Last week, a bipartisan group of U.S. senators introduced the NO FAKES Act, designed to protect the voices and images of artists and citizens in the age of artificial intelligence. One of the leading groups championing the bill was the Recording Industry Association of America, better known as the RIAA.

The trade group, which represents record labels on policy issues, has been in a legal and legislative spiral as advances in AI change the way music is produced, discovered and used.

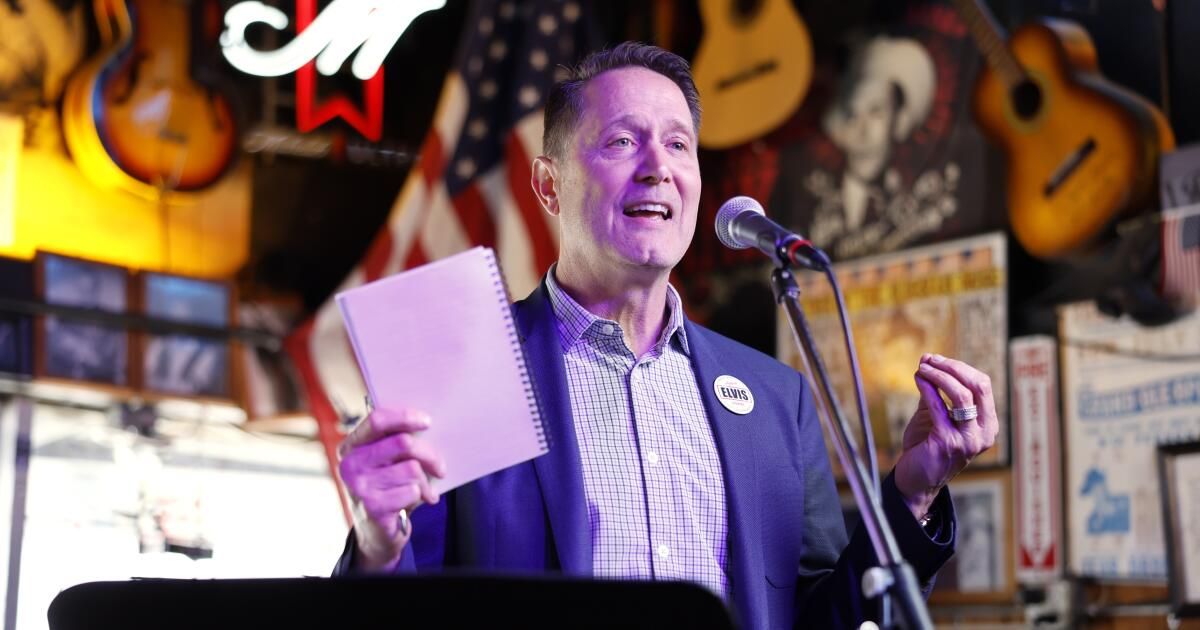

In June, the RIAA announced a lawsuit against a pair of music AI companies, Suno and Udio, alleging that they had obtained massive royalties to train their models. “Unlicensed services like Suno and Udio that claim it is ‘fair’ to copy an artist’s life’s work and exploit it for their own profit without consent or payment set back the promise of genuinely innovative AI for all of us,” RIAA head Mitch Glazier said in a statement in June.

(Suno CEO Mikey Shulman said the company “is designed to generate completely new outcomes, not memorize and regurgitate pre-existing content.)

The Times spoke to Glazier about the RIAA’s work to police and cultivate the potential of AI, the black-box conspiracies surrounding Spotify’s algorithm and how the group’s reputation as the bully of the Napster era has changed.

There's a lot of Government and legal interest in music and artificial intelligence. How would you compare this moment to the arrival of file sharing in the 1990s and streaming in the 2010s?

Add to that the threat posed by file sharing and the opportunity offered by streaming, and it's a combination of both. Like file sharing, this is a major technological shift that will have a huge impact on the music industry. AI has been used as a creative tool, but its abuse could be as big a threat as file sharing was. Companies see it as an opportunity, just as they did when streaming services could offer legal alternatives and fan-friendly platforms. But if regulators and courts don't rein in its abuse, it could be a massive threat.

Musicians already rely on artificial intelligence to correct drum loops or recommend songs. Is the threat from synthetic music and the abuse of similarities?

The real problem here is generative AI, which is non-consensual: the model is trained and no permission is asked. The market is diluted because 10 million songs can be created per day, which unfairly competes with the music of artists that were copied. Synthetic music created from generative AI as a result of training artists, and voice and visual similarity issues, where artists are basically cloned to sing something they didn't sing, are the ones that affect the most.

What were the particular dangers of the Suno and Udio models?

We suspected that they had used the music of established artists to train their model. They avoided legal consequences by changing it so that you couldn't put the name of a particular artist on it. They added new subscription services and monetized it very quickly, when we knew that they hadn't gotten consent for the input. The reason we had to get ahead of it was because the technology was moving very fast and they're not transparent about their input.

How would you know what music they were training to?

