On the shelf

From the Earth to the Moon

By Moon Unit Zappa

Dey Street Books: 368 pages, $30

If you purchase books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission. Librería.orgwhose rates support independent bookstores.

Moon Unit Zappa recalls the moment he became the voice of a generation.

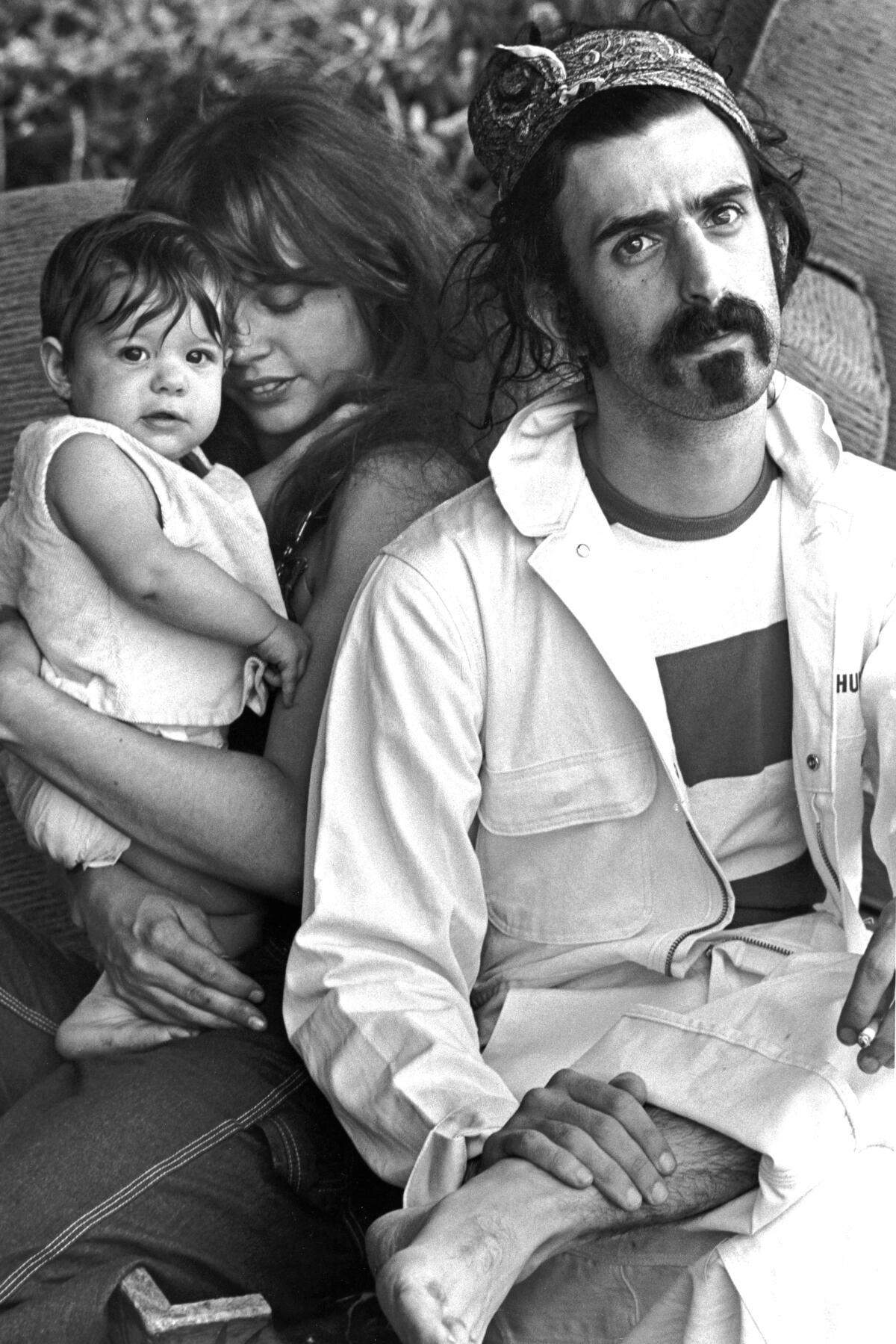

It was a school night in 1982 when musician Frank Zappa woke up his 13-year-old daughter. Frank needed her in his home studio, right away. It was the first time Moon had been summoned to her father’s sanctuary, the place where he essentially lived and worked when not on tour. As she recounts in her new memoir, “Earth to Moon,” out Tuesday, her father said the five magic words: “We’re going to record a song.”

Dazed, “with unbrushed teeth,” Moon entered the soundproof recording booth. She was offered headphones and microphones adjusted. A shiver of excitement ran through her. Frank had obviously read the letter Moon had slipped under the studio door a few days earlier, asking for the chance to “do my ‘Encino accent’ or my ‘surfer language’” on her new record; written correspondence was the only way Moon could think of to get her father’s attention.

