The best thing would be to wake up and find yourself in bed in a Chicago apartment with Bob and Emily, or in a Vermont inn with Dick and Joanna, and discover that this was all a dream. Unfortunately, the world doesn't work that way. Bob Newhart has left the stage for the last time and the dream is over.

Newhart, who died Thursday at 94, was a quiet comic giant whose stealthy genius dominated comedy for seven decades and whose name was associated with four great sitcoms: “The Bob Newhart Show,” “Newhart,” “Bob” and “George and Leo” — his first name George, already a drinking game, “Hi, Bob.” (Excuse me while I take a sip.)

After a brief, unsuccessful stint selling recorded comedy routines to radio stations, his first album, “The Button-Down Mind of Bob Newhart,” recorded in 1960 at his first public performance, was a massive, historic success: it reached No. 1 on the Billboard charts and won Grammy Awards for Album of the Year and Best New Artist. When his next album, “The Button-Down Mind Strikes Back!,” was released six months later, Newhart found himself with No. 1 and No. 2 records in the country.

In the early 1960s, comedians didn't talk about themselves the way they do now; authenticity wasn't valued as a quality comedy. They worked behind created characters or put on little skits; this was as true of Lenny Bruce as it was of Nichols and May or Shelley Berman (who, like Newhart, employed the one-sided telephone conversation). They could show you who they were by the way they processed the world in a routine; Newhart estimated that his character “is about 85% me, the other 15% is an extremely… sick mind that enjoys the macabre.” But they wouldn't draw you a picture.

There is no “I” in Newhart’s classic monologue, beyond “I was reading in the paper today” or “I think it might be something like that.” All you can tell about him from his stage performance is that he was from Chicago, worked as an accountant (“He had some kind of weird theory of accounting: if you got within two or three dollars… but it never caught on”), and had a job at the unemployment office until he realized he made only $10 more than his clients, “and they only had to come in once a week.”

Newhart was, apparently, if deceptively, the very picture of mid-20th-century American normality: a blank canvas on which he painted his characters. He could plausibly be a driving instructor, a rocket scientist, or Clark Kent trying to get his Superman suit out of the dry cleaners; he addressed an implied partner who sat invisibly beside him or on the other end of an imaginary telephone line. (“The audience participates,” he told one interviewer, of the spaces the listener filled in. “In McLuhan’s terms, it’s not a cold medium, it becomes a hot medium.”)

Bob Newhart was, apparently, though deceptively, the image of mid-20th-century American normality, with short hair and a suit and tie, our critic writes.

(Associated Press)

In these routines, he was often calming someone down, or reassuring them, or putting a good face on bad news. He played a cop coaxing a ledge diver (“You know you’re drawing one hell of a crowd for a workday”), an analyst with Benjamin Franklin as a client (“Okay, Ben, let’s see if we can’t get to the bottom of this kite-fixation thing”), or a public-relations agent advising Abraham Lincoln before the Gettysburg Address (“You changed 487 to 87? Abe, that’s supposed to be a catch. . . . We did a test market and they went nuts”). A jarring but unwavering equanimity was a hallmark of his career, from his stand-up work to his sitcoms to his numerous guest appearances.

His role as a switchboard operator was fully inserted into his first film, the 1962 war movie “Hell Is for Heroes,” where he appeared as comic relief alongside Steve McQueen, Bobby Darin and Fess Parker. To distract eavesdropping Germans, he pretends to talk on a field phone to a superior officer: “About morale, sir, it’s been pretty low. The main complaint seems to be about the night’s movie… I’ve had to show ‘The Road to Morocco’ five nights in a row, sir… The men are beginning to get a little cranky.”

The cultural impact of a long-running show in an era when three networks owned the show and churned out two dozen or so episodes a year cannot be understated. And Newhart had two of them, both on CBS: There are 142 episodes of the impeccable “The Bob Newhart Show,” which ran from 1972 to 1978, where he played psychologist Robert Hartley opposite Suzanne Pleshette, and 184 of “Newhart,” which ran from 1982 to 1990, where he played innkeeper Dick Loudon opposite Mary Frann. (I’m also a fan of the less successful “Bob,” with Newhart as a greeting-card artist, and of “George and Leo,” which paired him “Odd Couple”-style with Judd Hirsch.) Sitcoms are not just shows to watch but places to go; we live alongside the characters, through time. We react to the comedy so strongly because we know them so well, we know where they're going, what they mean. Bob was family.

