When Frankie Beverly, lead singer of the soul band Maze, passed away this week, I thought of the audience listening to her recordings from a November 1980 night at the Saenger Theater. Her album “Live in New Orleans” captured more than a concert. It captured a turning point in history.

Opinion columnist

Granderson Landing Station

LZ Granderson writes about culture, politics, sports, and navigating life in America.

President Carter had lost his reelection bid just a week earlier. Nearly 60 percent of Orleans Parish, where Beverly was filming, voted for Carter. GDP grew an astonishing 4.6 percent during Carter’s single term, but inflation was 13 percent, as was the poverty rate. His opponent, Ronald Reagan, blamed social programs and welfare recipients for economic woes. When Reagan first used such rhetoric, in his 1966 campaign for governor of California, the “war on poverty” had just begun; the overall poverty rate was 17 percent, but for black Americans in 1965 it was more than 40 percent.

By 1980, Reagan and his party had a clear record of rejecting the war on poverty and those it purported to help. He cut more than $22 billion from social programs in his first two years. And by the time Reagan left the White House, the county's poverty rate had again reached its highest level since — wait for it — 1965.

Listening to it now, I know that in New Orleans in 1980, when Beverly sang “we'll get through these changing times,” she was referring to all of this and the path that lay ahead. Her music was both the calm before the storm and the tool needed to find peace in the midst of it. That's why “Joy and Pain,” the fourth song on the live album, sounds less like an R&B concert and more like a revival.

“Sometimes we go through life and things don’t always go our way,” he begins. “As you get older, you learn to live with the joys and pains of life… Can I have a witness to that?”

As a child, I thought I understood what Beverly was saying in “Joy and Sorrow.” And then, like Beverly said, you get older. And with wiser eyes you are better able to see how painful it must have been for parents not to be able to feed their children or keep the lights on.

When “Live in New Orleans” was released in 1981, nearly 1 in 7 Americans had fallen into poverty, crack cocaine was popping up in major cities and the U.S. divorce rate was at an all-time high. Beverly’s music kept the spirits of the black community high, much as Bruce Springsteen and John Mellencamp became voices for the white working class during that same era.

