France moved the Olympic opening ceremony out of the traditional Olympic venue and onto the River Seine (and into the rain) on Friday, in what was arguably a bold, unprecedented and, given the security nightmare, a folly. An Olympics whose motto is “Open Games” ironically came with fences, checkpoints and police and soldiers numbering in the tens of thousands. But they remained virtually invisible during the broadcast, once again on NBC and also streaming on Peacock.

Almost nothing was revealed about the programme in advance, beyond a few facts and figures: 300,000 spectators were expected, a 6-kilometre route downriver from the Pont d’Austerlitz to the Eiffel Tower and the Trocadero, some 90 boats carrying 10,000 athletes, 12 thematic “scenes”. With so little to go on, it was tempting to imagine what those scenes might encompass. Bearded existentialists sipping apricot cocktails? A nude man descending a staircase? Jean-Pierre Léaud making a final appearance as Antoine Doinel? Striking railway workers? The Telephone band reunited? I had hoped to see at least one performer dressed as Jacques Tati’s M. Hulot, though I would have bet on 100. Would there be mimes?

The answer to all those questions was no. Working with a team that included a historian, a novelist, a screenwriter and a playwright, not to mention choreographers and costume designers, director Thomas Jolly — known for his marathon, 24-hour stagings of Shakespeare’s three plays, “Henry VI” plus “Richard III” — cooked up something at once stranger and more appropriate: quirky, sexy, occasionally alarming — I wouldn’t have expected Marie Antoinette to be decapitated — and, I’d say, quintessentially French. Even the rain, which, having come, stayed to enjoy, had a sort of Parisian quality to it, adding drama and romance. Though, of course, that part wasn’t in the script.

Artists during the opening ceremony in Paris, which featured decapitated Marie Antoinettes.

(Bernat Armangue / Associated Press)

Bringing the Games into the city centre and holding the ceremony on the river was a smart idea from the start. No one goes to Paris to stay home unless it's to see art or eat things cooked in butter; and if you've seen the inside of one super-lit stadium, you've seen them all. The Seine placed the athletes, riding their larger or smaller bateaux mouches, within a stone's throw of Notre Dame, the Louvre, the Tuileries, the Place Concorde, the Grand Palais and the Eiffel Tower.

A few artists had been mentioned beforehand, including the French Malian superstar Aya Nakamura; the “eco-metal” band Gojira, which, with its frequent collaborator, the French-Swiss opera singer Marina Viotti, represented the Revolution; and the never-publicly-confirmed Céline Dion, who, at the end, closed the show with a powerful rendition of Edith Piaf’s “L’Hymne à l’amour,” sung from the top of the Eiffel Tower. Lady Gaga, whose presence in the city had already been noted, opened it—if you don’t count the winged accordionist on what I assume was the Austerlitz bridge—with a glamorous cabaret production of Zizi Jeanmaire’s 1960s hit “Mon truc en plumes” set on a gilded staircase leading down to the river. That translates as “my thing with the feathers,” and there were feathers, indeed: big pink fans, pink being the shade associated with that part of the color-coded show.

Jolly mixed filmed pieces with the live performance. Most provocative was a gender-bending love story told through book titles that led to a suggested threesome (the show contained a decent amount of queer content). There was dancing on the scaffolding around Notre Dame. More crucial to the narrative, such as they were, were the segments surrounding a masked and hooded torchbearer who would also be seen in person along the route (and zip-lined above it). This part included trips through the metro, the catacombs (this was undoubtedly the first and surely the last opening ceremony to feature human skulls) and sewers inhabited by alligators, as well as the Louis Vuitton workshop (where they made the trunks that held the torch on its travels) and the Louvre, where figures left their paintings, later to emerge as giant heads in the river.

Behind the clock at the Musée d’Orsay, we saw a clip from the Lumière brothers’ seminal film about a train arriving at a station and a puppet animation referencing Georges Méliès’s “A Trip to the Moon,” “The Little Prince,” and “Planet of the Apes,” which of course included the statue the French made for us. I found this part particularly charming.

