The new documentary “Power,” which traces the history of policing in America, is based on questions: Who exactly should police serve? And what interests do they protect? Using an essay format, the film draws on an impressive roster of legal experts, academics, journalists, and law enforcement officials to take the viewer on a probing investigation of a topic that gets to the heart of social divisions.

When director Yance Ford's 2017 film “Strong Island” was nominated for an Oscar for documentary feature, it made him the first openly transgender director to have a film nominated for an Academy Award.

“Strong Island” examines the story of how Ford's brother, William, then a 24-year-old teacher, was shot and killed by a 19-year-old white mechanic in 1992 in an incident that a grand jury found justifiable. The film explores in great detail the impact the criminal justice system has on a family's grief.

With “Power,” Ford takes on a much broader scope, while still grounding the documentary heavily in personal inquiry and curiosity. Police's primary missions of protecting property and controlling populations are often at odds with public safety and community concerns. While the film doesn't offer easy answers, it does point out what could be done to make relations between police and citizens less adversarial.

“This film is a tool for the people who do this work,” Ford, 52, said during a recent interview. “I was hoping it would be something that people who work could use to reimagine our definition of public safety.”

“Power,” which premiered earlier this year at the Sundance Film Festival, is in theaters Friday and begins streaming on Netflix on May 17. While traveling to promote the film, Ford recently spoke to The Times over Zoom from Toronto.

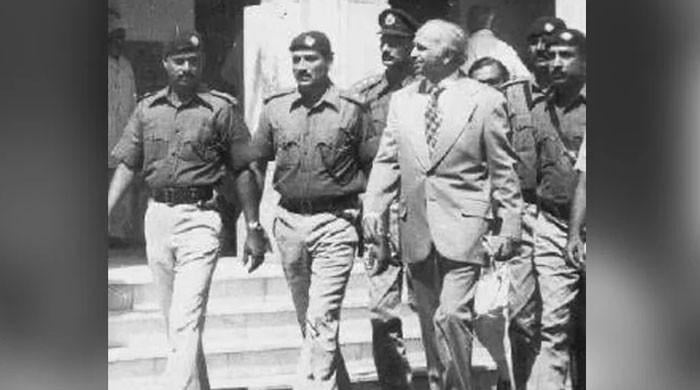

A scene from the documentary “Power”.

(Netflix)

Before we get into the movie, as you've been watching the footage of police officers on college campuses across the country being called in to clear the camps of student protesters: what do you think of that?

It's very difficult to put into words what I think about it, because when I see these images, I remember how little we learn from history. This reminds me how easy it is for people to regurgitate talking points that were used to delegitimize student movements in the 60s, talk about outside agitators, talk about professional agitators. This all feels so familiar to me that it honestly makes me wonder if America is simply doomed to repeat the past over and over again. Universities are calling on the police to do what the police do, which is contain, control and expel people who are considered disruptors of the status quo.

“Strong Island” was a very personal film, exploring his family's experience. with the criminal justice system. Did “Force” get out of a try to get a 10,000 foot view of what had happened?

In many ways, I've been thinking about policing since there were detectives at my parents' house explaining to them why the person who killed my brother wasn't going to be charged with a crime. But when George Floyd was murdered and protests ensued afterward, I saw and felt something different in the police reaction to protests across the country. And in the city where I live, New York, that felt different. It felt dangerous. He felt unrestrained. And I felt like there had been a change. This feeling made me ask: “Is this what the police are for?” in a way that seemed different to me than the times I had asked that question in the past. These were police officers acting like an occupying force and, frankly, like the armies they have become.

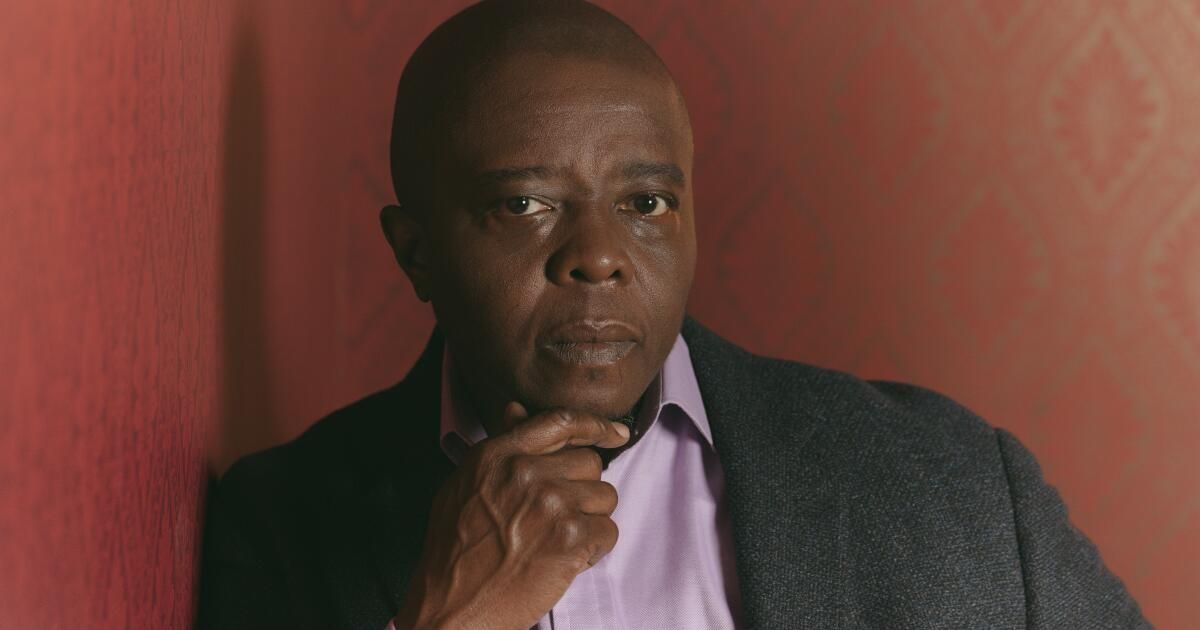

Director Yance Ford, photographed in New York City in May.

