This story is part of December Image. Revelry theme, honoring what music does so well: giving people a sense of permission to be themselves unapologetically.

The belt used to belong to his father. Black leather, silver stitching, “RUBEN” written on the side with the initials “RV” on the buckle, for Rubén Vallejo, a name both men share. Now he's wearing it on the younger Vallejo's waist as he prepares for a night out at the Pico Rivera Sports Arena, a place he's been “more than 50 times,” he says, but this one is special. He puts on his second-hand button-down shirt, adjusts his belt buckle, and looks in the mirror.

For the Vallejo family, the ring is a second home and dancing there is a tradition. It stands as a cultural landmark for Los Angeles' Mexican community and hosts decades of concerts, rodeos and community celebrations. Vallejo's parents began attending in the early '90s, when the band and corridos began to resonate in Los Angeles. Tonight, the beloved singer Pancho Barraza performs and Vallejo will go with his mother, his sister, his aunt and his godmother.

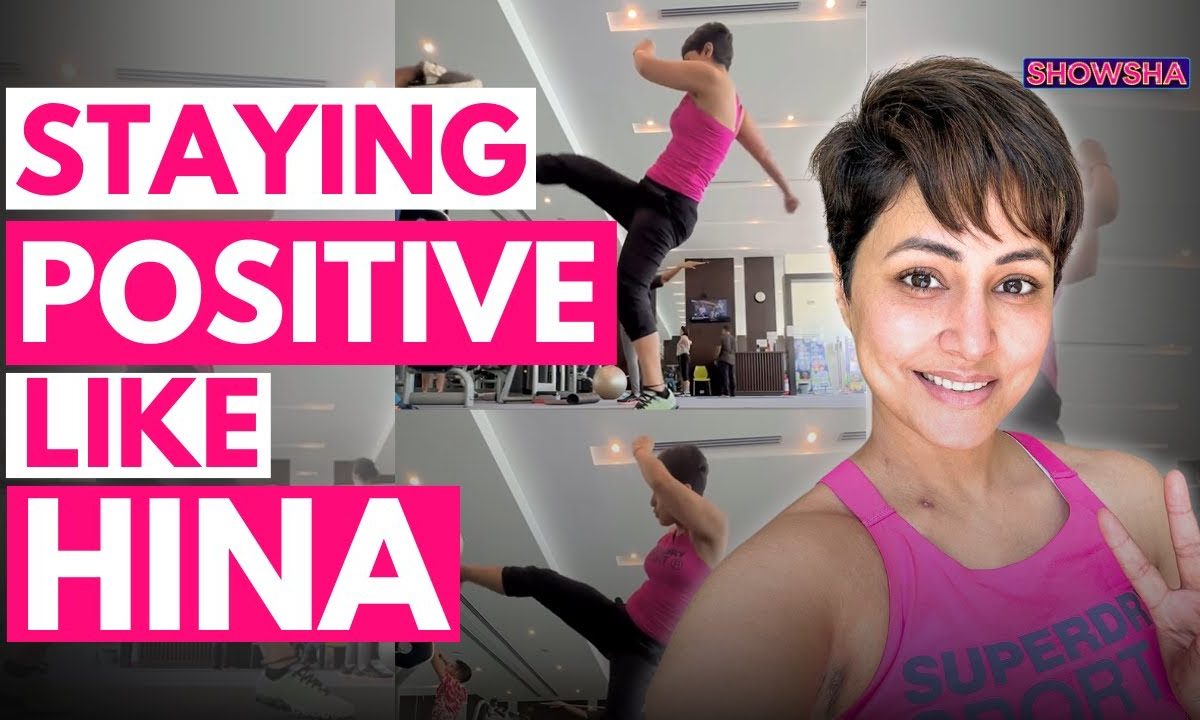

Vallejo wears a black Texan from Márquez Clásico, a second-hand cowboy-style button-down shirt, second-hand jeans, and a belt inherited from his father.

