“Macbeth” is riddled with casualties, and not just on the fictional battlefield. The tragedy has destroyed a battalion of the best directors and actors, who have been victims of the true curse of the work: its deceptive dramatic difficulty.

The problem is contradictory. Why does a play as fascinatingly theatrical as “Macbeth” arouse the audience's interest only to exhaust it at the end?

Macbeth's path as a protagonist is strange. At the beginning of the play, he is a war hero with notorious scruples. But after killing the king to secure the throne, he becomes a rampant tyrant, descending into paranoia and carnage.

The theatrical appeal of the supernatural dimension is irresistible. As a young reader of Shakespeare, I was captivated by the dizzying language, the diabolical atmosphere, and the horrible plight of a character who achieves his unconscious desire at the cost of his soul.

I consider “Macbeth” to be Shakespeare's most psychological tragedy, but in a completely different way than “Hamlet,” which focuses on the most introspective character in all of literature. Macbeth, a man of battle, is not particularly selfish. His soliloquies come early and explore his plans of action rather than the root of his feelings.

The psychology in “Macbeth” is externalized. The outer world reflects the inner reality. Even what is hidden in the play is linked to Macbeth's thoughts. The strange sisters who greet him with prophecies of his future greatness do not instruct him on what he must do to attain the throne. They awaken temptation, but ambition is already rotting inside.

The test for the actor playing Macbeth is handling those moments when the audience gets a fleeting glimpse of the character's moral and emotional struggles. In the theater, it's easy to lose sight of Macbeth's misgivings and regrets amid the thrilling witchcraft and suspenseful criminality.

“Macbeth” requires agility of concentration. One of the reasons the play may have a higher success rate on screen than on stage is that film has the advantage of being able to move effortlessly between special effects and close-ups.

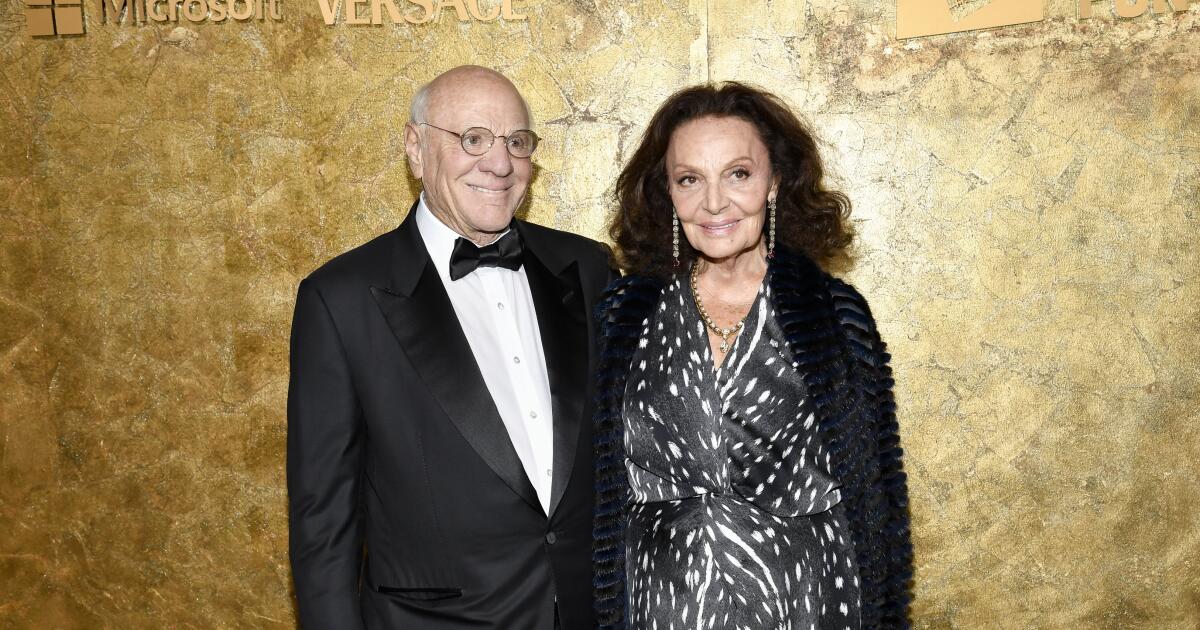

The latest film version, starring Ralph Fiennes and Indira Varma, combines the best of both worlds. It began as a stage production that was filmed in London and screened in select cinemas on Thursdays and Sundays. Fiennes (a distinguished classical theater actor who directed and starred in a film version of Shakespeare's most stark tragedy, “Coriolanus”) and Varma (who played Ellaria Sand on HBO's “Game of Thrones”) meet in the final week of his career at the Shakespeare Theater Company's sold-out American theatrical performance in Washington, DC

Directed by STC artistic director Simon Godwin, this modern-dressed “Macbeth” is based on an adaptation by Emily Burns that sticks largely to Shakespeare’s text. Having watched the film on my laptop, I can't say I had the ideal viewing experience to appreciate the full effect of the staging.