This operatic mix of media, spread across the city, could only make complete sense as television: anyone present would have seen only what was in front of them. And yet, as television, it largely failed: it further fragmented a fragmented event, alternating between parade and spectacle for about four hours, with commentary and cutaways and, after the first hour, commercials. It only spoke to the banality of television and to remind us that this is not a world without commercials. (The insertion of a clip from NBC parent company Universal's “Despicable Me” was all over the place as corporate cross-promotion.)

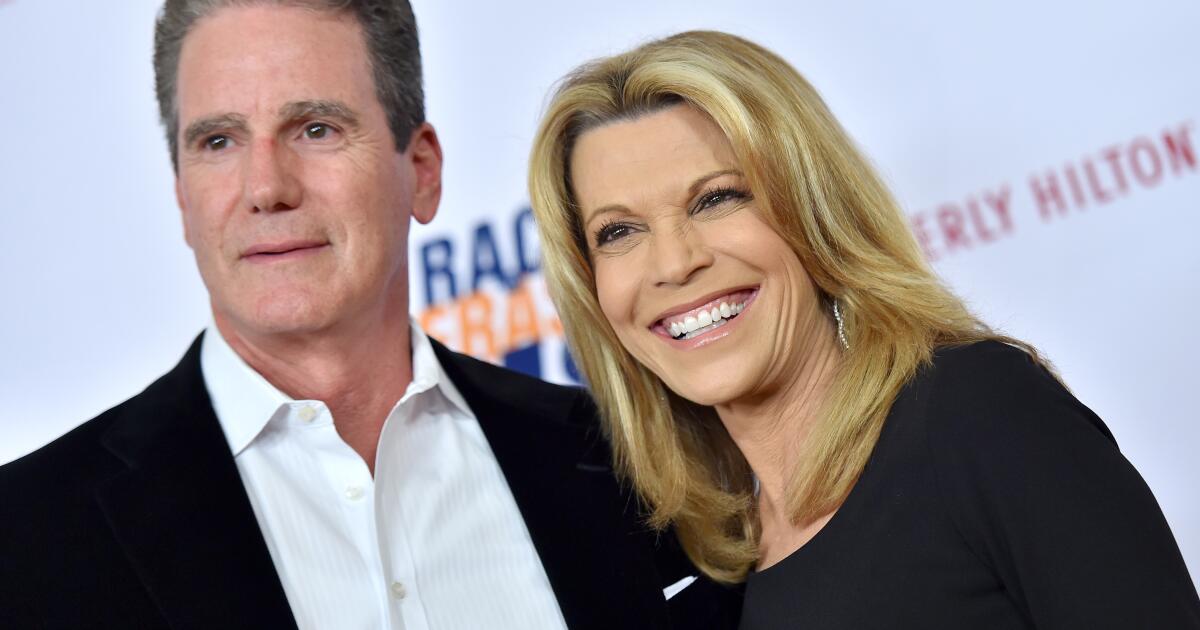

Canadian singer Celine Dion closed the opening ceremony with a performance at the Eiffel Tower.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

The comments by Mike Tirico, Kelly Clarkson and Peyton Manning had the effect of people talking during a play, or that disconcerting feeling you get when you're in a foreign country and suddenly hear American voices. Perhaps they were working at a disadvantage, given the secrecy that had surrounded the production and a less-than-native knowledge of French culture and history. But, aside from the kind of sports statistics that no spectator holds in his or her head longer than it takes to say them, they spoke largely about how they felt and how they imagined the athletes would feel. They turned the parade of athletes into the Macy's parade.

I say “mostly” they failed. Often enough, the grandeur, audacity and madness of the event shone through the screen: the mezzo-soprano Axelle Saint-Cirel singing “La Marseillaise” from atop the Grand Palais, a silver knight on a robot horse gliding along the river to carry the Olympic flag to the Trocadéro, where the athletes eventually disembarked, and where speeches by International Olympic Committee President Thomas Bach and Games President Tony Estanguet made it feel like there might be more to the Olympic spirit than winning medals.

And then came the truly moving finale, with Dion as Liberty leading the people in the famous Delacroix painting and the Eiffel Tower giving its laser show. Athletes dressed in white for many years passed the torch and became a crowd as they ran together towards the Louvre and back to the Tuileries, where a giant gold hot-air balloon (invented by the French) was tethered. It became the Olympic cauldron and then rose into the air, where I suppose it will remain until the closing ceremony comes to tell us its story.