine and McClain-Hill, both attorneys, were appointed to the DWP board by then-Mayor Eric Garcetti. The phone call first came to light in legal documents, but the full discussion had not been previously reported.

The Times reviewed a recording of the phone call and emailed a transcript to Levine and McClain-Hill.

The call appears to have been secretly recorded by Paul Paradis, a former lawyer turned FBI informant in the government’s City Hall corruption investigation.

Paradis said in Federal Bankruptcy Court documents that he recorded Levine and McClain-Hill on April 5, 2019, as part of his work for the FBI. Paradis’ court filing was reported in 2022 by Knock LA and Debaser.

Paradis declined to comment on the audio reviewed by The Times. US Attorney’s Office spokesman Thom Mrozek also declined to comment.

Paul Paradis, who arrives at federal court in downtown Los Angeles in June, said he secretly recorded the conversation involving the two DWP board members, according to court documents.

(Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times)

The phone call came as the corruption scandal unfolded at the highest levels of the DWP and the city prosecutor’s office. It would come to light when the FBI raided the two city apartments in July 2019.

The government investigation focused on cybersecurity contracts, illicit payments and a bogus lawsuit over faulty DWP invoices. Paradis worked on the city’s lawsuit and secured contracts with DWP before helping the FBI.

DWP chief executive David Wright later pleaded guilty to a bribery scheme involving Paradis’ cybersecurity firm.

Another top DWP executive, David Alexander, later admitted to rigging Ardent’s contract approval through the Southern California Public Power Authority by manipulating scoring through his role on the authority’s cybersecurity committee. energy.

Prosecutors have never suggested that McClain-Hill, Levine or the two Ardent executives, Jeremy Dodson and Ryan Clarke, knew of Alexander’s manipulation.

At the time of the phone call, Dodson and Clarke had been working at DWP through Paradis’ company, known as Aventador. Dodson and Clarke formed their own company, Ardent, after the DWP board canceled the Aventador contract when media reports questioned Paradis’ role in the bogus lawsuit.

In the call, McClain-Hill told Dodson and Clarke that the power authority was approving Ardent as a supplier. Then, he explained, the DWP would contract directly with Ardent so the utility could “determine the frequency of payment, the terms and conditions of how it happens.”

Levine is heard assuring cybersecurity executives that the two commissioners would support the contract when it comes before the DWP board.

“We need three votes, and here we have two,” Levine said at one point, outlining a timeline for approval.

Dodson and Clarke did not respond to requests for comment. Neither has been accused of wrongdoing.

Commissioners also discussed a strategy to shift public attention away from Ardent, and McClain-Hill told executives the plan is to “dim the attention a little bit” on the company. Under the strategy, a second security company, Archer, and possibly a third would be added to the DWP contract, McClain-Hill said on the call.

McClain-Hill, who previously served on the city’s police commission, told The Times that she did not reveal any confidential information on the call and that her “notable” comment was about protecting the reputations of Dodson and Clarke amid scrutiny from the media about Paradis.

He became involved with Ardent because of his concerns at the time about the trial of Wright, then a senior DWP executive, he told The Times.

Additionally, McClain-Hill said he knew the Southern California Public Power Authority was going to choose Ardent as a supplier because Wright told him before the April 5 call.

The power authority’s cybersecurity committee formally recommended Ardent as a bidder on April 5. Weeks later, on April 18, the Southern California Public Power Authority board approved a framework agreement with Ardent and the other companies.

McClain-Hill continued to communicate with Clarke, telling her in a text message days before the DWP board vote that Garcetti’s office wanted the contract to be split into three separate deals so that none were a double-digit amount. The text of April 19, 2019 was reviewed by The Times.

“We will approve a second contract in 45 days and a third contract 45 days later,” McClain-Hill wrote to Clark. “We’re finally at the end of this road…I hope this works out for you.”

On April 23, 2019, McClain-Hill, Levine and other DWP board members approved the utility’s contract with Ardent, Archer and another company.

Shallman, Levine’s attorney, when asked about Claims that the DWP had final contract authority so commissioners should not have been discussing the contract, Levine said “was in full compliance with all applicable laws.”

“Rather than showing any effort to improperly influence the hiring process or engage in prohibited negotiations, the transcript shows a good faith effort to ensure continuity of service by qualified professionals in whom DWP had already invested time and money “Shallman said.

“Put simply, Mel didn’t want to leave DWP vulnerable to cyber threats because the experts they had hired were scared by DWP bureaucracy or worried about not getting paid,” he said.

Sean McMorris, director of California Common Cause’s transparency, ethics and accountability program, questioned why staff, rather than commissioners, weren’t speaking to Ardent.

“If the meeting was to discuss the contract and tell the company that they are going to vote for them and what the contract would be like, that type of thing should not happen in a private forum,” he said.

“Even if it’s legal, it doesn’t seem appropriate,” McMorris added.