I found the murder scenes more heartbreaking than the artificial spectacle of war. Witches in street clothes suggest a gang of troublesome girls. The way Godwin employs these women as a chorus, watching scenes in which they do not participate, gives their watchful presence more meaning than I could decode. What is clear, however, is that the Macbeths are lost in their pact with evil.

Fiennes' Macbeth is an old warrior, battle-hardened but weary in spirit. Banquo (Steffan Rhodri), his faithful friend in the countryside, looks even older. Covered in blood after a hard-fought victory, both look ready to retire, perhaps somewhere milder on the Scottish coast, preferably not too noisy after all the clamor of their campaigns.

One of the first clues that Macbeth has long dreamed of being king is his reaction to the witches' news that he “will be king in the future.” “Good sir, why does he start and seem afraid? / Things that do sound so fair,” Banquo questions him in my edition of the work.

This note in the text is one of those small opportunities Shakespeare provides to clarify that Macbeth is not simply a puppet of fate. Fiennes doesn't emphasize the moment, but he makes the most of an early comment in which he is already contemplating removing the king's eldest son, Malcolm, the heir apparent, from his path to the monarchy.

Lady Macbeth has not yet sunk her claws into her husband. Harold Bloom reveled in the dark irony that the Macbeths have the best marriage in all of Shakespeare. He probably wouldn't draw that conclusion if he were alive to see this production.

Varma's Lady Macbeth is clearly the dominant force in this house. Her tone is scolding, full of maternal frustration. Her husband's hesitant nature infuriates her. When Macbeth's scruples about committing regicide get the best of him, she rebukes him mercilessly. “Give birth only to sons,” he tells her, kneeling before her and placing the side of her head on her womb, almost as if he wants to return to that maternal security.

Slow of speech, Fiennes' Macbeth gives us a hint of what Hamlet would be like if he had survived and learned to play the deadly game of power politics. Sigmund Freud would no doubt have attributed Macbeth's problems to his unresolved Oedipus complex. Lurking beneath this military machine is a vulnerable boy who doesn't want to cross his mother.

Even before Macbeth sees Banquo's ghost at the banquet, he adopts a version of Hamlet's mischievous disposition, laughing strangely and behaving erratically. Lady Macbeth looks about to slap him. When the freshly murdered Banquo bursts into the party, Macbeth's breakdown accelerates, suggesting a psychotic break more than a bad conscience.

A Hamletian version of Macbeth is inherently problematic. While Hamlet is characterized by deliberation and delay, Macbeth moves through the world like a runaway freight train. The character takes pride in the way his violent temper overcomes his reason. How else could he have become a decorated general?

The truth is that if Macbeth had even a fraction of Hamlet's philosophical mindset, he would never have killed the king. But Fiennes' approach has a positive side. My sympathy for the character grew, something unusual in my experience with productions of this play. Even when Fiennes' Macbeth orders the death of the Macduffs, as matter-of-factly as if he were telling the cook what to make for dinner that night, he reveals a character tragically lost to himself.

Both Lady Macduff (Rebecca Scroggs) and Macduff (Ben Turner) are devastatingly moving in their actor-proof roles. Shakespeare, an astute architect of the audience's experience, releases a torrent of emotion in his various scenes.

In the castle, on the contrary, that natural feeling is repressed. When Lady Macbeth sleepwalks to her guilty death, the most moving aspect is the abrupt way in which her husband gets on with her business.

The paths of the Macbeths diverge with ironic antitheses. Lady Macbeth proves that she is not a fourth witch immune to guilt, but a mortal woman unable to keep her sins buried.

Macbeth, on the other hand, has lost the ability to feel anything. Fiennes allows us to register the enormity of this loss. In my experience, it is easier to identify with and excuse the ambition of a younger Macbeth. But Fiennes and Denzel Washington in Joel Coen's 2021 film “The Tragedy of Macbeth” paint vivid portraits of childless men, haunted by death, with nothing left to live for except the empty pursuit of power.

'Macbeth'

Not qualified

Execution time: 2 hours, 30 minutes

Playing: In limited release, Thursday, May 2 at 7 pm; 1:00 p.m. on Sunday, May 5; 1 pm Monday, May 6 (Laemmle Film Center, Santa Monica only)

Information: MacbethinCinemas.com