As diplomats from around the world gather in Jamaica next month to discuss international guidelines on deep-sea mining, environmental activists are urging nations to consider a California law that they say could mitigate the need to destroy the fragile ocean ecosystems.

“Deep sea mining will destroy one of the most mysterious and remote natural areas on the planet, all to extract the same metals we throw away every day,” said Laura Deehan, state director of the Center for Environmental Policy and Research. Of California. “As we work to protect California's coastal ocean life, we must join calls to protect the deep ocean before it is too late.”

The report was prepared by experts from the environmental groups Environment America and US PIRG, as well as the Frontier Group, a nonprofit environmental research firm and think tank.

As the world transitions away from fossil fuels, many replacement technologies (electric vehicles and wind turbines, for example) rely on metals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper and rare earths. And as production increases, international mining conglomerates are increasingly looking to the depths of the ocean, where large quantities of polymetallic nodules (natural concentrations of many of these metals) have been located.

Deep-sea polymetallic nodules can fit in the palm of your hand and contain many elements critical to modern technologies.

(Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times)

These nodules, formed over millions of years, measure between one and four inches in diameter and are found within the top three inches of the ocean floor.

Now, mining companies like Canada's Metals Co. want to take their deep-sea collectors or underwater collectors to the ocean floor and rake them across the sea floor to grab these “rocks” as they traverse the cold, dark waters of the deep ocean. .

Their first target: the Clarion Clipperton zone of the Pacific Ocean, which extends west of the Central American coast about 4,500 miles and encompasses approximately 1,700,000 square miles.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

In 2016, an international team of scientists investigated the seafloor there and found that it contained a wealth of diverse marine life. More than half of the species collected were not only new to science, but they also found a positive association between the amount of marine life and the number of nodules.

The Metal Co. and its supporters of deep-sea mining say their industry is essential to providing the raw materials needed to combat fossil fuel-driven climate change.

“Metal extraction, whether on land or in the deep sea, will affect ecosystems…”, the company acknowledges on its website. However, “the transition to clean energy will require trade-offs.”

But the authors of the new report (and other experts) say that's not true. They argue that technological innovation, targeted recycling of electronic waste, and laws that allow consumers to extend the life of their electronic products can meet this need.

“I agree with the deep sea mining industry that climate change is our greatest planetary challenge, our gravest threat…if there was anything that deserved the title of existential crisis, it would be that,” said Douglas McCauley, associate professor from the Department of Ecology, Evolution and Marine Biology at UC Santa Barbara, who was not involved in the report.

But, he said, “it's a hoax, a lie that if we want to address climate change or take meaningful climate action, we have to exploit the oceans.”

In 2021, the Pacific island nation Nauru, in partnership with Mineral Co., notified the International Seabed Authority, an intergovernmental body of 167 member states and the European Union established under the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) of 1982. – of plans to start mining in international waters. The move triggered the “two-year rule” of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which required the board's 36-member council to consider and provisionally approve mining applications by July 9, 2023.

The council missed that deadline and ended its meeting without finalizing the regulations. The council is now working to adopt regulations by 2025.

Next month, the council will begin deliberations in Jamaica and environmentalists hope to persuade it to ban deep-sea mining, or at least issue a moratorium.

They say innovations in battery technology and production, as well as recycling and right-to-repair laws, will make the need to continue this destructive practice obsolete.

“Why go destroy one place and jump to the next to destroy it and get new minerals, when suddenly we have new technologies that help us increase circularity and close the loop, taking materials from the reserves we already have?” he said. McCauley. .

According to the report, consumers throw more copper and cobalt into discarded electronic waste each year than Metals Co. could produce through 2035 in the Clarion Clipperton area.

