“The Testament of Ann Lee” stars Amanda Seyfried as the founder of the Shakers, a religious sect formed in the 18th century and known both for its pursuit of full social equality and for its songs and dances designed to rid the body of sin. Using songs based on actual Shaker hymns, the film's most technically ambitious and narratively rewarding scenes depict these vigorous movements as communal expressions of hunger, obedience, grief, devotion, and ecstasy.

“You can't tell Ann Lee's story without showing her adoration, and we put a lot of thought into interpreting her and creating her on screen,” said director Mona Fastvold. “We had a lot of challenges: dancing in the forest with roots and holes, in a small room with hundreds of sails, on a boat in a real storm, and we really only had half a day to film each one. But it was exciting to see how the limitations informed the movement.”

The film's Shaker dances have their roots in historical materials such as baroque and religious artworks, written descriptions of early believers, and statements by various detractors. “Their critics described in detail their 'wild' worship (how they danced for days in a row and made all these crazy sounds) and we definitely used that,” Fastvold said. “The most important thing was that all the movements had meaning. They couldn't just be cool movements; it's prayer.”

Celia Rowlson-Hall, who worked with Fastvold on 2018's “Vox Lux,” created choreography that charts the evolution of the Shakers. In scenes recounting their origins in Manchester, England, believers reach upward with hunger in their eyes, lean on each other in collective caresses and beat their chests vigorously, “almost as if they were beating the responses out of the body,” he said. “These people needed to believe in something other than what they had been given, so I wanted it to feel like a delirium of excitement, youth and fervor. It seems 'sinful,' but it's actually a very serious and honest movement.”

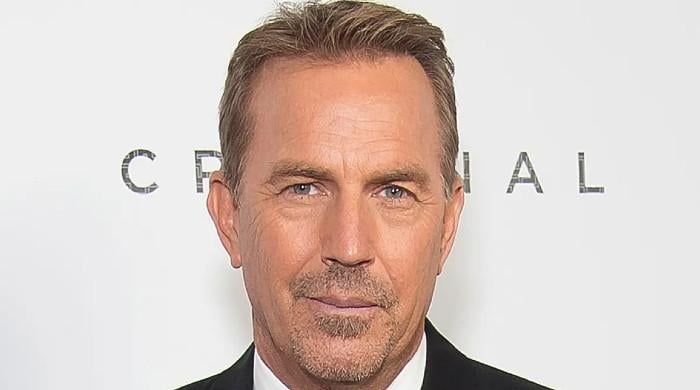

Amanda Seyfried in “The Will of Ann Lee.”

(Reflector Images)

In later scenes, when the Shakers are established and actively recruiting in the United States, the faithful march in straight lines and concentric circles, while lightly touching shoulders, crossing their arms, and looking straight ahead. “It's prayer through action, what you will do every day for your relationship with God,” Rowlson-Hall said. “The movement doesn't have to be so big anymore, because the work is already done and now there is some understanding. Instead of looking for the fire, it's more like tending to it.”

Illustrating these feelings of faith meant giving gestural cues to more than a hundred extras on set, in addition to choreographing dozens of actors and dancers. Not to mention meticulously planning the movements of the camera, which sometimes plays the role of a wallflower, observing the crowd from a distance, and at other times moves towards the center of the action, making wild pans as if it were also dancing.

“We wanted to show the beautiful shapes that Celia made, but we also wanted the camera to be one of the believers,” said cinematographer William Rexer. “I brought my iPhone to rehearsals, Celia pointed out moments of the dance that were important to capture, and we mapped out specific shots. It was that process, over and over again, of observing how the camera could become an active participant.”

One standout sequence, which intercuts the Shakers' steadfast praise throughout the seasons of their arduous journey from England to America, was filmed on Sweden's Götheborg, a fully functioning replica of an 18th-century ship. The actors danced on its narrow deck, singing as they leaned left and right to imitate ocean waves; Between takes, they changed costumes to repeat the choreography through the wind, rain and snow.

(Ian Spanier/for The Times)

“My plan for that day was to start dry and work my way to wet,” Fastvold said. “There was a real storm coming, so we started with a beautiful blue sky that actually went dark, with real rain mixing with our rain towers. We only filmed in the rain once; the actors' suits became very heavy when wet, but it had the effect as if they had stabilized their sea legs in the storm.”

At the center of these musical moments is Seyfried, executing the varied choreography with visible and unwavering conviction. “I was on the high school dance team because I enjoyed it once I learned it, but getting there has always taken me a long time and it's frustrating not being able to remember a move,” she said. “But the movements are so instinctive, grounded and human, that it's liberating to perform. And when it came time to teach the dances to the other actors, I was the person in the room who already knew them! It's the first time that's happened to me. It put me in a leadership role, which was appropriate.”

Among the group's spectacular numbers are emotional solos, in which Seyfried describes Ann's life-altering incarceration and her harrowing journey toward motherhood. “The existence of the Shakers is 100% due to these experiences,” said Seyfried, who sang live for most of the film. “When I was fighting because [the notes are] so high in the register, that push was perfect for the job. “It was satisfying as an artist to find a way to channel that discomfort as another way to honor her.”