“Welcome to Book Rack,” says Karen Kropp, as her eyes scan the dwindling shelves inside her bookstore.

“Before it was much more crowded.”

After 40 years, the last half under Kropp ownership, the beloved used bookstore nestled between a stew restaurant and a chiropractor's office in Arcadia will close this week.

Slowed by consumers' shift to online shopping and further decimated by falling sales during the pandemic, the store has been hanging on by a thread in the months since Kropp cashed in on its life insurance policy to keep it alive. float.

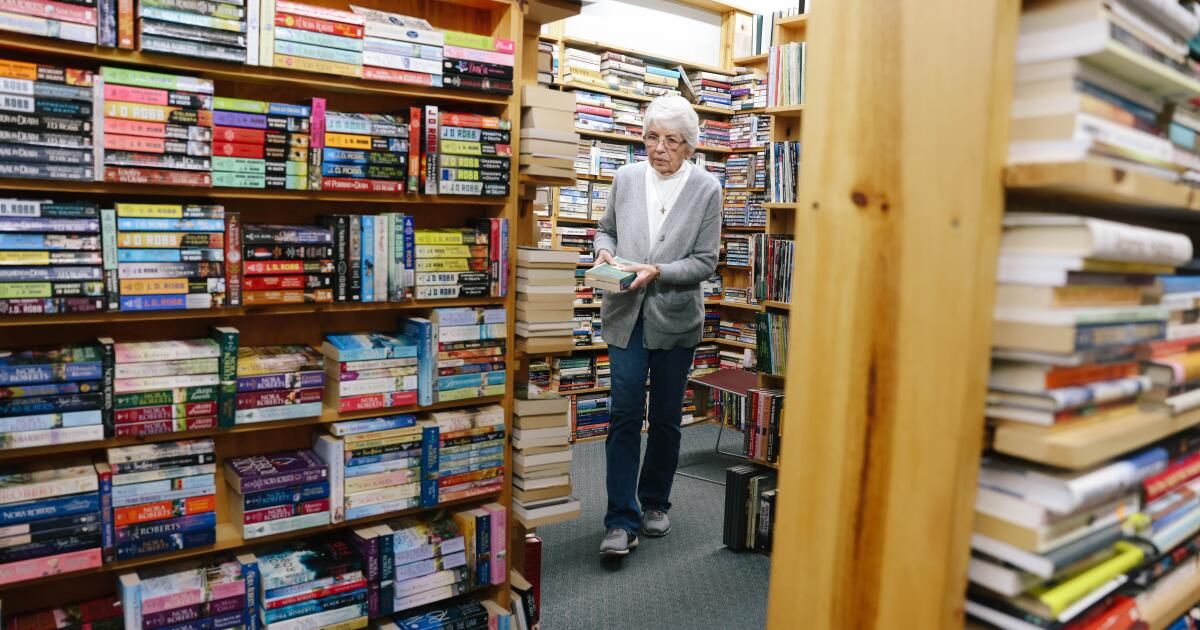

Karen Kropp pauses among the increasingly empty shelves at Book Rack, a bookstore she has owned for nearly two decades.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

“The miracle is coming,” Kropp often assured himself. “When you're in a bookstore, you have to be a dreamer.”

But the miracle never came, and Kropp, who will turn 79 later this year, knew that even if he couldn't afford it, it was time to retire.

She plans to live off her monthly Social Security check (about $1,200 after deducting insurance premiums) and can't afford to stay in Southern California. Instead, she will move in with her younger sister in Albuquerque once she finishes cleaning the store.

“When you're in a bookstore, you have to be a dreamer.”

—Karen Kropp, owner of Book Rack

“I put everything I had into this place,” he said. “All.”

Kropp's situation reflects that of many aging small business owners who, unless they have a relative eager to take over, face complex questions about their legacy and finances.

In January, the owner of Vroman's, a historic independent bookstore in Pasadena, announced on Instagram that, as his 80th birthday approached, he planned to retire and sell the store to someone outside his family.

“This was not an easy decision for me,” he wrote, adding that the store had been under the management of his family for more than a century.

The owner of Vroman's Bookstore in Pasadena recently announced that he plans to retire and sell the bookstore to someone outside of his family.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Retirement in the U.S. is a fragmented system with “a big gap” for self-employed workers like Kropp, who never worked for a large employer that offered 401(k) matching contributions, said Nari Rhee, director of Retirement Security. The retirement. Program at the UC Berkeley Labor Center.