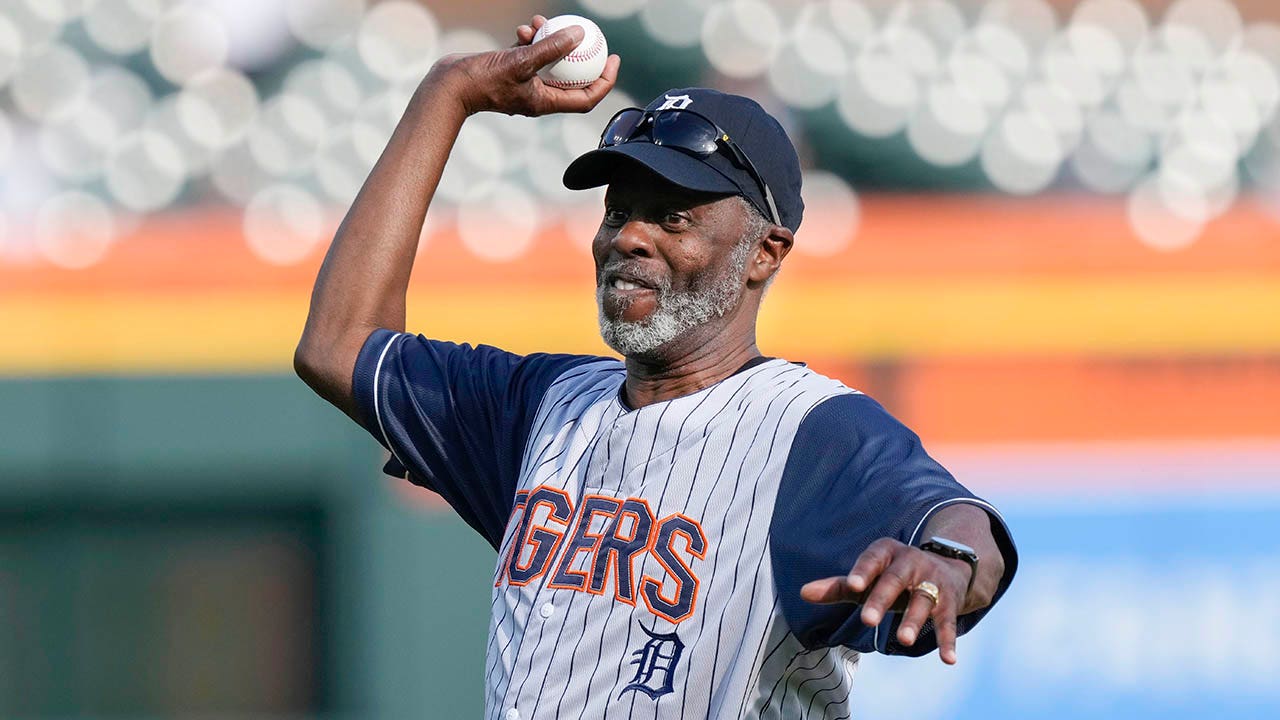

Gerard Barron, president and CEO of Metals Co., in front of a mining research vessel in San Diego in June 2021.

(Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times)

And they say extending the life of electronics by repairing and reusing them could reduce the need for new materials. For example, doubling the shelf life of a product can reduce demand by 50%, while increasing the shelf life of products by only half can reduce demand by a third.

“Right now we are throwing away 47 pounds per person of e-waste every year,” said Fiona Hines, legislative analyst for CALPIRG. “That's 3 million tons a year in the United States”

Currently, California, Massachusetts, Maine, Colorado, Minnesota and New York are the only states with right to repair laws, however 30 more are considering bills.

Deep-sea mining operations are not currently taking place anywhere in the world's oceans, although pilot and test trials have been conducted to evaluate the ecosystem response to the extraction of nodules from the ocean floor.

Those experiments and models have shown irreparable local damage, as well as more widespread damage caused by the sediment clouds that such activities could spread in ocean currents.

“These are some of the least resilient ecosystems on the planet,” McCauley said.

Mining them would create “damage that so far in all our studies we have not seen recovered,” he said, referring to a 1989 mining simulation off the coast of South America, which has still not been recovered 35 years later.

He said the deep-water zone is not like shallower regions of the ocean, such as Bikini Atoll in the central Pacific, on which 23 atomic bombs were dropped between 1946 and 1958, but is possibly flourishing today, having recovered corals, fish, turtle populations and invertebrates. Or like a rainforest, which can be devastated, but over time it will grow again, although not with the old.

In regions proposed for deep-sea mining, nothing seems to be working again, he said.

“There are physical reasons for this: we are talking about a space that has very little light, very little energy, extremely cold temperatures and high pressures. So life down there moves at a much, much slower pace,” he said.

And then there are the plumes of sediment that could block sunlight or cloud normally clear waters, which worry fishermen and environmentalists. Unlike land operations, these plumes, tailings and waste cannot be confined, and models show them moving hundreds or thousands of kilometers.

“There are no recognized boundaries for wildlife in the ocean,” said Deehan, California's state director of the Environment. He observed the Pacific leatherback turtle, which is considered endangered. “Every year it travels from Indonesia, across the Pacific Ocean, to California. And then there are the whales that migrate around the world. “These ecosystems are all interconnected and support wildlife in our ocean.”

Newsletter

Towards a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and be part of the conversation and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.