For decades, Charles Burnett's film was little more than a rumor. Filmed during the weekends at the beginning of the 1970s with a cast mostly non -professional and a budget that did not reach five figures, “Killer of Sheep” would not receive its first public projection until the fall of 1978 at the Whitney Museum in New York. Sporadically playing only in festivals, universities and museums, the film failed to obtain an adequate theatrical release until 2007, its complicated musical authorizations will apparently condemn him to darkness. Before that, many of us had never seen “murderer of sheep”, but, in fact, we had not yet seen it completely.

Now reaching the theaters in a beautiful 4K restoration, “Killer of Sheep” is finally complete, with the Dinah Washington version of “informable”, which could not be authorized for the launch of 2007, returned to the moving final stretches of the film. Due to its imposing reputation, praised as one of the best films in our city, a distinctive seal of US Neorealism and the pinnacle of the black independent filmmaker movement called the Los Angeles rebellion, the film can confuse the first -time spectators who assume that all the masterpieces should be Swgaggering, Visionary Totems. It is not so. Some can be gentle and tender, tuned with the rhythms of everyday life. According to the program, he points out that he accompanied the film's premiere of the film, Burnett sought to “try to recreate a situation without reducing life to a simple plot.” Many small things happen in “sheep murderer”, nothing of great consequence. But the expansion of life itself is deep.

Burnett was a student graduated from UCLA at age 20 when he created his story of Stan (Henry GG Sanders), a husband who lives in Watts and father of two children who is employed in a slaughterhouse. His gloomy work that manages the Dead sheep gives the movie his title, but in reality little time is spent in Stan's work. These juxtaposed cattle scenes for cattle and skin bodies still leave an impression, but they are just a thread in a wire tapestry, none of them gave more importance than others.

