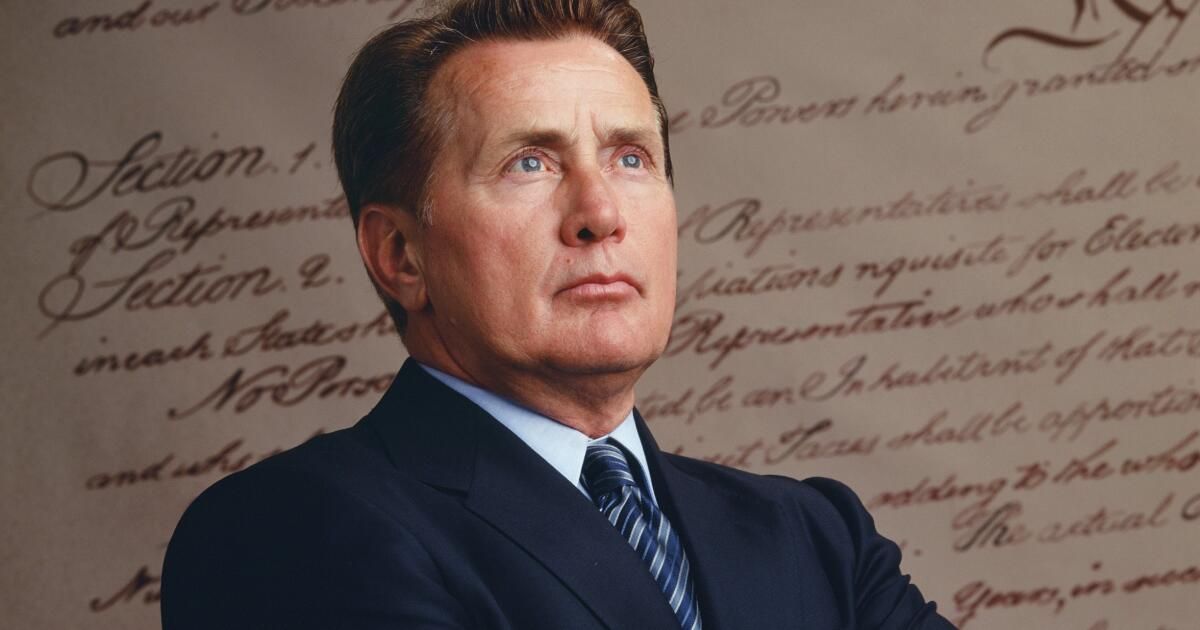

As another terribly consequential presidential election approaches, it’s hard not to fantasize about how things could be different. Imagine, for example, having a president who put his deepest values ahead of pressure from his biggest donors. Imagine someone who could truly listen and learn when faced with issues he didn’t understand rather than espousing whatever position was most politically expedient at the moment. Imagine, even, a president who inspired us, who made us feel a surge of patriotism, however skeptical we may be of that concept. In short, imagine Josiah Edward “Jed” Bartlet, president of the United States, as imagined by Aaron Sorkin and brought to life by Martin Sheen over seven seasons of NBC’s critically acclaimed and award-winning series “The West Wing.”

Two of the show’s cast members, Melissa Fitzgerald (who played Carol Fitzpatrick, assistant White House press secretary) and Mary McCormack (who played Kate Harper, deputy national security adviser), no doubt still believe in the show’s sticking power, as well as its overall positive approach to politics. They’ve written a book about the show that’s clearly aimed at current fans of the show: “What’s Next: A Backstage Pass to the West Wing, Its Cast and Crew, and Its Enduring Legacy of Service.”

Look, it’s true: I occasionally make hot chocolate in my “Bartlet for America” mug and sip it wistfully, imagining a world in which we had a President Bartlet instead of a second President Bush, perhaps followed by a President Santos, the character played by Jimmy Smits, who had radical and truly inspired plans for education reform. It’s a beautiful dream — a White House that’s more “West Wing” and less “Veep,” functional and nearly scandal-free, earnestly dedicated to improving the lives of ordinary Americans through the slow but essential work of policy change.

Yes, I know this is extremely naive; yes, I am aware that Bartlet was problematic in many ways, as was his staff; and yes, I know that “The West Wing” was, in many ways, a liberal fever dream that appropriated American exceptionalism and the ideals of patriotism. But that’s all it is: the show was a fantasy, one that hinted at an idea of how things could be, but made no attempt to assert that this was actually how things were. Sorkin himself insisted “First and foremost, if not only, this is entertainment. 'The West Wing' is not meant to be good for you… Our responsibility is to captivate you for as long as we have your attention.”

