Cinematographer Edward Lachman was beginning to think he would never be able to work with director Pablo Larraín, an old acquaintance. But more than 15 years after their first meeting, “The Count,” a satirical horror film that reconsiders former Chilean president Augusto Pinochet (Jaime Vadell) as a vile, blood-sucking vampire, has become that occasion.

After his recent Oscar nomination (along with the coveted Silver Frog award at Camerimage, the prestigious film festival), Lachman is turning heads, and rightly so. From his first painting, “The Count,” he immerses viewers in a bygone black-and-white era steeped in somber German Expressionism. Lachman cites films such as FW Murnau's “Nosferatu” (1922), Josef von Sternberg's “Shanghai Express” (1932) and Carl Theodor Dreyer's “Vampyr” (1932) as key influences on his visceral palette.

“Once Pablo wanted to go in black and white and we dealt with the gothic and vampire film genre, that became a touchstone for looking back at these German and American expressionist works,” says the born cinematographer in New Jersey, 75 years old. The envelope.

Paula Luchsinger plays a nun seduced and converted by the vampire Augusto Pinochet in “The Count.”

(Netflix)

Pinochet came to power in 1973 and, until his overthrow in 1990, kidnapped, tortured and murdered thousands of Chileans. Larraín, known for his big-screen dramatizations of real-life public figures — Princess Diana in “Spencer” (2021) and Jacqueline Kennedy in “Jackie” (2016) — turns Pinochet into an undead evil who lives in a decrepit mansion in southern Chile. for 250 years.

The terror that Pinochet inspired is a symbolic truth that generations of Chileans still struggle with today. “I didn't want the images to take you away from what the story is really about,” Lachman says. “It's about internal pain. Yes, it's metaphorical who he is as a vampire, but that's exactly what he was. He lived in the hearts and minds of these people who never received retribution or healing. Pinochet died a rich man with impunity for his crimes against the society and culture he terrorized.”

When technically creating the look, the cinematographer asked camera manufacturer Arri to build the first large format camera of its kind with a monochrome sensor. To their happy surprise, they were able to turn in the application several days before principal photography began. Delving deeper into the aesthetic, Lachman paired his newly acquired Arri Mini LF monochrome camera with a set of custom 1930s Baltar lenses, as well as a set of vintage Harrison & Harrison black and white filters.

All of this produced rich exteriors that looked foreboding and heavy even in daylight. Lachman also implemented another tool called the EL Zone System, which he created himself. It is based on a technique used by famous landscape photographer Ansel Adams as a way of evaluating exposure.

“This was the first time the system could be used on film,” says Lachman. The toolset gave him the powers of a painter with a brush, polishing shadows and highlights to a fine level of detail.

The production was filmed in six different locations throughout Chile, with a farm in Patagonia as a key setting. The interiors of the house, the hallways, the basement and the living room were first filmed on sets built in Santiago. To illuminate them, Lachman had to imagine what the outside sunlight would look like months later, when they finally moved outside.

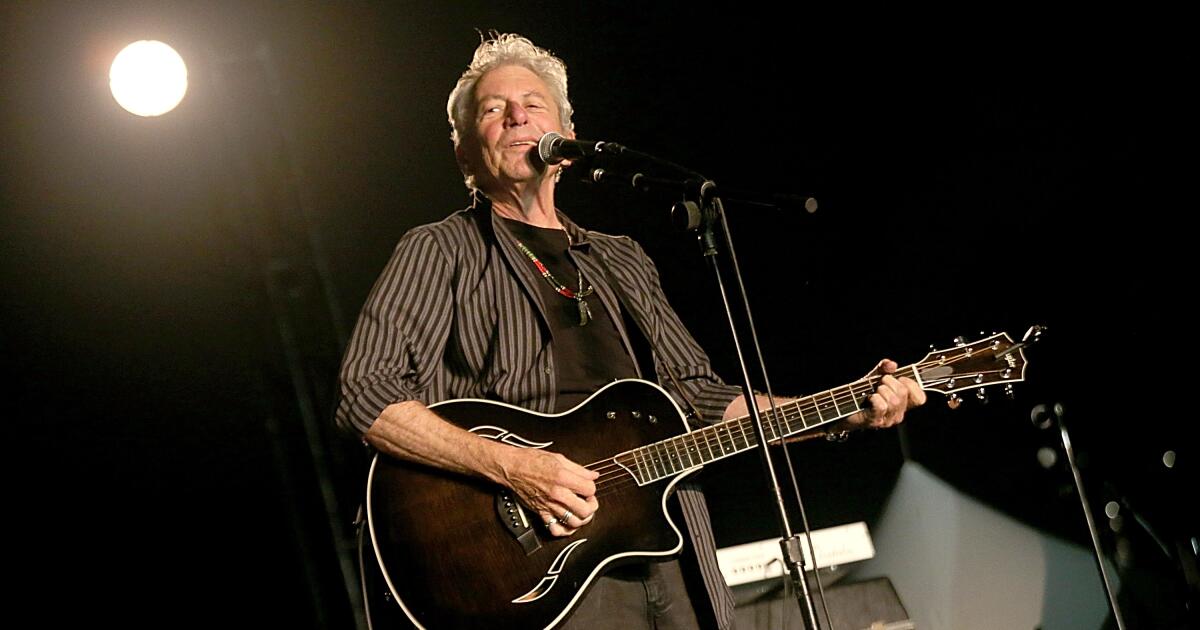

Jaime Vadell plays the titular “The Count.”

(Diego Araya Corvalán/Netflix)

“When I went to explore the outdoors, they told me it would be winter with cloudy light that could change very quickly,” he recalls. “So I papered the windows and used curtains as diffusion to let in soft light. But sometimes I made holes in the diffusion to let the lights through.” For the mansion's central living room, overhead fixtures provided the main source of lighting, while fixed fixtures like chandeliers added texture and ambiance.

For the actors, Lachman chose to keep the darkness in their eyes. “Since we were lighting from the windows, I was worried about having to use an eye lamp,” he says. “Then I realized that these people hide from themselves and from others. That there is a certain darkness that these characters live in even in the light of day. So I accepted the enlightenment that things do not reveal themselves. And what they are hiding from is the people they persecuted.”

A Technocrane was used almost exclusively to find camera positions organically. “The camera had a certain fluidity to it,” says Lachman. Scenes depicting Pinochet flying were filmed against a blue screen using a color camera and then converted to black and white. But for the flight sequence with Carmencita (Paula Luchsinger), a nun seduced by Pinochet's vampire ways, the trick was practically done, with the actor hanging from cables connected to a crane.

“The film conveys a sense of contrast between light and dark, youth and age, church and state,” says Lachman. “She is learning to fly and this power reflects those in the church hierarchy who supported Pinochet because of his own power.”

Most vampire movies are about seduction and power, but through Lachman's careful filming and Larraín's political dimension, “The Count” represents something deeper. Now that he has collaborated with the director, Lachman recognizes the suffering of Chileans. “They had their blood drained politically, socially and culturally,” he says. “We have to remind ourselves over and over again of our own failures. The pain is eternal for them.”