It only took one hour, on February 7, 1999, for American television to completely change.

That day was the premiere of “College,” the fifth episode of the new HBO drama “The Sopranos,” and the world would never be the same. Every antihero and conflicted family, every dark-as-a-night comedy and every humanized monster series that made television the preeminent art form of the 21st century, can trace their roots directly to “College.” The same goes for many of the problems that the television revolution ultimately unleashed.

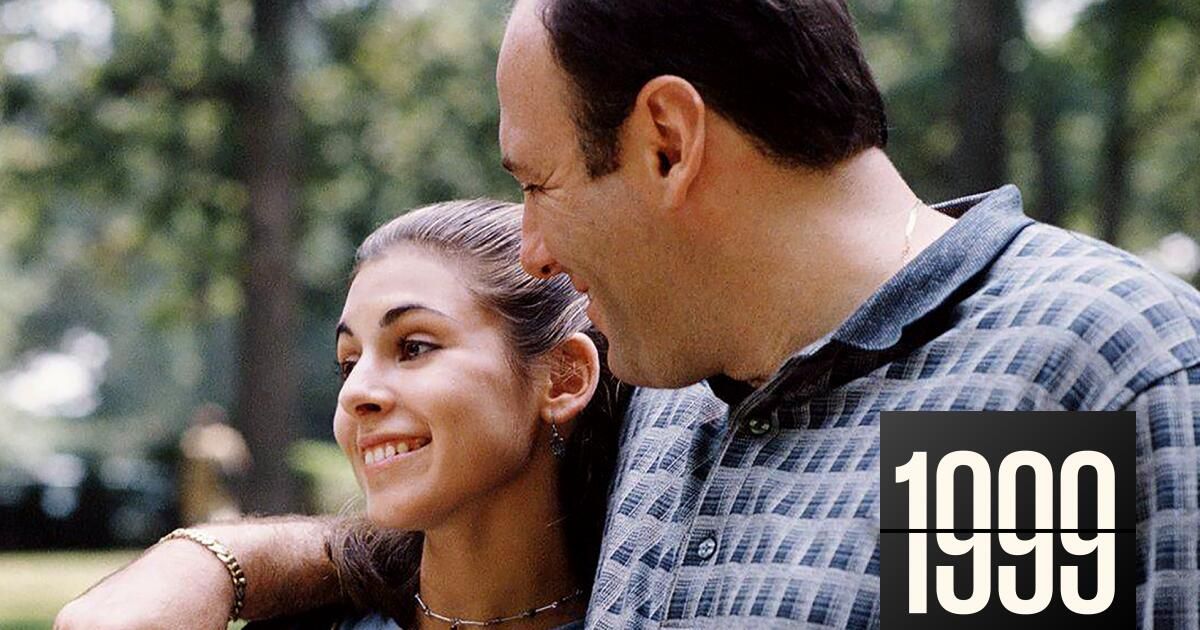

For an hour, audiences watched with their mouths open as New Jersey mob boss Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini) took his pampered but essentially sweet daughter, Meadow (Jamie-Lynn Sigler), on a college tour, only to glimpse, at a gas station, an FBI informant who imprisoned several of his friends. What followed was a horrifying but often hilarious display of working parent multitasking as Tony attempted to help her daughter sort out her future while, unbeknownst to her, ending the informant's.

With his own hands.

The 1999 project

All year long we will commemorate the 25th anniversary of the pop culture milestones that remade the world as we knew it then and created the world we live in now. Welcome to the Los Angeles Times' 1999 Project.

The television definition of a protagonist, the traditional limits of the stories the medium could tell and any notion of audience expectations went out the car window in “College,” making room for everything from “Breaking Bad” and “ Dexter” to “True Blood.” ” and “Game of Thrones.”

It's important to remember that when “The Sopranos” debuted on HBO just a month earlier, it was treated like any other television show. Yes, it received almost universally good reviews (then-Times critic Howard Rosenberg called it the “series of the season”), but in several of those reviews “The Sopranos” didn't even get the best rating. Rosenberg paired it with the forgotten NBC drama “Providence.” The late, great Washington Post critic Tom Shales dismissed the Fox comedy “The Pajamas” before promoting “The Sopranos” as a “mafia opera for people who think they've had enough of the mafia.”