For all its mastery of one-sided conversation, “The Bob Newhart Show” proved that its star’s true artistry emerged when he had other actors to interact with and react to. Audience expectations meant that phone calls were always necessary: A drunken phone call to a Chinese restaurant trying to order moo goo gai pan is one of the series’ signature moments. On both “The Bob Newhart Show” and “Newhart,” as a relatively sensible person beset by eccentrics, he could get a lot out of a simple “Why?” His version of a double take was a blank stare, and his weapon, the wry passing comment.

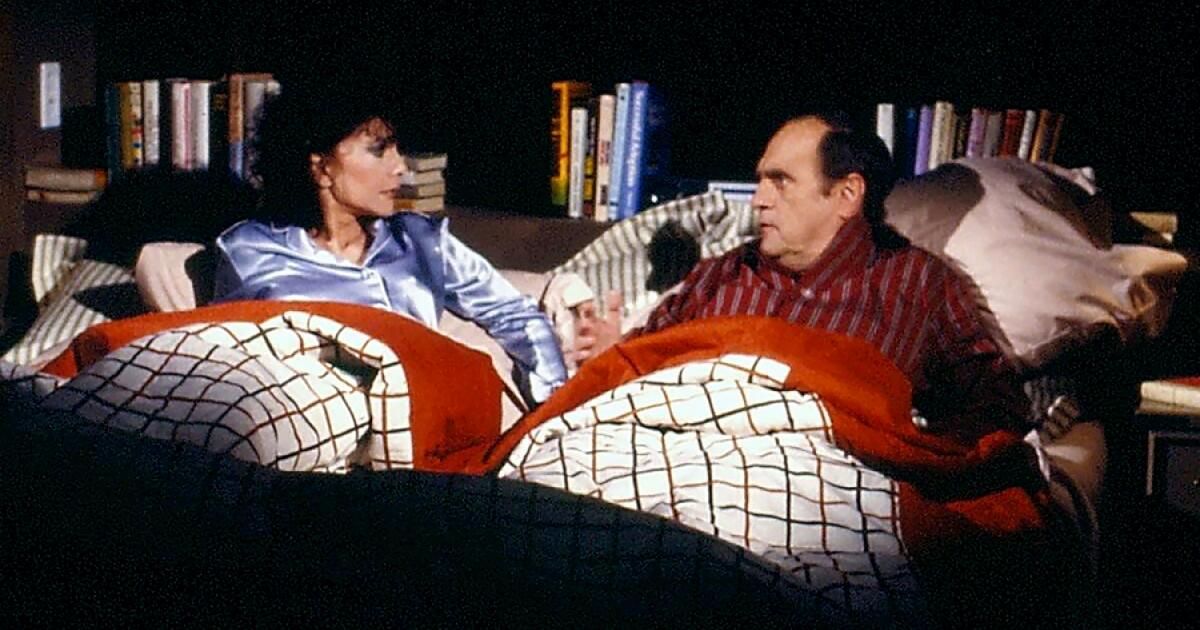

Relatively few sitcoms were interested in adult married couples when “The Bob Newhart Show” came on the air, and especially one without the baggage of children. The Hartleys and the Loudons were not free from irritation or annoyance in their relationships, but they were attractive, attracted, sexual-by-implication people. Bob and Emily not only shared a bed, which was awfully modern for 1972 television, but the bed was a stage; some of their best comedy was played out on it, lying side by side. When “Newhart” suddenly morphed into “The Bob Newhart Show” in its famous final moments, suggesting that the entire subsequent series had been Bob Hartley’s dream, it was to that bed that he magnetically returned. The studio audience began applauding as soon as the stage (which had been kept secret from cast and crew) was revealed, even before Pleshette rose from under the covers.

Aside from late-career dramatic roles, Newhart brought the same comedic tools to every job, whether as Will Ferrell’s adoptive father in the perennial Christmas movie “Elf” or as Jim Parsons’ childhood idol on “The Big Bang Theory.” Because he was demanding, or lucky enough to work with writers who knew what to do with him, or simply because he was so good, so completely himself, it’s hard to find a failed appearance at any stage of his long career. “Catch-22” may have been an odd movie by the book, but there’s nothing wrong with Newhart’s Major Major Major.

His timing was exquisite, his delivery musical, light and dry (he didn’t like being called “deadpan” or “mild-mannered”). The fact that he started out in radio as “a poor man’s Bob & Ray” perhaps honed him in on the power of the pause, the uses of silence. His natural tendency to stutter—“which I think is a sign of intelligence, but I can’t find evidence to support it”—was inherent in his intermittent speech. One breath before the end of a sentence turned the last word into a firecracker.