“This is where all the cruises happened.”

Jonathan Bailey and I are in Pershing Square on a bright, blustery spring afternoon, nearing the end of a DIY tour of downtown L.A.'s queer history: One Magazine, Cooper Do-Nuts/Nancy Valverde Square, the Bathhouse Dover, the Biltmore Hotel and this, the city's old Central Park, a refuge, since before the First World War, for “fairies” and “ladybugs”, soldiers on leave and beatniks on the road.

“Is it still happening now?” he asks.

“Probably not that much,” I venture.

“Well, let me know if it's happening,” he jokes, a mischievous smile lighting up his face.

Bailey understands the uses of the charm offensive. As Sam, the handsome Lothario from Phoebe Waller-Bridge's charming pre-“Fleabag” curiosity, “Crashing”; Anthony, the romantic hero of the second season of “Bridgerton”; and John, the idiot protagonist of Mike Bartlett's love triangle play “Cock,” the 36-year-old English actor has strutted to the precipice of stardom. With big studio roles like “Wicked” and “Jurassic World” on the horizon, he may break through. However, he delivers the best work of his career in Showtime's queer melodrama “Fellow Travelers,” as Tim Laughlin, an anti-communist crusader turned gay rights activist, leaving behind the self-assured libertines and taking advantage a new source: soft power.

Tim may be, as Bailey puts it, “an open nerve,” but he turns out to be a devout Catholic and political naïve, who falls for smooth State Department agent Hawkins “Hawk” Fuller (Matt Bomer), as does the Senator Joseph McCarthy. him trying to purge the federal government of LGBTQ people, it's really formidable.

From the Lavender Scare to the depths of the AIDS crisis, in scenes of tenderness, cruelty and heart-pounding sex, Bailey's performance communicates that unspoken truth about relationships: it takes more strength to submit than to control. The first requires discipline, courage, confidence; the latter only requires strength.

“In 'Bridgerton,' [Bailey] He's like a Hawkins Fuller character: he's very sexy and he's got a lot of power, he's got that kind of charisma that's definitely not Tim at all,” says “Fellow Travelers” creator Ron Nyswaner.

But any doubts about Bailey's ability to interact with Bomer, who boarded the project early in development, were dispelled by the actors' virtual rehearsal of a meeting on a park bench in the pilot. “'Well, that's the first time,'” Nyswaner recalls an executive texting him. “I cried during a chemistry lecture.”

'Am I inviting people in?'

Bailey grew up in a family of musicians in the Oxfordshire countryside outside London, and this, along with an appreciation for the morning prayers, choir practices and mass he attended as a scholarship student at the local Catholic school , fueled his precocious talents. (“I loved the performance,” she laughs. “Not to diminish the celebration of the religious process, but I did love the idea of wearing a dress.”) By age 10, he had appeared on the West End, playing Gavroche in a production of “Les Miserables,” an experience he now recognizes as an encounter with a queer family, albeit one overshadowed by the cost of the AIDS crisis, which reached its peak. peak in the UK in the mid-1990s.

Jonathan Bailey, lying on his back, and Matt Bomer in “Fellow Travelers.”

(Show time)

“When you ask me about my childhood, there's a lot I don't remember, and I think that applies to anyone who's been fighting or fleeing for 20 years,” he says. “I would have been in a cast of people whose friends would have died in the last seven years. I think about where I was seven years ago. I had all my gay friends then. Only in retrospect can I adapt a true gay community around me. [in the theater]I just wasn't aware of [then].”

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, American and British culture presented queer teenagers with a bewildering array of contradictory signals. As celebrity darlings came out in increasing numbers, and the battle for marriage equality became front and center in LGBTQ political organizing, the media continued to propagate harmful stereotypes of gay men as miserable, lonely, perverted or worse, and, Bailey recalls, cruelly turned homosexual. George Michael, arrested on suspicion of cruising in a Beverly Hills bathroom in 1998, and Irish pop star Stephen Gately, who revealed his sexuality in 1999, fearing he was about to be discovered, in tabloid shows .

It's no surprise that Bailey, like many LGBTQ people of her generation, felt the “chemical” thrill of “validation and acceptance” during London Pride at age 18 and then embarked on a two-year relationship with a woman. about 20 years old.

“It's dangerous that if you're not exposed to people who can show you other examples of happiness, you think that's the easiest way to live,” Bailey says. “It's funny. You look back and you can tell the story one way, which is that I always knew who I was and my sexuality and my identity within that. But obviously it was very difficult at times. I compromised my own happiness, for sure. And it compromised the happiness of other people.”

