I don't know what I expected from Barbara Lee when an assistant handed her the phone, but the laughter I heard certainly wasn't the right one.

Only a few hours had passed since the veteran Oakland congresswoman issued a statement acknowledging the U.S. Senate primary and congratulating her Democratic colleague, Rep. Adam B. Schiff of Burbank.

Lee came in fourth, more than a million votes behind Schiff and Republican Steve Garvey, and hundreds of thousands of votes behind Democratic Rep. Katie Porter of Irvine, who came in third. Votes are still being counted, but the Senate race was called minutes after polls closed on Super Tuesday.

It was, by any stretch of the imagination, a crushing defeat.

Especially since Lee, and a committed brotherhood of politicians, activists, academics and lobbyists from across California, had spent nearly four years working behind the scenes to boost the representation of black women at the highest levels of the federal government.

Now Schiff and Garvey will face off in the November general election, and Schiff will certainly win in this overwhelmingly Democratic state. He will be a senator for many years.

Then I asked myself, why was Lee laughing?

“I have been persistent and every step of the way there have been obstacles and obstacles,” she told me, growing more serious. “But again, this is a great example of a black woman's life.”

::

It is worth reflecting on how we got here. At least, that's what California Secretary of State Shirley Weber has been doing.

“It all started with the belief that African Americans deserve to have a seat,” he told me.

It was 2020, and Weber was serving in the state Assembly and as leader of the Legislative Black Caucus. Joe Biden had just been elected president, with no little help from Black women, and Kamala Harris had just vacated her Senate seat to become the country's first Black and South Asian vice president.

Weber and a long list of black politicians, activists, academics, and lobbyists decided that black women should continue to have representation in the upper house. That it would be a loss not to have someone with such intersectional life experiences when the state and country become more diverse with each passing year.

“The ability across the country to recognize and support Black women in state positions is very bleak,” Weber told me in 2020. “You have 100 people in the Senate and you don't have a single Black woman.”

Thus the “Keep Your Seat” campaign was born and the words became a rallying cry. His supporters urged Gov. Gavin Newsom to do just that by choosing Lee or then-Rep. Karen Bass, both eminently qualified veteran legislators, as Harris' successor.

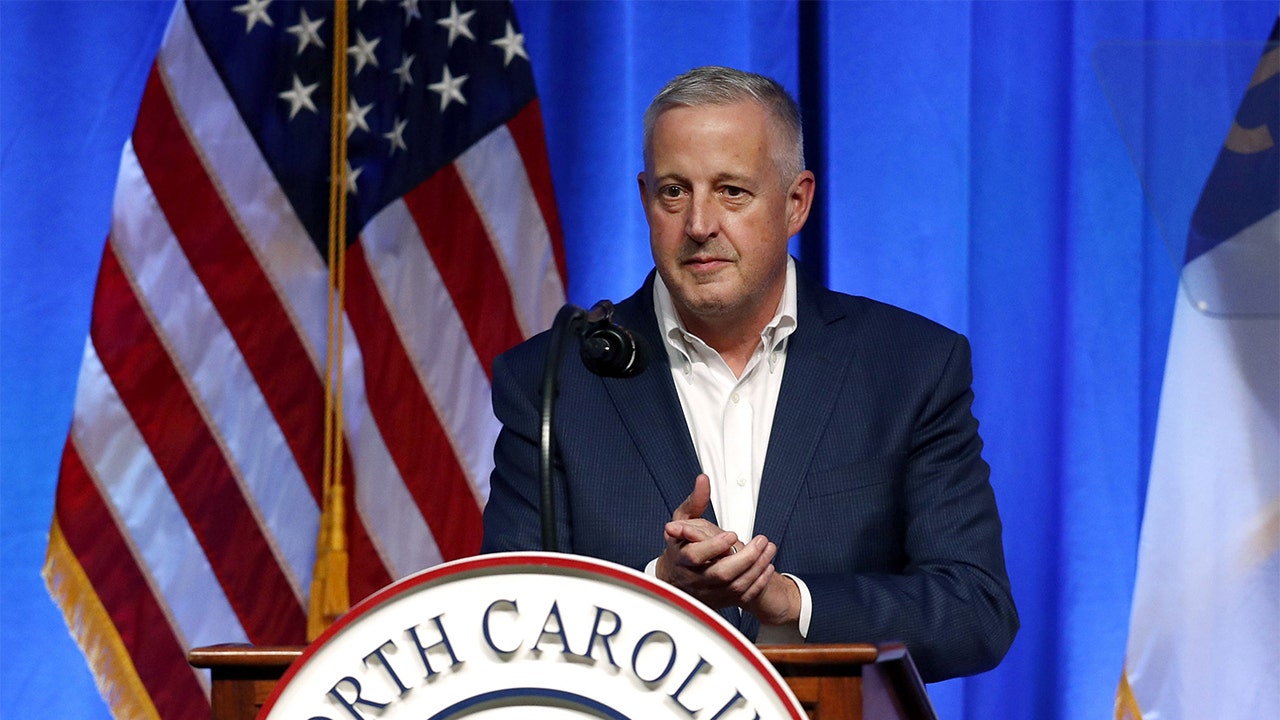

Lee, in Santa Rosa last month, maintained his progressive stances and “Hold the Seat” message as he campaigned for Senate in California cities and counties.