At 22 years old, Vallejo doesn't see regional Mexican music as nostalgia: it's simply who he is, something he wears, dances to, and claims as his own. “I want to revive this and let other people know that this art and culture is still alive,” Vallejo says. “The way I dress, the music I listen to, I want everyone to know that kids like this.”

It's just after 6:30 p.m. on a Sunday in late October, and the sound of a live band drifts in from a small Mexican restaurant near the Vallejo family home in Mid-City as excitement builds for the evening. Horns and drums spill into the street as the neighborhood celebrates the first Day of the Dead festivities. Inside, Vallejo opens the door to her fairytale bungalow, where her parents lounge in the living room. But it is his bedroom that tells you who he is: a space that looks like a paisa museum.

On the wall of the closet hang second-hand padded banda jackets: Banda Recodo, Banda Machos, El Coyote y su Banda Tierra Santa. Stacks of CDs and cassettes line his dresser, from Banda El Limón to Banda Móvil and a signed Pepe Aguilar. On one wall, a small black-and-white watercolor by Chalino Sánchez that he painted himself hangs next to a framed jersey from the 1998 Mexico World Cup. “It all started with my grandfather,” Vallejo says. “I was a trombone player and played in a band in my mother's hometown in Jalisco.”

Music runs in the family. His uncles formed a group called Banda La Movida, and Vallejo still teaches acoustic guitar on his own when he's not apprenticing as a hat maker at Márquez Clásico, making tejanas and charro hats.

“I feel like being an old soul gives people a sense of how things used to be in the past,” he says of the intergenerational bridge between his work and his personal interests. “That connection is something very necessary right now.”

Beyond the band's memories, the real story lives in old family photos: snapshots of backyard parties, their parents dressed in '90s cowboy style in Los Angeles parking lots, and a large framed portrait of their Banda La Movida uncles, posing in blue jackets and matching white jeans.

“This is a photo of us in the [Pico Rivera Sports Arena] parking lot. We would go support my cousins in a battle of the bands. Which also meant fan clubs against fan clubs. The pants were much wider then,” Vallejo's mother, María Aracely, explains in Spanish.

The belt used to belong to his father. Black leather, silver stitching, “RUBEN” written on the side with the initials “RV” on the buckle, for Rubén Vallejo, a name both men share.

Vallejo's look for the evening is simple but intentional: a black pair of jeans from Márquez Clásico, a second-hand black-and-white cowboy-style button-down shirt printed with deer silhouettes, loose “elephant pants,” as he calls them, his father's brown snakeskin boots, and, of course, the embroidered belt that ties it all together.

“This is very Pancho Barraza-esque, especially with the deer shirt. I looked up old videos of him performing on YouTube. I do it a lot with these older band looks,” Vallejo says.

A rustic leather handkerchief embroidered with “Banda La Movida” sewn vertically hangs from his left pocket, a souvenir his mother kept from his group of siblings in the past.

“I feel like being an old soul gives people a sense of how things used to be in the past. That connection is a very necessary thing right now.”

Elegantly late, Vallejo arrives at Barraza's concert with less than an hour to spare, but he doesn't seem bothered. His mom and older sister, Jennifer, are there, along with his aunt and godmother. A mixture of mud and alcohol hangs in the air as the family makes their way across the artificial grass tarps that cover the lower level of the arena. Barraza is on stage with a mariachi accompanying his band. With the amount of people still drinking and dancing, it's hard to believe it's past 10 o'clock on a Sunday night.

Passing by the stands, Vallejo's mother is amazed as she points to a certain section of the upper level of the arena and remembers the number of times she sat there and watched countless bands before she had Ruben and his sister. As the concert nears its end, Barraza closes with one of Vallejo's favorite songs, “Mi Enemigo El Amor,” which Vallejo sings at the top of his lungs, jokingly and heartbroken.

“I hadn't seen it live yet and the atmosphere here feels great because everyone here is connected to the music. Even though we're in Los Angeles, I feel at home, like in Mexico.”

Frank X. Rojas is a Los Angeles native who writes about culture, style, and the people who shape his city. Their stories live in the quiet details that define Los Angeles.

Photography assistant Jonathan Chacon