The result itself contained fragments that were recognizable. Jason Derulo tags his music singing “Jason Derulo.” When the AI result does that, you think, “I think I know where that came from.”

One of the key pieces in this case was a quote from one of the companies' investors, who basically said, “I wouldn't have invested in this company if they had respected copyright law, that would be a huge restriction.” As these services grow and begin to mature, by filing this lawsuit, it sends a signal to venture capitalists that it may not be as safe to invest their money in a service like this if you don't get consent for their input.

The RIAA has advocated for bills like the NO FAKES Act, which echoes concerns that actors could have their digital likeness compromised or transferred. Is this something musicians should also be concerned about?

Of course. This is an example where record companies and artists have worked closely together to ensure that voices and images cannot be used without consent. If someone puts words in your mouth using your own voice, what can that do to your career and reputation?

We've sent thousands of notices for platforms to take down not just songs like the fake Drake and The Weeknd ones, but countless other kinds of cloning, misinformation, and things that are funny but generally harmful. We've had mixed luck with the platforms. That's why we're pushing so hard to protect voice and image rights at the federal level, which would apply to all people. If someone wants to make a replica with your consent, that's fine. But if you don't, you can go after them and get it taken down quickly to limit the damage.

Tennessee passed the ELVIS Act dealing with this. It's interesting that Nashville has been a pioneer in this area.

I don't think it's a coincidence. A lot of country artists spoke out very quickly because their fans demand authenticity. Not that other genres don't, but I think country has a special appeal. Lainey Wilson testified in favor of the House bill and defended it with great fervor. Randy Travis testified. Nashville has been at the center of the passage of legislation and artists speaking out about it.

Politicians understand that their opponents can clone them and force them to express a political position contrary to the one they actually defend. That's how Marsha Blackburn and Chris Coons come together on this issue.

Many artists are struggling in today's music economy. I can imagine a world where record labels exert pressure to give up those rights.

There need to be boundaries. If you sign with a major label, you're not going to have a broad grant of rights forever. Let's say you're a 14-year-old kid and a manager says, “I can get you a record label contract, all you have to do is sign here and you'll be signing over the rights to your name, image and likeness forever, even after you're dead for whatever purpose.” Those are practices that need to be addressed. We worked on this legislation with SAG-AFTRA to make sure there were boundaries.

I'm not too worried about fake Drake climbing the charts, but streaming services could put a finger on the scales of the synthetic music they own. Does that worry you?

There will definitely be a transition. I wonder what's going to happen with music production companies giving their catalogues to AI companies, so they can generate more music. If you're writing commercial music and you get a cut of what the company licenses, what does that mean for you? AI music is cheap. There's no human to pay. Will platforms use their algorithms to direct people to AI-generated music, because there are no royalties? I think that's a real potential problem for human artists.

Then there's the issue of dilution. Are they going to allow these aggregators to automatically upload 10 million songs a day that have to compete for an artist to gain popularity? Which ones will the algorithms favor? If people like something, will they automatically produce more of it? Will they label it as such? I think those are important business questions.

At the end of the day, fans have to discriminate between having a connection with human artists. At the end of the day, the market is going to serve fans who want authenticity. If we can get the legal rights so artists can protect themselves, I think the fans will do the rest.

There is conspiracies on the reasons why certain songs have taken off on Spotify. Discovery Mode It’s also a point of contention. Are there new pressures on artists and labels to give up money in exchange for visibility there, or fears that Spotify has its own agenda on what becomes popular?

I don't think major label artists would do that kind of deal, but I don't think it's scalable either, because then it's pointless. If everyone gave up royalties in order to promote themselves, then it wouldn't be promotion anymore, because everyone would get them. It's counterproductive.

But the push for transparency is incredibly important. We don't want to become an industry where artists can't get data on themselves to promote themselves and record labels can't get data on artists to identify their audiences. No one is going to give away their secret formula, but the black box problem is real and it creates angst and fuels conspiracy theories. It makes people feel like there's a thumb on the scale and it's not fair.

In the 90s and 2000s, young music fans were allied with tech companies against the record labels. Now, you see more fans allied against technology. How have those alliances changed since you've been at the RIAA?

Record companies are no longer gatekeepers. They don't control their own distribution. The control is now in the hands of the technology platforms. I think we are on the same side as fans and artists today, because we have the same interests. Man has changed and now the technology platforms are man.

Throughout my life, the RIAA was synonymous with suing music fans for downloading songs on Napster. Do you still encounter that feeling in relation to your work today?

It's a lot more fun now. The industry has changed, but our mission remains the same. How do we protect ourselves from people who infringe on the content of the artists our record companies work with? And furthermore, how do we protect their name, image and likeness? The rise of streaming and the democratization of the industry has changed the perspective on enforcing those rights.

What conflicts and changes are coming in music and AI?

How much human input does there have to be in something that's partly made by a machine for it to be copyrightable? We don't want Suno to say that he owns all the music generated by his machine. On the other hand, there's Randy Travis' new song, where an AI extracted his voice so that he could create art when he can't sing anymore. Is that enough human input? I think it's a fascinating piece on the board.