As a boy growing up outside Manchester, England, John Mayall recognized something personal in the blues records coming out of the United States. He heard joy, agony and real-life stories, all set to music that could be euphoric and downtrodden, hopeful and mysterious.

It was music of deep emotion that would stay with him forever, and as one of the main drivers of that tradition in the British blues explosion of the 1960s, he represented a role model for many better-known musicians. “He was my mentor and also a surrogate father,” Eric Clapton said in a tribute posted Wednesday on Instagram. “He taught me everything I really know and gave me the courage and enthusiasm to express myself without fear or limits.”

Mayall, who died this week aged 90, provided a home for an astonishing lineup of virtuoso musicians who passed through his band the Bluesbreakers on their way to greater fame later: Clapton and Jack Bruce (who formed Cream), Mick Taylor (later of the Rolling Stones) and members of Fleetwood Mac, Journey, Canned Heat and more.

John Mayall was a mentor to Eric Clapton, Mick Fleetwood and many other superstars.

(Claus Hampel / Associated Press)

He was half a generation older than many of the iconic musicians he mentored and a major source of inspiration. He gave refuge to a disheartened Clapton, who had just left the Yardbirds and was considering giving up music altogether. But the fame later enjoyed by many of the musicians who toured endlessly with Mayall had nothing to do with him.

“The big list of the most famous names came out of that four- or five-year period in London,” he told me in 1997. “Everyone knew each other, so they were moving around, finding their own musical path. As a bandleader, I would hire anyone who caught my eye. That criteria is the same today as it ever was.”

In the 1990s, I interviewed Mayall several times, including at his home in the San Fernando Valley. Our first phone conversation was cut short by him after about 15 minutes, probably due to my own inexperience as an interviewer and for asking too many questions about his more controversial statements (such as calling Led Zeppelin “a parody of the blues”).

But he was usually a patient proselytizer of the blues. While his own reputation was often based on his role as a profoundly gifted talent scout, his own records showed a consistent commitment to what had first inspired him. Mayall was a singer and multi-instrumentalist (harmonica, keyboards, guitar), and like his heroes, the songs he wrote were autobiographical: celebrations and laments about his life experiences.