(Justin Jun Lee / For The Times)

And that was what started the line of questioning that led to the film. It was less about the 10,000-foot view of what my family had been through and more about what I was seeing on the streets of the United States and around the world. Being in New York watching protesters being beaten [a crowd-control confinement tactic], pepper-sprayed: aggression isn't even the word. It was the kind of violent response that reacted as if protesters were the problem, rather than Derek Chauvin's murder of George Floyd being the problem. So when I saw this violent response to the protests, I began to wonder about the purpose, meaning, and function of police in a different way.

The film begins with a statement from you. in which you say, “This movie requires curiosity, or at least suspicion.” Can you expand on this?

I put it at the top of the movie because I know this issue of policing is one where the current debate has been Black Lives Matter. [or] Blue lives matter. Whenever the police question is raised as an “issue,” there are people who will think that a documentary will be a polemic against the police or that it will be something that reinforces their own analysis of the police. And what I wanted to do was invite the audience, regardless of where they feel in relation to this issue, to see the film as they are. So I know that if you have a particular point of view, you will be suspicious of me and my intentions. And then I wanted to say: You know what? I understand. I don't assume you'll trust me if you're suspicious. I want you to see the movie anyway. I understand that you may be curious to know the information about this movie because you are predisposed to be interested, and that predisposition is fine too. I recognize all that and I would like you to be in the film anyway.

An image from the documentary “Power” by Yance Ford.

(Netflix)

ohnortheast of things including that made me feel I had a lot to learn It is the simple fact that the first municipal police did not even begins until the 1880s. tThat sounds so recent. I know it for myself And I think probably a lot of viewers assume that police existed long before that.

I think that's the best thing about this movie. It is proven on one side and on the other. Because I assume and hope that when we release the movie, there will be people who say, “That's not right.” And luckily, my partners at Multitude Films and the entire team, as well as our fantastic fact-checker, will be able to say, “Actually, no, we have our receipts here. “We have done the investigation.” And policing is not as old as you think. It is an invention from the mid-19th century and was not invented to ensure or maintain public safety or to combat crime.

It was invented to protect property and control property and control movement and break unions and help the country expand westward by removing indigenous people from their lands. There are many ways people can discuss policing and where it might go from here. But one of the really important things for us was to establish facts and investigate them in such a way that you couldn't argue with them. By doing that, we help people get out of the moment and start thinking about the ways that history impacts the present.

One of the most surprising characters in the film is Charlie Adams, the Minneapolis police officer. working to reform policing from within the institution itself. Seeing someone so close to where George Floyd lived and died, and feeling like policing doesn't have to exist as we know it, how did you come to find Charlie Adams?

We researched many different police officers, police commanders, and police chiefs from around the country who worked in their departments. And Charlie Adams moved up to a spot on the list that was interesting to us because he's in Minneapolis and he's been working for a long time trying to help his officers in District 4 understand the perspective of the community and the people who live in the community in which they serve. Charlie Adams is a great character because he is someone who is seen to have good intentions, but he is also someone who is restricted by the contours of the institution in which he works. There are aspects of the criminal legal system that limit the effectiveness of what he can do. I think Charlie Adams tries to do what he can, but when you see this where it clashes with the reality of policing, it helps you understand that it has to be about more than just individual bosses or officers.

When we think about what keeps communities safe, we cannot fall into the trap of talking about the behavior of individuals or attempting another round of reforms arising from community policing. We really have to approach it in a different way and with solutions that come from communities to the police, and think about institutional reform or reimagining a different institution. I think one of the things that being with Inspector Adams really shows is that there is a really powerful institution behind each individual officer. And it is the institution that needs to be addressed.

There's a moment in the film where you tell an interviewee that you want to address this idea of he “us of everything.” Is that one of the challenges when talking about policing? It is Is it difficult to address the issues and concerns of all these separate communities, different people, different sets of “we”?

“Who is the 'we,'” in my opinion, relates directly to the question at the end of the film about the power that grants nothing without a demand. Because knowing who “we” are is part of defining what the demand will be. What demand are you going to make of the police? What demand am I going to make of the police? As soon as we get specific about who we are, we can dig deeper and understand what we will demand from surveillance. Because for too long the people whose job it is to regulate the police, to tell the police what their job is and how to do their job, have walked away from that or let the police be this self-regulator. industry.

If it were a business, we'd say, “Internet companies, you can regulate yourselves.” And we know from history how well self-regulation has gone in the business world. But we haven't had people in elected office who have been willing to take on their responsibility to regulate the police. And so people are deciding that it is their job as citizens to do so.

Why did you decide to call the movie “Power” instead of just calling it “Police”?

Because they are synonyms, they are the same. The police are the power of the State made reality. You and I and others, some more than you and I, will interact with police much more often than with your elected representative or senator. So in terms of how the government and the state manifest themselves in people's lives, the answer is the police. When you think about who is the most powerful person, like [journalist] Wes Lowery says that in this country, on a day-to-day basis, most people are police officers. That's why he wanted to make very clear the lens through which the film will look at police and policing.

And it's a great title too, if I do say so myself. He tells you what you are going to see. When you buy a ticket to a movie called “Power,” you get an idea of what to expect.