And entertain us it did, over the course of more than 150 episodes, some more memorable than others, but all including at least one gripping monologue that made this viewer, at least, believe in the possibility of a government that actually works, or that actually try work, or so it really is wants It helped that I watched bits and pieces of the show as a teenager, long before I moved to the States, when my trips to California were strictly family visits where my grandparents and aunts doted on me and spoiled me with all the frozen yogurt I wanted, unlimited TV time during which I enjoyed more channels than I knew what to do with and fascinating commercials for toys I would never own, and, best of all, bookstores so big I could get lost in them. It seemed like a more innocent time.

But of course, that wasn't the case. “The West Wing” was on when George W. Bush was taking office after a close and contested election. It was on TV when 9/11 happened, when the Patriot Act was signed, and when the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq began. The show offered an upbeat alternative, appealing especially to a certain income group; its majority of viewers, According to a 2001 study, earned more than $70,000 a year, or, in today's money, more than $120,000. Largely protected from Systemic injustices that contribute to and are caused by povertyWealthy people experienced less of our government's shortcomings and probably found the program's vision more plausible than it actually was.

As a (rather embarrassed) devotee of the show, I bought into it, too, especially the first two times I watched it from start to finish, as a teenager and early twenties. It managed to make the American political process (which I found deeply baffling, having never learned how it worked in school) exciting. Part of it, I'm sure, was the speed of the witty dialogue, for which Sorkin is famous, as well as the way the show was filmed, its long walking-and-talking scenes lending a sense of urgency to otherwise dry policy issues. The humor was also serviceable and at times educational. I'll never forget the Big Block of Cheese Day Episode during which Deputy Director of Communications Sam Seaborn is required meet a ufologist — and press secretary CJ Cregg and deputy chief of staff Josh Lyman learn (along with the rest of us) that the maps we all grew up with are Both imperialist and, frankly, misguided..

But so funny and inspiring (often at the same time, as in the brilliant two-part film) “20 hours in America”) As great as the show may be, it has glaring problems. When I rewatched it recently, I was deeply disturbed, for example, by the dynamic between Lyman and his assistant, Donna Moss. What was framed as a cute “will they/won’t they” relationship between boss and devoted employee now struck me as not only wildly unprofessional but even downright abusive, with Donna bearing the brunt of Josh’s tantrums and enduring his constant belittling of her. But it’s more than the interpersonal dynamics; the show’s occasionally over-the-top optimism and sincere belief in the United States as the greatest nation on Earth — not to mention its very white cast and casual but constant sexism — have made it, anecdotally speaking, cringeworthy to many leftists of my generation.

Old criticisms about the program’s idealism remain valid. Cynicism and frustration with the government’s slow pace have probably always existed across the spectrum of left and right. Now, with social media adding second-by-second commentary to an already fast-paced 24-hour news cycle, these feelings feel much stronger and more visible.

The writers of “What’s Next” don’t dwell on the ways the show has aged poorly. Instead, they’re relentless in pointing out its positive aspects — and, to be fair, when it originally aired, there were no other television shows that depicted the functions of government, so the politics “The West Wing” explored were likely eye-opening for many of its viewers. One episode from the first season, for example, includes a compelling argument for financial reparations for the descendants of enslaved black people, a concept as old as abolition but one that many of the show’s viewers may never have encountered before.

This particular example, however, is not mentioned in the book, which focuses on the broad idea of service and praises the show’s cast members for their social and political activism. Many have worked to support veterans and treatment courts, which emphasize rehabilitation for people with substance use disorders. “What’s Next” is an uplifting text, a fun, lighthearted read that doesn’t delve into any shameful aspects or hardships on the set.

But “The West Wing,” like almost any piece of media that endures, would only suffer from the insistence that it is perfect. The show is a messy, highly entertaining (and occasionally educational) piece of television, filled with extremely talented actors giving incredible performances, but it is not a road map to reality, nor should it be.

After President Biden's debate debacle this summer, show creator Sorkin wrote a strange opinion piece Sorkin suggested that Democrats nominate Mitt Romney, a moderate Republican, for president — a strategy to capture enough conservative voters to prevent former President Trump from regaining power. But when Biden dropped out of the race, Sorkin quickly walked back the suggestion. His op-ed was, depending on who you asked, either a frustrating or entertaining thought experiment, but it should never have been seen as actual advice for the real world. Like “The West Wing,” it was a break from reality.

Ilana Masad is a book and culture critic and author of “All My Mother’s Lovers.”