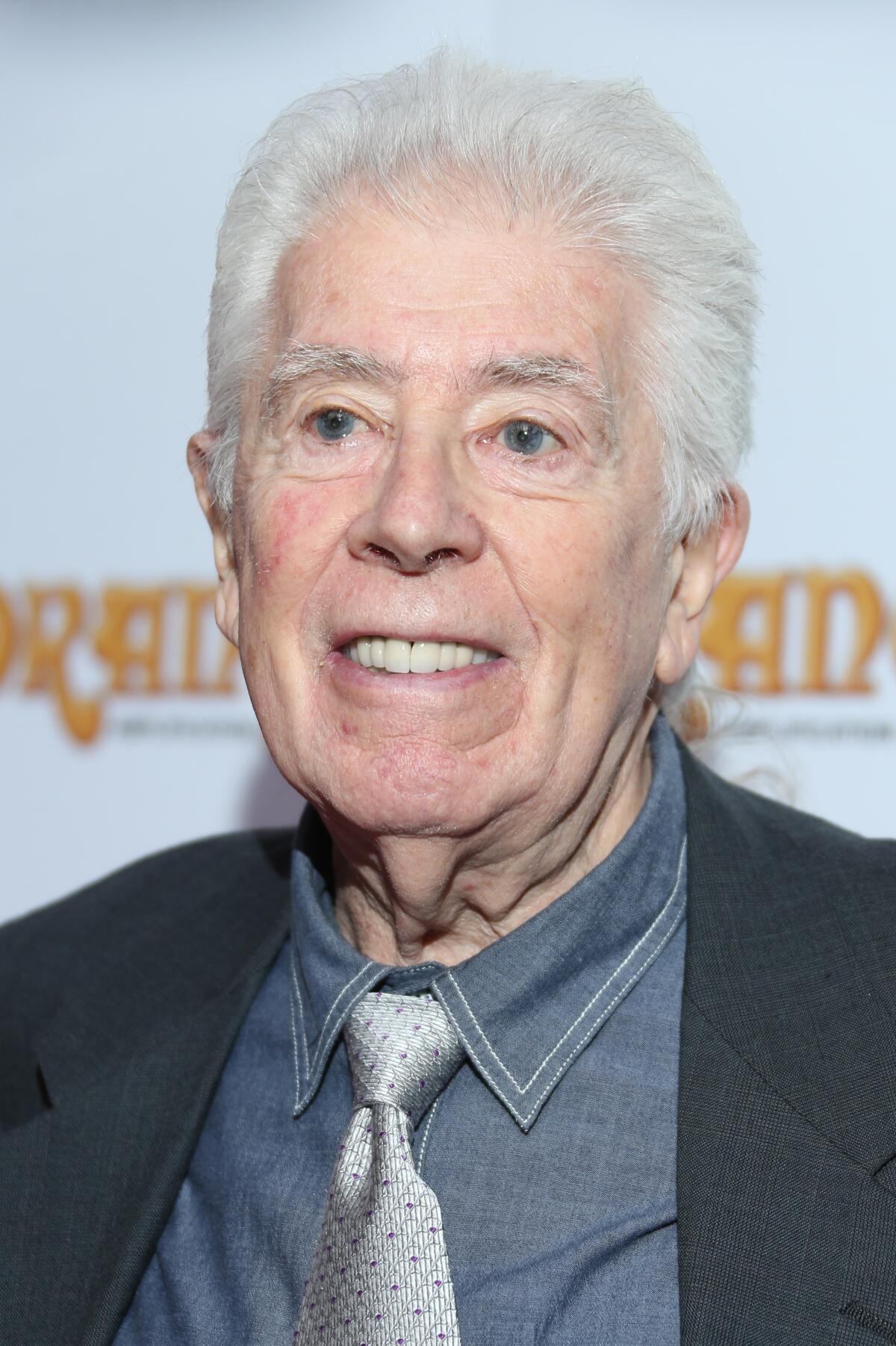

John Mayall at the 2013 Classic Rock Roll of Honour awards in London.

(Joel Ryan/Invision/Associated Press)

He was sometimes criticized as a purist who rarely wavered, even as his former collaborators received praise and recorded hit records dabbling in rock, psychedelia and pop. If anything, his experiments moved even further away from the mainstream with a jazz-rock fusion sound on 1968’s “Bare Wires.” He stretched out with layers of horns and flute, went acoustic solo, but the electrified Chicago blues was always his North Star.

“'Purist' is a funny word, actually, because it can refer to someone who doesn't want to stop making note-for-note copies of things other people have done in the early days,” he said. “There are bands that just do that. They consider themselves blues purists. But I've always been an innovator, so purist doesn't really fit.”

“I draw inspiration from the pure roots of the blues to create something very contemporary and very personal.”

Mayall grew up in the late 1940s and 1950s listening to his father’s vast record collection, learning to appreciate the Mills Brothers, Charlie Christian and Lonnie Johnson, and soon saving up to buy his own 78 rpm records. “Anything with the word ‘boogie’ on it, I bought,” Mayall told me. Then he discovered the immortal blues played by Big Bill Broonzy, Blind Lemon Jefferson and Sonny Terry.

He was already 30 when he left Manchester for London, after a career in typography and art, keen to join the emerging blues scene there. “It all happened suddenly and everyone came to London,” he said. “The Animals came from Newcastle, Spencer Davis and Stevie Winwood came from Birmingham. If you wanted to play, you had to start and establish yourself in London. So that’s what I did.”

The British blues scene was ushered in by Alexis Korner and Cyril Davis, and evolved from folk clubs to the electrified blues of Chicago. As with Mayall, American blues had reached the post-war generation in the British Isles and ignited a movement, even as the blues were still little appreciated in the US. It would take a British invasion of inspired young musicians to bring it back home.