(Josh Edelson / for The Times)

Newsom ended up selecting then-Secretary of State Alex Padilla, Lee remained in Congress, and Bass, of course, became mayor of Los Angeles. But the war cry did not remain silent. Rather, he returned alongside calls for Sen. Dianne Feinstein to resign over concerns about her health, prompting Newsom to promise to appoint a Black woman to her seat if necessary.

Then Feinstein died last year, setting off a days-long political disaster, largely of the governor's own making. What was at stake was an apparent caveat in Newsom's promise. He said he would make an “interim appointment” because the campaign for the Senate seat had already been underway for months.

Lee and other black women, myself included, were offended and wondered why we were only good enough to be caretakers for Schiff, who even then was in charge. Newsom said his words were being misinterpreted and he resisted calls to name Lee directly.

In the end, the governor appointed his political ally Laphonza Butler, the black woman who led Emily's List, and she ultimately decided not to run for a full term.

Given all that back-and-forth, Weber was surprised that Lee continued his Senate campaign and resigned his House seat. This is especially true because even without Lee, the Senate is likely to gain another Black woman in November, as Angela Alsobrooks of Maryland and Lisa Blunt Rochester of Delaware are also running for seats.

Some people, watching the polls, had been quietly pressuring Lee to drop out of school.

“But that's Barbara, you know? “She does what she believes in and you can never question her heart,” Weber told me. “Another person would have been calculating, 'Well, if I run and lose, it's going to be this versus that.' And then she didn't calculate like that. “She decided we needed to have a black woman in that seat.”

::

I doubt Lee will ever admit it, but he had to know he was probably going to lose.

For months, polls showed her consistently trailing her opponents, even after receiving a plurality of votes from delegates at the California Democratic Party convention. Many of those delegates, like voters in their Bay Area district, tended to lean more progressive than voters in other parts of the state.

Lee also lacked a state profile, unlike Schiff, whose prominence rose by leading the first impeachment trial of Donald Trump; or Porter with his notes on the whiteboard during congressional hearings; or even Garvey, with his star spins against the Dodgers and Padres.

Perhaps even more important is that Lee did not have tens of millions of dollars to buy a state profile with a television advertising campaign. Before deciding to run for the Senate, the 77-year-old had never needed a sophisticated fundraising operation and had fiercely protected her private life rather than spreading it on social media to boost her popularity.

“If you don't have money coming from everywhere,” he acknowledged, “it's very difficult to get in front of voters.”

So while Lee's campaign only raised about $5 million, according to the latest filings with the Federal Election Commission, he was up against two of the most prolific fundraisers in Congress. Both Schiff and Porter amassed war chests approaching $30 million, with Schiff, blessed by the Democratic Party establishment, long at the helm.

Which is why it's ridiculous that, of all the candidates, it was Porter (with roughly as much money in his campaign account as Lee had raised during his entire campaign) who decided to complain about the influence of money in politics.

“Thanks to you,” he posted to his followers on It was a terrible choice of words because, of course, the election was not “rigged.” No ballots were illegally tampered with.

But it is true that our political system is “rigged” in the sense that social prejudices and structural inequalities often work against women and people of color who run for public office. This has been confirmed in study after study, including a recent one from the Pew Research Center.

We don't have an excessive number of white men in elected office because most white men are political geniuses and most women and people of color are terrible candidates. We do this because women of color, in particular, are finding it increasingly difficult to raise money because they have less access to high-level donors and therefore find it more difficult to get elected.

“That's a reality when you're in a poor community, and you've just been a regular activist and you work hard in your community and you deliver,” Weber said. “You're not in a circle that raises $30 million.”

Lee, a leftist, stayed in the race despite problems including systemic fundraising challenges and low polls against her higher-profile rivals, Adam B. Schiff, Katie Porter and Steve Garvey, a leftist in a debate in January.

(Damián Dovarganes / Associated Press)

But Lee's decision to run despite these challenges is what she says inspired many of the people she met on the campaign trail, including numerous Black women who were organizing fledgling campaigns to run for office.

They would exchange stories about the difficulties ahead. Racism and sexism embedded in the system.

“A lot of them would come up and whisper to me, 'I know what the deal is.' “It’s a common conversation that black women have,” Lee told me. “When you go out and do something that others didn't think you should do as a black woman, you get a lot of backlash.”

I also saw. At his campaign events in cities and counties where he had never before had a reason to spend much time, black women and people of color hung on Lee's every word:

How she found the courage to travel to Mexico to get an abortion as a teenager. How he worked with the Black Panthers. How, as a member of Congress, she was among the first to call for a permanent ceasefire in Gaza and the only one to resist the war after 9/11.

Before running for the Senate, Lee was unknown to many. He is now an underrated heroine with a cult following.

Therefore, I agree with Weber when he says that Lee's loss in the primary does not diminish the fight for representation that began with the “Keep the Seat” campaign. Or even the pressure to get Harris elected to the Senate in the first place.

“No one is saying we shouldn't do this again. Nobody seems to say, “Well, we missed our chance.” We missed our shot,'” Weber said. “But a lot of women I've talked to more recently have said, 'When this is over, we're going to have to organize.'”

Raising money will always be a problem. So will racism and sexism. But in the end, the Senate campaign might have been more important than the election. And, just like that, it's Lee who has the last laugh.