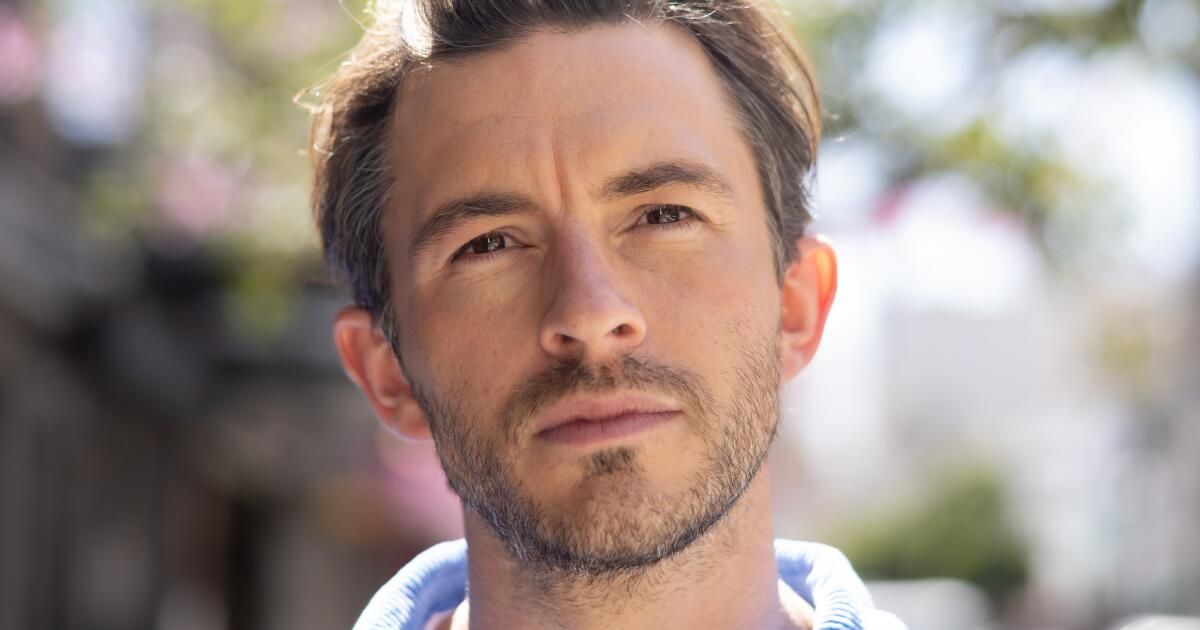

Bailey says the experience of playing anti-communist crusader-turned-gay rights activist Tim Laughlin in “Fellow Travelers” launched his thinking about his own legacy: “What do I want to leave behind?”

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

Revelations about his personal life have become particularly thorny for the actor since the release of “Bridgerton,” the hit film from executive producer Shonda Rhimes.

“The Netflix effect completely throws you off,” he says, recalling the experience of finding a paparazzo waiting outside his new apartment before he even moved in. “Suddenly, you start having nightmares about people climbing through your windows. .. Even now, talking about it makes me feel: 'Am I inviting people in?'”

He also criticizes the media for producing headlines about the smallest details of celebrities' private lives, often disconnected from their original context. In an interview with the London Evening Standard published in December, Bailey described a harrowing encounter in a Washington, D.C., coffee shop in which a man threatened his life for being gay and, in recounting the experience, mentioned in passing the “lovely man.” ”. he had called, shocked, after it happened. While Bailey acknowledges that the original story tackled the topic with aplomb, he was dismayed that more attention wasn't paid to the intended warning about rising anti-LGBTQ sentiment: “The only thing that was distributed in that story was that she had a boyfriend. , and it wasn't true,” he sighs. “It was a bit depressing, if I'm honest.”

Still, Bailey, who once turned down a role in a queer-themed television series because it would have required him to accelerate revelations about his personal life that he wasn't ready to make, is prepared to embrace the power of vulnerability when it fuels the work. . Although a member of his inner circle expressed doubts about the steamy sex scenes in “Companions Traveler,” for example, the actor sensed that they were what made the project worthwhile: “I was like, 'I'm telling you. , they are the reason why this is going to be brilliant.'”

'He has changed the trajectory of my own life'

For those who complain about the state of sex in film and television, “Travel Companions” is the perfect answer. Everything matters, from Tim's first flirtation with Hawk to the final minutes of the finale, because the series, at its core, is about the importance of soft power: the strength needed to bend, but not break; adapt, but not abandon; survive without being reduced to nothing in the process. And representing that through sex, specifically gay sex, makes “travel companions” truly radical.

Bailey understands that revealing so much comes with certain risks. When I tell him that research for the story has filled my algorithmic “For You” feed on co-stars alike. It has long been part of the Hollywood fantasy. But he resents the implication that he and Bomer are anything but skilled actors at work.

“I would love for people to know that the success of our chemistry is not based on us, dammit. In reality, it is about us getting closer to the craft,” she says. “It is a vulnerable situation, talking about it officially. I don't want to rob people of their thoughts. But I have a series of values and, as an artist, it is not necessary to be screwed to tell that love story.”

Behind that craft, Bailey adds, is the confidence to speak, like in a scene from “Fellow Travelers” that was adjusted because he said, “I don't want to be naked today.” He learned to use his voice the hard way: When he was in his early 20s, he recalls, he was once “bullied” on set when “someone was threatened” by him and he promised himself: “I will never do that to them.” tosomeone”. . “I will never allow that to happen.”

“The Netflix effect completely throws you off track,” Bailey says when asked how “Bridgerton” changed her relationship with fame.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

This impulse to direct his influence in support of others has flourished even more with “Companions of Travelers.” On the day of our interview, Bailey enthuses about an upcoming meeting with legendary gay rights activist Cleve Jones and shares his idea for a docu-series chronicling the stories of seniors in the LGBTQ+ community while they're still here to tell them. She describes lying in a hospital bed on the set of World AIDS Day, in character as Tim, surrounded by gay men who had lost friends and lovers during the crisis, and finding himself thinking, “What do I want to leave behind?” .

“I think it's changed the trajectory of my own life,” Bailey says.

This is perhaps the most common reaction I know when delving into queer history: the realization that we, like our forerunners, are responsible for shaping the queer future, whether in politics, society, or art . Nobody is going to do it in our name.

As we stand on the nondescript corner that now bears her name, I tell the story of the late queer activist Nancy Valverde, who was repeatedly arrested while studying at barber school in the 1950s on suspicion of “masking” because of her preference. because of short hair and men's clothing, and subsequently successfully challenged her harassment by the police in court.

“What a hero!” Bailey exclaims, marveling at Valverde's bravery. “What's so interesting about power battles is that, ultimately, identity is what gives you the most strength and power in your life, isn't it?

“Because that's something people can't take away from you: who you are and how you express yourself.”