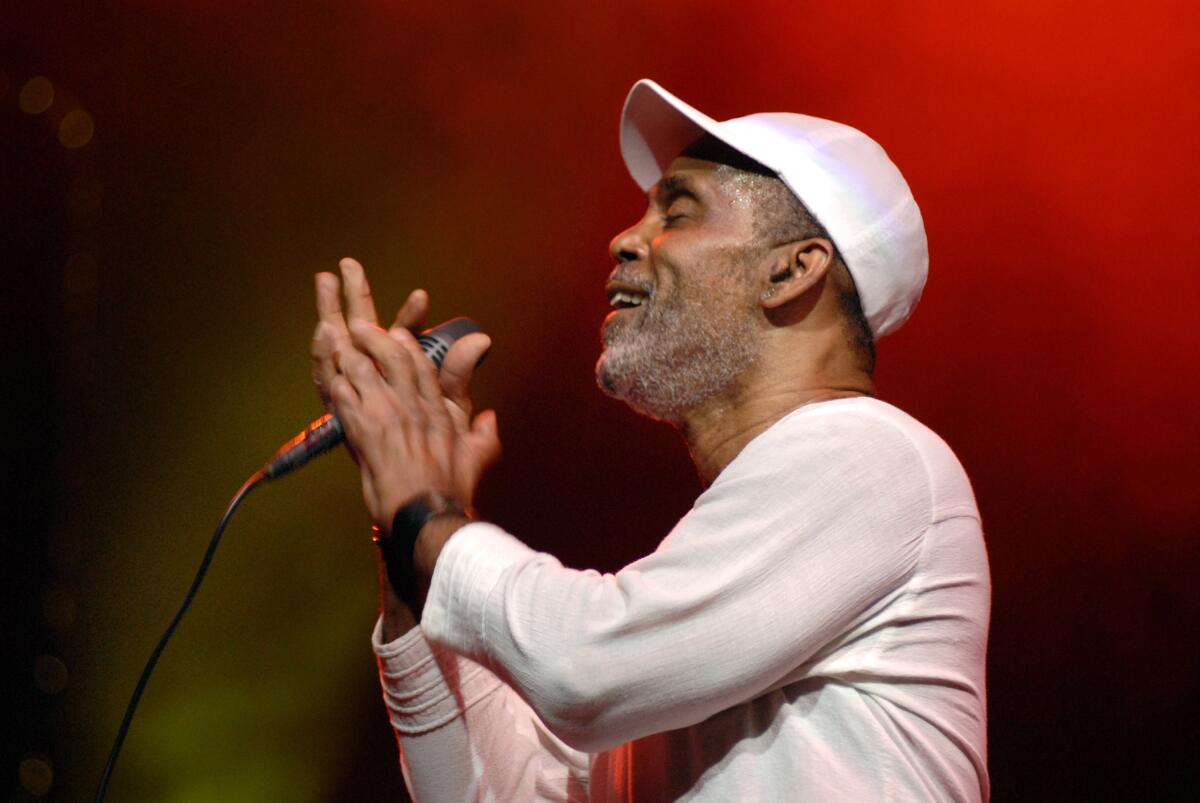

Frankie Beverly performs at the 2019 Essence Festival at the Mercedes-Benz Superdome on Sunday, July 7, 2019, in New Orleans.

(Donald Traill/Associated Press)

Again and again you can be sure

There will be pain, but you will persevere.

Where there is a flower there is sun and rain.

Oh, but it's wonderful, they are both one and the same.

At one point during the recording, Beverly recalls a story where someone asked her why she had chosen New Orleans to record a live album. Her answer was perfect in its simplicity: “Well, why not?” Through the lens of time, we can now see that Beverly’s choice of that city was the perfect setting.

Following slavery came the New Orleans Massacre of 1866, the race riots of 1900, and other terrorist attacks that left countless people dead and destroyed black businesses and homes. When Saenger's construction began in 1924, there was prosperity in New Orleans, but Jim Crow laws kept blacks disenfranchised.

And then, just two months after the theater opened, the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 devastated the region, causing more than $1 billion in damage, equivalent to one-third of the federal budget at the time.

The flood killed more than 1,000 people and displaced another 700,000. Many of the victims were descendants of slaves who had been forced to work as sharecroppers. A mile from Saenger is the restaurant where civil rights figures such as Thurgood Marshall and Martin Luther King Jr. prayed and ate while meeting with local leaders to strategize about how to dismantle oppressive laws.

This rich, storied history, each of its turning points, contributed to the formation of the New Orleans community and is reflected in the voice of the audience heard on that 1980 recording. The hits were established before Saenger. What made the album transformative was the confirmation of a shared experience and a shared resilience, expressed by those who attended.

The summer “Before I Let Go” first hit the airwaves, the death of Ernest R. Lacy would spark months of protests on the streets of Milwaukee.

Lacy, a 22-year-old black man, was helping his cousin paint his apartment when he decided to walk to a convenience store to get something to eat. Police confronted him, claiming he fit the description of a rape suspect. Lacy died while in their custody. The woman who had been raped later identified her attacker, and he was convicted. Lacy was innocent.

In times when it was easier to give in to hatred and despair, Beverly championed love and resolution with a set of timeless classics that can be heard at any barbecue worth fighting the 405 traffic to get to. A soothing balm filled with wisdom and warmth, Maze’s concerts were part family reunion, part community therapy.

Beverly received lifetime achievement awards from both BET and the NAACP. Her career spanned several eras, her voice spawned nine gold records, and her music influenced generations.

But, to the Recording Academy's shame, she never received a Grammy. The Grammys could yet correct that oversight and honor Beverly as she deserves. Because it wasn't talent that limited Beverly's reach, it was the industry.

Black people had created the blues long before Mamie Smith entered the studio in 1920 to record what is considered the first blues record. The success of Smith's recording gave rise to “race records,” leading to Billboard listing “Harlem's Hottest Records” in the 1940s.

For decades, Motown was ignored during awards season. By 1985, the American Music Awards had included a “Favorite Black Single” category as a way to keep everyone happy. It was decades upon decades of trying to contain something as organic as music, like forcing an amoeba to hold a form.

R&B legend Frankie Beverly is stepping down as lead singer of 'Maze' following a farewell tour that kicks off in March.

(Frank Mullen/Associated Press)

It remains a struggle for the industry, so much so that the nation was captivated earlier this year. When Tracy Chapman took the stage Together, with Luke Combs and with the help of a story about poverty in America, they reminded us all that music was never meant to tear us apart.

It's there to keep us together.

Beverly understood this as well as anyone.

@LZGranderson