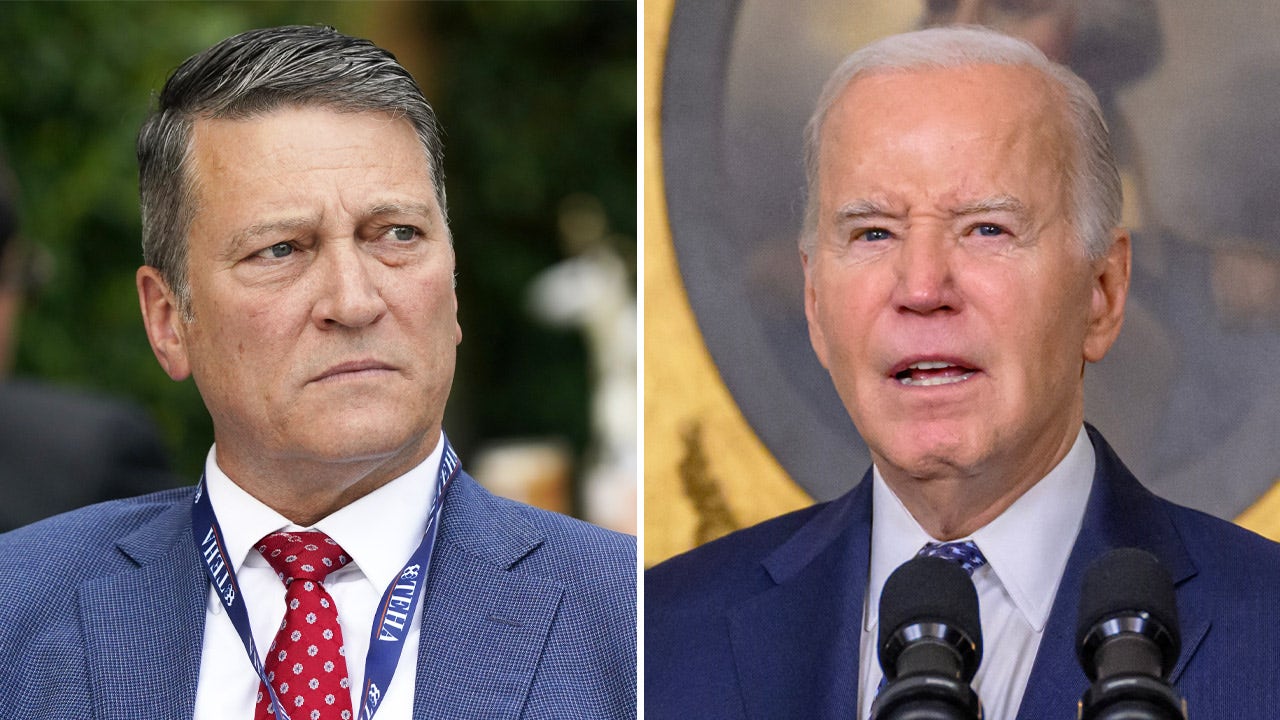

A top aide to Los Angeles County District Attorney George Gascón pleaded not guilty Thursday after state prosecutors said she illegally used confidential personnel records three years ago when she flagged the names of several sheriff's deputies for possible inclusion on a list of problem officers.

The attorney representing Diana Teran argued in court that the charges against her did not constitute a crime because maintaining a list of officers accused of misconduct was part of her job overseeing the district attorney's ethics and integrity operations.

“This is just a matter of common sense,” Teran’s attorney, James Spertus, said in court. “Is it a crime to do your job internally at the county attorney’s office when you have information in your head?”

California Department of Justice prosecutors said it was too early in the legal process to address those details. For now, the state said, the two sides could only discuss the content of the criminal complaint filed against them, not the other documents used to support it.

After hearing several hours of legal arguments, Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Charlaine Olmedo sided with the state and moved forward with Teran's arraignment.

On Thursday, the judge also denied requests — from an attorney for the Los Angeles Public Press news site — to release documents that could show that the officers’ records were already public. Releasing those documents, Olmedo said, could violate an existing protective order.

Attorney General Rob Bonta filed the criminal complaint against Teran in April, and the allegations at the center of the politically charged case date back to 2018, when she worked at the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department as a police constitutional counsel. Part of her duties there included accessing confidential officer records and internal affairs investigations.

The department's secret tracking software kept records of the more than 1,600 personnel files it searched and reviewed, according to an affidavit state prosecutors filed in court this year.

After leaving the Sheriff's Department, Teran joined the district attorney's office. It's unclear what his current status is, but a spokesperson for the office previously said he no longer oversaw ethics and integrity operations.

According to state prosecutors, while working in the district attorney’s office in 2021, Teran sent a list of 33 names and supporting documents to a fellow deputy district attorney for possible inclusion in the so-called Brady database, which contains officers with problematic disciplinary histories. The name is a reference to a landmark 1963 U.S. Supreme Court decision requiring prosecutors to turn over any evidence favorable to a defendant, including evidence of police misconduct.

The affidavit says several of the names Teran emailed to fellow prosecutor Pamela Revel were of deputies whose files he had accessed while working at the Sheriff’s Department. Eleven of them had not been mentioned in news stories or public records, so he allegedly would not have been able to identify them otherwise, state prosecutors said.

After fighting for more than two months to obtain the affidavit revealing the names of the 11 officers, Spertus earlier this month submitted hundreds of pages of documents that he said showed his disciplinary records were already public in court records and news articles.

“From the moment this case was presented, I suspected what the motive was. [for filing it] “It was because there was no crime and the release of the affidavit confirms that,” Spertus said at the time. “The underlying theory is that she stole public information.”

On Thursday, Susan Seager, the attorney representing LA Public Press, argued that hundreds of pages of documents Spertus submitted should be made public. The judge disagreed, saying the only reason Spertus knew to look up the names of certain agents and find those records was because he had access to protected information.

“It’s disappointing that the high court has not recognized that these are public court records and they should be disclosed and shown to the public,” Seager told the Times after court on Thursday. “If the Justice Department is criminally prosecuting a prosecutor for using public records, that seems to suggest that anyone who uses public records to investigate misbehaving sheriff’s deputies is subject to criminal prosecution.”

Olmedo decided that at this stage the court could only rely on information contained in the “four cardinal points” of the criminal complaint. After accepting Teran’s guilty plea, Olmedo set a preliminary hearing for August 7.