Joshua Meyrowitz took the stage at the Laugh Factory in Hollywood and introduced himself to the crowd as “your autistic partner,” prompting cheers and applause.

“One of the hardest things for an autistic person is being able to relate to people,” the comedian said, “and as a comedian, you're… requested Connecting with people.

“With an audience full of autistic people, I don’t have to identify with anything!” Meyrowitz declared as laughter spread through the room. “I’m in the zone, bro!”

It was a Wednesday night at the historic Sunset Boulevard club, and in many ways the show unfolding on its brightly lit stage sounded like any other comedy show on the Sunset Strip, with one-liners about pictures of genitals, politics, married life and the more unpleasant side effects of Ozempic.

But his goal was ambitious: to make the noisy world of stand-up comedy a welcoming place for people whose brains work differently. This show played to a crowd full of autistic adults and other neurodivergent people, many of them accompanied by their neurotypical family members and friends.

The changes made to a typical show were small: a “chill-out space” for anyone who needed to step outside for a break, turning down the volume of the music playing inside and avoiding sudden, loud changes in music between acts, and warning comedians to stop if anyone jumped up or said something without thinking.

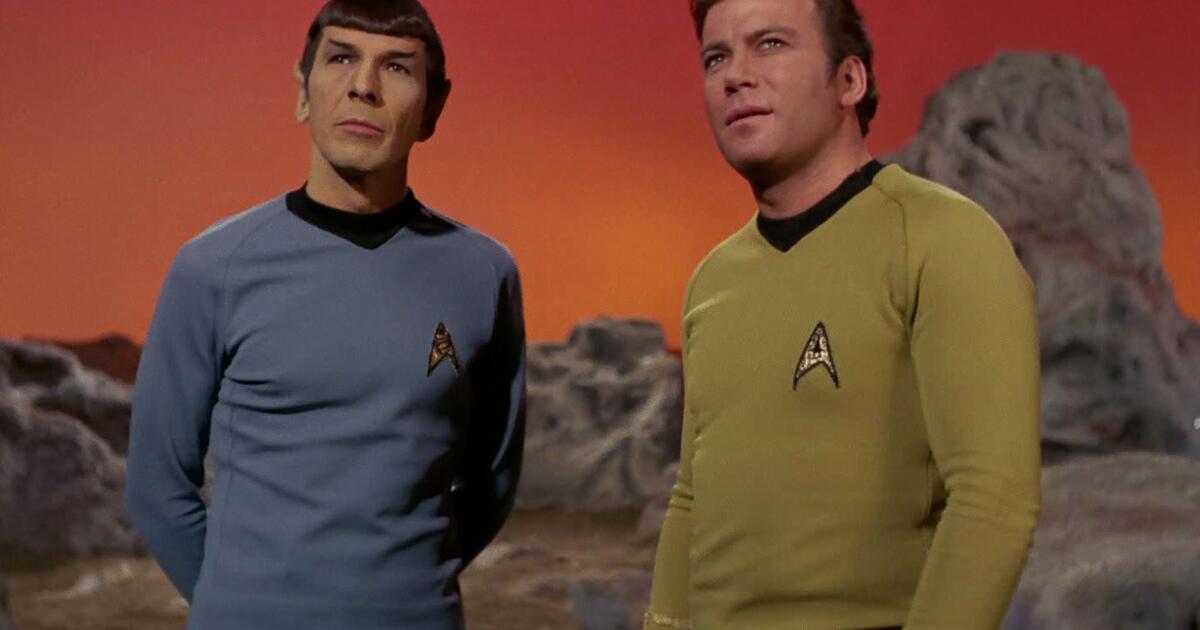

Comedian Jeremiah Watkins performs at the Laugh Factory.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

Interestingly, making a comedy show inclusive of neurodivergent people “isn't a huge shift at all; it's something that no one had thought of doing,” said Rob Kutner, a comedy writer and co-producer of the Wednesday show.

“You don't need much, except a little consideration.”

When Jeremiah Watkins heard someone in the audience interrupt and say, “What about trains?” the comedian took the opportunity to do an ad-lib.

“That about “Trains?” he replied enthusiastically. “Are you a fan of trains? Good. What is your favorite type of train?” he asked before launching into his next part.

Months earlier, at a smaller comedy show for an autistic audience, Watkins recalled surprising an audience member who quoted a “Harry Potter” line to him by responding with an imitation of Professor Severus Snape.

Wednesday’s show, called “Let It Out,” can be a model for comedy acts around the world, Kutner and co-producer Mike Rotman said. The pair worked with activists like Autism in Entertainment, which promotes employment of people on the autism spectrum in the industry, to publicize and document the show.

What they want people to know is that inclusion can be easy. “This should be normalized,” Rotman said. “This should be a weekly occurrence.”