Now everything was happening.

Ordered to “speak and improvise in that funny voice,” Moon got into character, while Frank asked her to “try working with ‘gagging myself with a spoon’ and ‘tubular.'” And it was over in an instant. A visibly pleased Frank gave Moon a hug and sent her back to bed.

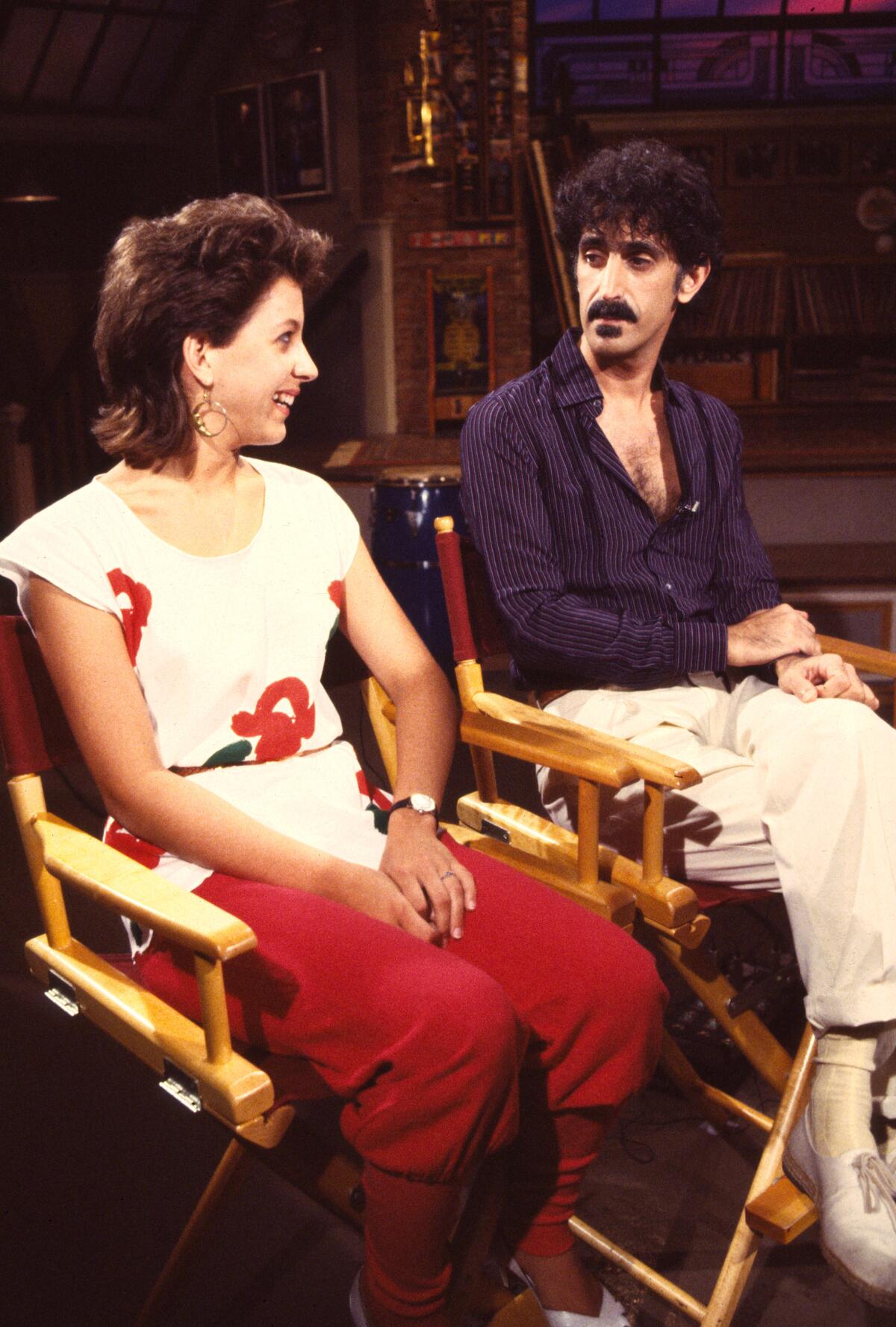

That recording became 1982’s “Valley Girl,” a massive hit. More than four decades later, Moon’s “Valleyspeak” remains inextricably linked to 1980s Southern California youth culture. So why was it the one event in her life she didn’t want to write about in her memoir? “It was a painful time,” Moon says. “It was the section I had to wait until the end to finally write.”

What should have been a triumph for Moon became a source of consternation and mixed feelings, familiar emotional territory for the son of two powerful, erratic narcissists who had little patience for parenting. The triumph of “Valley Girl,” Frank Zappa’s only Top 40 hit, was Frank’s alone.