Someone in Kropp's situation (a single renter living in Los Angeles County) needs $2,915 a month to cover basic needs, Rhee said, citing a figure calculated using the elderly index, a tool developed by the University of Massachusetts Boston to measure how much older Americans need to cover basic living expenses.

“That's basically double the average Social Security benefit in California,” Rhee said, noting that in recent years, more older Californians have fallen into poverty and aged homeless.

“It's a crisis.”

Nearly 30 years ago, shortly after moving west from Green Bay, Wisconsin, Kropp got a job at Book Rack, then on Baldwin Avenue, a short distance from his current location.

She started out as a clerk, earning about $3 an hour pricing and organizing books, and she adored her boss, Pat Carlson, the store's original owner. For someone whose main childhood complaint with the library was that it limited the number of books she could check out at a time, it seemed like a dream that someone would pay her to bond with patrons over the love of books. (His favorite of hers is “The Great Gatsby”).

“Readers are different,” he said. “They are thinkers.”

The store eventually moved to its current location, and after Carlson's death, the owner's husband offered to sell it to Kropp, then 60 years old. She bought it in 2006 for about $100,000, drawing from her savings, as well as some of her daughter's and a sum she inherited after her father's death to cover the down payment.

“It’s been a pleasure,” she said of owning the store.

Karen Kropp hands her books to a customer at Book Rack.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

During the first few years, they were often busy and she hired local high school students to help run the store, although she tended it alone most of the time, working 10-hour shifts. Back then, they often generated more than $10,000 in sales a month, but things slowed as customers adapted to the 48-hour click-and-receive model of the Amazon era.

“Everyone loves him.” now,” she said. “And I can't do that.”

In the months before the pandemic, Kropp considered selling the store and moving closer to his children, grandchildren and five great-grandchildren, but decided to wait a little longer.

Then, during lockdowns, sales dropped to almost zero. The bills were still due, as was rent for the store and the fee for a storage unit where he kept excess books, which together cost about $2,000 a month.

Karen Kropp calls a customer at Book Rack during a liquidation sale before the store closes.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Sales eventually increased again, but never fully recovered; Now, she said, it sometimes takes two days before sales reach $200.

After the toughest times, there was always a bright spark: a busy week, a special interaction between clients. After one of those sparks in late 2022, she cashed in on her $50,000 life insurance policy and received only $5,000 even though she had paid $18,000.

The payment was allocated to bills, rent and payroll. For the first time in 20 years, his passion began to feel like work. She realized that he had left no part of himself for her: every free second and thought had gone to the store.

It was time.

On a recent morning, Kropp was sitting behind the counter, next to a gift basket of peanut M&Ms left by a customer and stacks of books she planned to donate if they didn't sell before the official closing date of Feb. 28. She has a personal policy: no book ends up in the trash unless it has mold or there is evidence that an animal has been living inside.)

A man leaning on a cane walked through the door and she greeted him.

“Wow, I'm sorry to hear you're leaving,” he said.

“Yes,” she said, nodding.

As was often the case, the books triggered memories and he began to tell her how, when he was 20, he traveled around California in a camper reading novels by the mystery writer John D. MacDonald. He was looking for one of his books called “The Long Lavender Look”.

Kropp nodded and his friend Peter Tran, who sometimes volunteers at the store, headed to the back of the store and quickly located a yellowed copy. With the clearance sale discount, the customer paid $1.10 for the paperback.