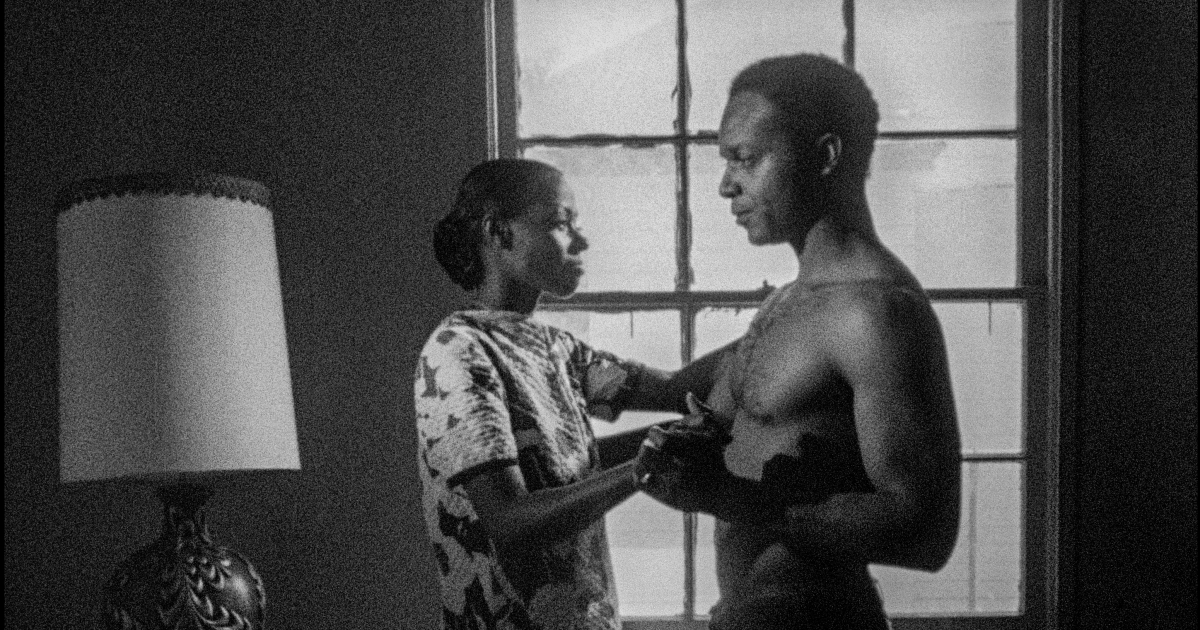

Instead of a conventional narrative, “murderer of sheep” presents us with a mood. Stan's face is one of the perpetual exhaustion, matched by his name without a name (Kaycee Moore), which projects a silent sadness. In fragments, we have an idea of a family and the impoverished community around it. There is a scene in which Stan's friends recruit him without success for an illicit scheme. In another, Stan and a different friend try to move a heavy car engine to the rear of a truck, with comicly pathetic results. In another place, the owner of a white store flirts with Stan, suggesting that he should work for her.

Each scene is a separate small episode, but everyone connects again to the pain and resistance that defines the existence of Stan. At first, Stan complains about his problems to his friend Oscar, who replies: “Why don't you kill yourself? You will be much happier.” Stan resists that notion, although while he looks at his little daughter with a silly rubber dog mask, he admits: “However, I have the feeling that I could do some damage to someone else.” The tone is more tired of the bones than threatening, and transports to the entire “sheep murderer”, which does not contain tragedies or important turns, only a wireless elimination such as its 16 mm black and white images, filmed by Burnett himself, chronally people of the working class.

The misleadingly modest approach of the film denies a radical strategy to represent ordinary black life at a time when such images were barely in abundance. The shots of children who throw rocks aimlessly to the load trains that are passing are Plainspoken, presented with documentary simplicity. And the dialogue is largely functional, Burnett never builds a great thesis, refusing to reduce the watts to clichés from the city center or its inhabitants to the saints with a deer eyes.

In the place of stereotypes, “Killer of Sheep” offers a discreet anthem to the great migration and the black families that went from the south to Los Angeles, looking for a new beginning but finding an inhospitable landing place. With blues, R&B and jazz in the soundtrack (music often expresses the pain and joy that the characters are bottled), the film is a wonder of accidental beauty, the occasional impressive sequence manufactured with a minimum of fuss.

Sanders, who had appeared in some films before “Killer of Sheep”, skillfully plays a man whose depression extends beyond the lack of money. To drift and emascular, Stan is less a patriarch than the captain defeated from a ship that sinks, drowning in his uselessness. But the performance does not allow space for the pity, an even more true feat of its Moore co -star, a crucial figure in the future films of Los Angeles's rebellion such as “blessing their small hearts” and “dust daughters.” Moore, who died in 2021, could say everything with a look, and as Stan's wife, communicates both the disappointment and resistant love that this woman feels for her husband. When a second is taken to examine in the reflection of a marijuana lid, illuminates so many not appreciated mothers. And when Stan and his wife feel silent in their living room, they scored “This Bitter Earth” by Dinah Washington, his brief devasta respite. “Today you are young,” Licks Washington. “Too soon, you are old.”

Burnett selected the songs of his film carefully, selecting a counterpoint with the moving to his critical portrait of inequality, not only in Los Angeles but in the country as a whole. The political activist and singer Paul Robeson, who died a year before “Killer of Sheep” was completed, is throughout the soundtrack, his booming voice serves as a moral compass, never again than in “The house where I live”, which looms on a scene of black children playing in a watt full of dirty streets and abandoned buildings. “What is America for me?” Robeson wonders. “A name? A map? Or the flag I see?” The film asks the same question and Robeson provides the answer: “All races, all religions / That is America for me.” “Killer of Sheep” shows us a part of that America, the invisible became visible, from the sea to the brilliant sea.

'Ovejas murderer'

Not qualified

Execution time: 1 hour, 20 minutes

Playing: Open on Friday, April 25 at the EMMMLE NOHO 7