So Moon writes that she had to “come to terms with the paradox of being told at home by my loved ones that my contribution meant nothing, while the world saw me as a smart, funny, talented person.” It took her years to unravel this, especially when she discovered that her parents had withheld her royalties from “Valley Girl.”

Tense negotiations over money, feelings, and time consumed much of Moon’s young life. His father, a brilliant musical scholar and beloved guitar hero, was a workaholic and therefore a fleeting presence. His mother, Gail, in contrast, was all too present: she was a demanding and often harassing parent. Living with his parents and three younger siblings — Ahmet, Dweezil, and Diva — in a sprawling house in Laurel Canyon that became a place of work and play for three decades, Moon struggled to find his own safe harbor away from the high-intensity chaos of his domestic life.

Frank Zappa at his home in Laurel Canyon in 1968 with his wife Gail Zappa and daughter Moon Unit.

(Michael Ochs/Getty Images Archives)

Suffice it to say, it wasn’t. The void Gail Zappa filled in the absence of her always-touring husband was more like a raging vortex. “In some ways, I never felt like it was my story to tell, and I encouraged Gail to write it down,” Zappa says. “But when he died, I had to find out who those people were.” Moon’s memoir is a self-portrait of an insecure and often confused child, who adored her absent father and thirsted for maternal affection. “What do you do when your mother is your first stalker?” she says. “When you come from that kind of emotional trauma, all you can think about is escape.”

The ever-under-construction compound, with its “oleanders… and old milk cartons… R. Crumb comics, empty tea and coffee cups and ashtrays,” was often inhabited, Moon writes, by naked strangers “frolicking or making candles.” “It was not unlike the feeling of being a kid allowed to ride in the car as it goes through a car wash,” Zappa says. He’s eating a late lunch at the Granville restaurant in North Hollywood, wearing a crystal necklace from his home in Taos, New Mexico. “Safe in the bubble, I looked in wonder at all the mechanisms of my environment. But there was too much nudity and noise!” he adds.

Gail fed her children’s developing minds notions of predestiny, aliens, and the occult. She also read them bedtime stories and shared their bed when Frank was away, but this parental kindness was usually tempered by her cruel side. According to Moon, her mother didn’t have the tools to raise a family without creating turmoil. “Gail was very dependent on my father in many ways,” Zappa says. “But he was away so often that as an adult, I strangely feel more empathy for her now. If you don’t do any work on yourself, you’re going to be miserable.”

Gail’s organizing principle was to give Frank the space to do his work; his job was to defuse domestic unrest as he saw fit. “Something I’ve often grappled with, and which became the impetus for the book, was this idea of whether genius is worth the collateral damage it can cause to a family,” Zappa says. “It’s the Pharaoh syndrome. You’re working for the top of the pyramid, and in the end, that’s going to come back to you.”

Moon Unit Zappa and Frank Zappa sit down for an interview with MTV in New York in 1982. Frank's hit song “Valley Girl” featured his then 14-year-old daughter Moon.

(Gary Gershoff/Getty Images)

No exit plan occurred to her. For Zappa, the pull of family was strong and often clashed with the drive to create a life apart from it. In her memoirs, Zappa writes of how she tried to leverage the success of “Valley Girl” with a spotty acting career that, in retrospect, kept her from higher education or pursuing a conventional “civilian” career. “I was living in an occult hallucination,” she says. “It didn’t occur to me to get out of show business.”

Gail died of lung cancer in 2015, 21 years after her husband's death. Despite decades of subterfuge and concealment from Gail about the state of the family's finances, Zappa had every expectation that the four children would receive an equal share of the inheritance and run the business as their mother had done. Instead, Gail died deeply in debt. When the dust settled, the house and most of the assets were transferred to Diva and Ahmet. An ugly legal battle ensued between the siblings and opened an emotional fissure that has yet to be repaired.

“I find it inconceivable that Gail would choose a side the way she did, the idea of leaving a mess behind, especially when there was time to fix everything before she died,” Moon says. “She always misinterpreted it as her children searching for a pot of gold that never existed. Gail felt like I was kicking her out the door, but it robbed me of the ability to grieve her loss.”

In Taos, Zappa has found some solace in the austere beauty of its mesas and snow-capped mountains. He leads meditation workshops and has created his own line of herbal teas. While he continues to admire his father’s talent (the book is dedicated to him), he is still trying to sort out his feelings about his parents. “I guess my story could be a cautionary tale about growing up in the shadow of a giant,” Zappa says. “But it’s really about overcoming something really difficult and finding peace.”

Moon Unit Zappa will be in conversation with author Ariel Leve at the Beverly Hills Public Library on August 22.