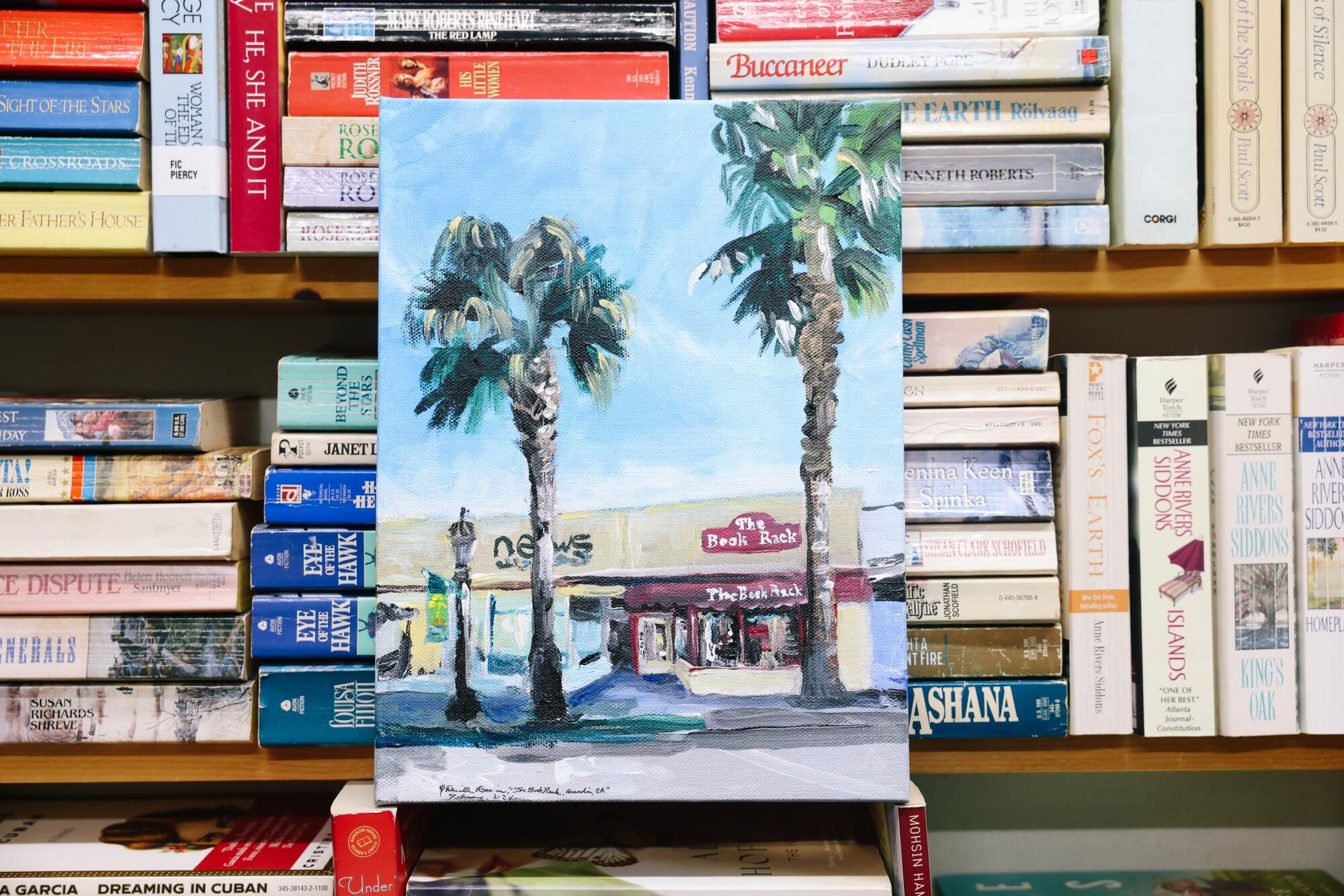

A longtime customer, whose artwork used to line the walls of the Book Rack, gave Kropp a painting of the display window.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Danielle Rosaria Nahas, a customer who lives down the street, came in with her daughter. Nahas, an artist, carried a window painting she had done for Kropp.

“Thank you, honey,” Kropp said, his emerald eyes wet with tears. “This is beautiful.”

Nahas had written the family's address on the back of the wooden frame.

“So if you ever miss us,” he said, “you can write to us.”

Nahas has no family in the area, she said, and her children came to consider Kropp like a grandmother. Her family created a home library with books from the store during the pandemic, and Kropp, she said, had always made her and her daughter, Amy Rose, 8, who has autism, feel very welcome.

The girl ran towards the children's section, spinning around.

“Books, books, read,” he said out loud.

A few minutes later a woman arrived with a list of several titles. She was putting together an auction item with a t-shirt that said “I'm with the Banned,” as well as some commonly banned books.

Karen Kropp looks for a book for a customer at Book Rack.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Kropp squinted at the list and noticed that it didn't include the names of the authors, which is how the store is organized. He closed his eyes for a moment, conjuring up a name.

“Oh, Cisneros!” she said to herself, as she walked to get a copy of “The House on Mango Street.”

“My brain has always been my computer,” he said.

After the customer left, the store fell silent and Kropp and Tran reminisced about the past. Then they fell silent too.

“The end of the chapter,” he said quietly.

“But,” Kropp said, smiling, “it was a long chapter.”