Willie Hunter laughs as he hosts “Let It Out,” a comedy show that aimed to be inclusive of neurodivergent people.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

As increasing numbers of Americans are diagnosed with autism (a condition that can shape how people think, relate to others and experience the world) and generations have grown up with the protections of the Americans with Disabilities Act, there has been a steady push for inclusion in daily life.

Many public spaces have taken steps to better accommodate neurodivergent people and their sensory needs: some movie theaters offer “sensory-friendly” screenings where the lights stay on and the sound is softened. Museums may have designated days and times when fewer people are allowed in to limit crowding.

Still, Maja Watkins, whose work focuses on teaching social and emotional skills, says there is still a shortage of fun, accessible options tailored to autistic adults.

“You’re in high school. You go to prom and a lot of times the special education department offers you fun opportunities. And then you graduate and little by little the services and programs start to get cut,” Watkins said.

Her husband is a comedian (the same one who referenced trains that Wednesday night), and she said her 38-year-old brother, who has autism, loves comedy shows but is sometimes put off by loud noise or late hours.

“How cool would it be if it was a comedy show that made everyone laugh… but maybe the seating was arranged so that people weren’t so packed in?” Maja Watkins said. “Maybe it wouldn’t be too loud at the beginning? Maybe if someone needed to pull out a Fidget… to be quieter, then that’s fine.”

Or being able to get up and take a break without having to face a barb from someone on stage: “That's what my brother would have needed to stay through the whole show,” he said.

Kole Spickler gives an interview backstage at Laugh Factory.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

Among Wednesday’s attendees were young people taking a class at Miracle Project, a Los Angeles-based organization that teaches social skills through improvisation. Teacher Sandy Abramson said that for her students, “going to a place like this can be overwhelming because you have to conform to the social norm, which is, ‘Don’t talk. You can’t take breaks.’ Things like that.”

In this show, she said, “you don’t have to feel nervous or anxious about how you’ll be perceived.”

Kole Spickler, 23, was excited about the start of the show. “I like being in the audience,” said Spickler, who is autistic and counts Jim Gaffigan and Brian Regan among his favorite comedians.

Like many autistic people, he can be blunt, sometimes humorously so. When asked what he was learning in social skills class (with a Miracle Project staff member standing by), he said, “I'm not sure if I really learned anything.”

Had he enjoyed it?

“Yeah, sort of,” he said. “Some of my peers can be really annoying.”

During the show, the audience was treated to jokes about autism. “I was born with autism, but everything else is my parents’ fault,” Meyrowitz joked. Kruger Dunn told the audience that he had been diagnosed with autism late in life.

Bryan Miguel attends a comedy show at the Laugh Factory.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

Doctors had told her, “You don’t lie. You like to memorize a lot of facts and you don’t ask for help even if there are problems,” Dunn said. “I said, ‘So what you’re saying is that I’m trustworthy, I’m smart and I’m not a snitch?’”

“You use the word ‘disability’ a lot, but to me those are abilities, Doc,” Dunn said to laughter and applause.

But Maja Watkins and others involved in organizing the show at the Laugh Factory stressed that pleasing the crowd didn't mean doing a comedy show only about autism, or ditching their usual jokes. Rotman said some comedians had asked her, “Are you looking for me to do neurodivergent material?”

“Not at all,” he told them. “Do your set… Do your seven minutes.”

Laugh Factory host Carmella Rogers said she insisted on working that Wednesday night after hearing about the show because she “wouldn't have to wear a mask like I normally would” to appear neurotypical to showgoers.

Her job involves “showing a lot of emotion, being really happy all the time,” which can sometimes be difficult for Rogers, who is autistic and has attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. In a break between shows that night, she said she was pleased that the comedians hadn’t infantilized the neurodivergent crowd.

“People tend to think that if you are autistic, you should be treated like a child,” he said. “I am like a normal adult, there are just certain things about me that make me different from the average person.”

Comedian Laurie Kilmartin performs during “Let It Out” at the Laugh Factory.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

Before her performance, comedian Laurie Kilmartin said she was “basically doing a normal show” but didn't react the way she would if someone in the audience raised their voice.

“I've done every hellish gig in the world, so I'm not easily swayed,” Kilmartin said, before hastening to add: “I'm not implying this is a hellish gig, I'm just saying!”

At first glance, stand-up may seem like an unexpected place for autistic people, who can ignore social cues or communicate in ways that normal people struggle to understand. But it has often been a refuge for people who don't fit into the norm.

Meyrowitz, who has been acting for more than a decade and a half, said her anxiety made it difficult for her to work “normal jobs,” but in comedy, “we’re all a bunch of weirdos.” She once thought she would live with her parents her entire life. Now she shares an apartment with other comedians.

Comedy, Meyrowitz said, “gives me a community of friends I never had before.”