HBO was relatively new to the original scripted drama game – “Oz” had premiered just two years earlier – and no one expected that a platform called Home Box Office, which proudly declared “It's not TV, it's HBO” would start a revolution in a medium that was still considered inferior to cinema, not to mention literature, theater or the fine arts.

Everyone was excited that David Chase had breathed new life into the mob drama, in part by making his main character so shaken by family tensions and a career in New Jersey “waste management” that he later After suffering a panic attack, he goes to therapy. . (Something was definitely in the air that year: In March, Harold Ramis did the same at the actual box office with the comedy “Analyze This,” starring Billy Crystal and Robert De Niro, and it was successful enough to spark a sequel.) Analyze that.

James Gandolfini in season 1 of “The Sopranos,” which premiered in 1999.

(HBO)

But anyone who thought “The Sopranos” was “The Godfather” on Prozac, or a paean to therapy as a solution to violent crime, realized, in “College,” that this was much more than a mafia opera. It was an excavation of the compartmentalized lives we all live, to one extent or another.

Minutes into their road trip, Meadow asks her father directly if he's in the mafia. Other kids don't find “$50,000 in Krugerrands and a .45 automatic pistol when looking for Easter eggs.” After some inexperienced awkwardness (“I'm in the waste management business, everyone assumes you're bullied, it's stereotypical and offensive”), he offers her a classic parental half-truth: some of his money comes from illegal gambling. “And why not.”

Like so many children who try to deal with family secrets, Meadow wants to know but she doesn't want to know either; she accepts his bland description of her violent organized crime, delighted that her father shared even that with her.

You don't have to be part of a mafia family to recognize those dynamics.

Meadow also confesses a little, revealing that she and her friends have tried speed. As expected, Tony explodes, regardless of whether part of his business involves selling drugs.

James Gandolfini as Tony Soprano, with Jamie-Lynn Sigler as his daughter Meadow Soprano.

(Barry Wetcher/HBO)

Along the way, Tony also juggles phone calls to his angry mistress and his ailing wife, Carmela, who is busy confessing her sins, while trying to compound them, with her handsome parish priest. (We're in the pre-mobile era, so this means a lot of pay phones, which inevitably adds to the tension, and also the “I have to make a call” excuses.)

When Tony sees the snitch, some of those calls go to his nephew Christopher (Michael Imperioli), turning what was supposed to be a father-daughter bonding experience into a work trip. And if the “work” involved is a little more dramatic than, say, terminating a contract, the basic tension is familiar to virtually every working parent.

Coupled with Carmela's confession to the young priest that she believes her husband has committed “horrible acts,” Tony's strangling of the informant is appropriately brutal and prolonged, removing any pretense that Tony is somehow a gentler mobster. and gentle. Previously, audiences had seen him threaten, throw punches, and even break a man's leg, but compared to some of the other characters, including his own mother, Tony seemed more human. His anxiety attacks, triggered by the escape of a family of ducks he had raised in his pool, seemed to offer evidence that, on some level, he was uncomfortable with the carnage his job required. .

In “College,” viewers were forced to recognize the brutality in the man. Tony not only sentenced a man to death the moment he saw him, he insisted on carrying out the sentence himself. With furious delight. After which he picked up her daughter from a fancy private college and lied to her face about what he had been doing, with no apparent guilt or reluctance.

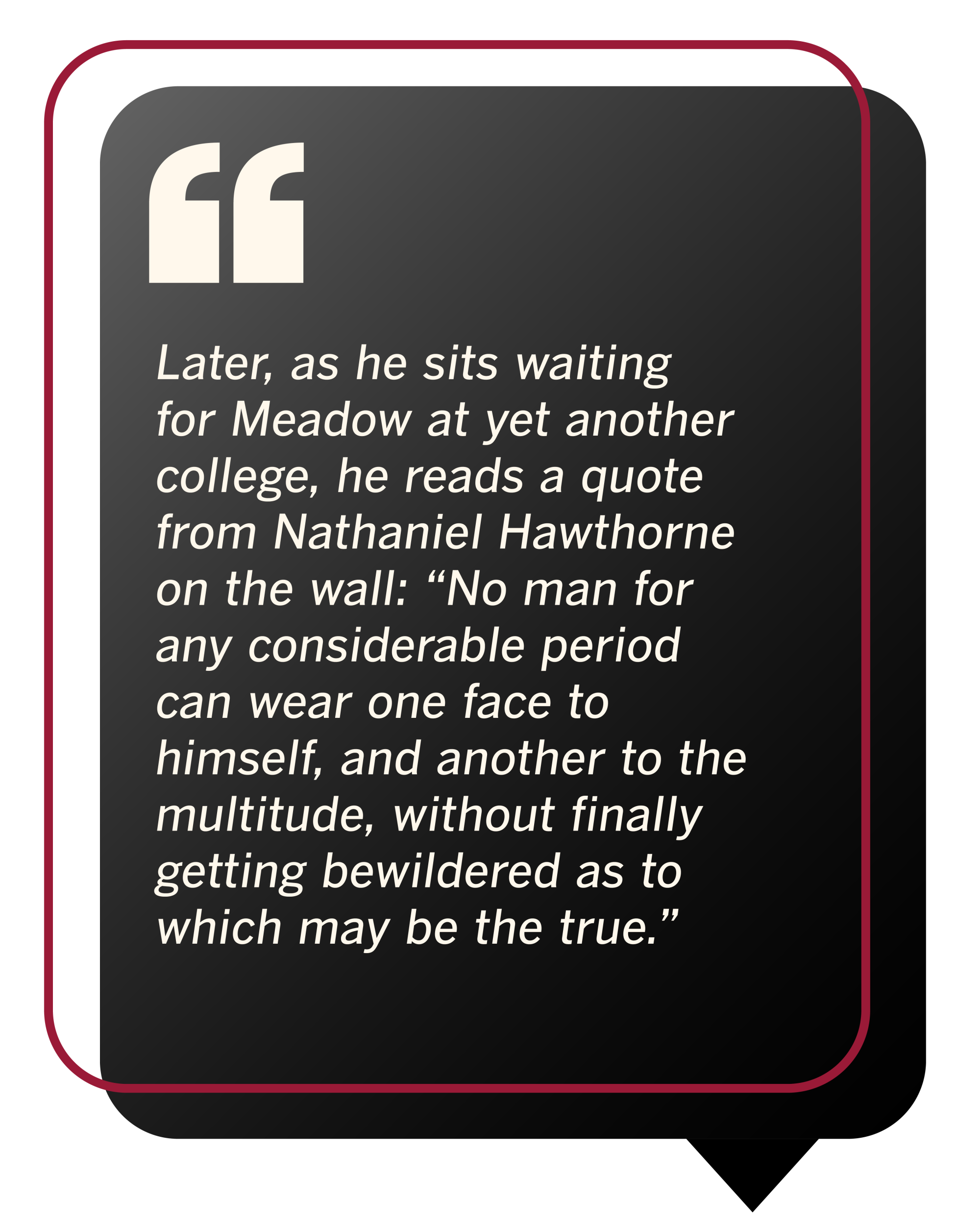

Later, while waiting for Meadow at another college, he reads a quote from Nathaniel Hawthorne on the wall: “No man for any considerable period can show one face to himself and another to the multitude, without finally becoming baffled as to what he can do.” be the truth.”

In that moment, Tony doesn't seem defiant or embarrassed, just a little sad and, perhaps, resigned. He is a man with many faces for the multitudes; It is the face that shows that remains hidden. If action makes the man, who is he really?

With their mouths open, viewers were asked to accept a different truth: that Tony Soprano is a cruel person who also deserves love and compassion, just as Carmela could be both callous toward others and desperate for intimacy. Never before has a television program demanded so much of its audience. Never before had a television writer assumed that viewers would be able to become attached to a character who in almost every other series would have been the bad guy.

Chase didn't mess around and we loved him for it. In Tony Soprano, many people saw a modern everyman. Born into a toxic family, wanting a better life but unsure how to get it, conscious enough to suffer panic attacks but unable to truly change, his tears over the ducklings that flew away were as real as the satisfaction he felt from suffocating to the lives of another human being.

Whether or not you admire the series of humanized antiheroes and monsters that followed Tony Soprano (and you could argue that by loving Tony, we justify the worst in ourselves), the exquisite writing and acting of “College” proved that Television can ask the same questions, offer the same ideas, disrupt predictable thinking as well as all other art forms. Even after 25 years, the episode remains a revelation. You can watch it without having heard of “The Sopranos” and still be mesmerized. As if it were a poem. As if it were a painting.

As proof, once and for all, that no story, neither character nor circumstance, had to be limited just by being on television.