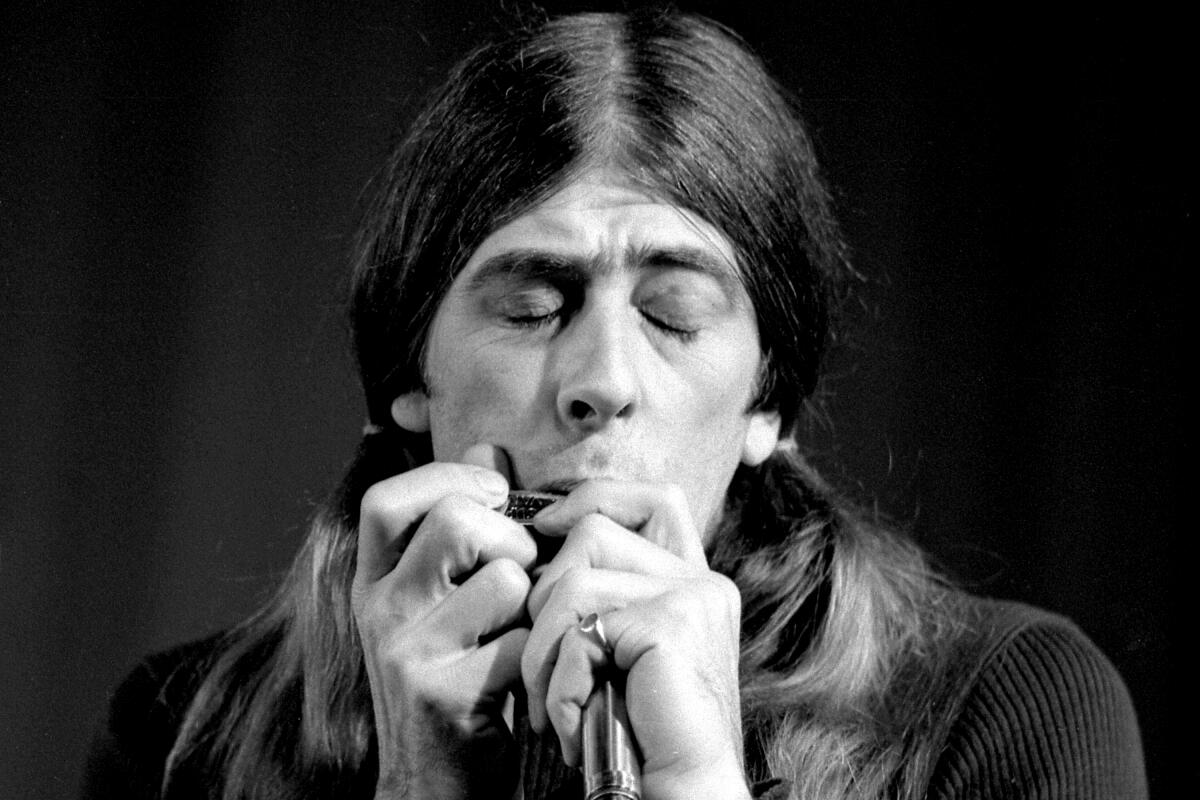

Mayall was a singer and multi-instrumentalist (harmonica, keyboards, guitar) and, like his heroes, the songs he wrote were autobiographical: celebrations and laments about his life experiences.

(Claus Hampel / Associated Press)

In those early days, Mayall was encouraged by the successes of the early Rolling Stones and Yardbirds. “I was quite surprised, because I’d been playing this music privately for 15 or 20 years and I knew what it was about. But I never dreamed it was fit for public consumption, so to speak,” he said. “I owed it to myself to try.”

His best-known album, 1967's Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton, is considered a classic document of that scene and an early sign of Clapton's ever-evolving abilities. Mayall had no major pop hits and received few accolades for most of his life, apart from a couple of Grammy nominations. In 2005, he was awarded an OBE (Officer of the Order of the British Empire) by Queen Elizabeth II, and this fall he was to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with an Influence Award.

At times during interviews, he complained about a lack of recognition, but his focus was on the work ahead: spending a third of the year on the road and releasing nearly 40 studio albums and more than 30 live recordings over the course of his life. For him, his musical journey was always open-ended, right up until his final performance in February 2022 in San Juan Capistrano.

“Creating music is an art,” he explained. “Jazz and blues musicians’ careers don’t end until they die. It’s built into their longevity. It’s not a passing thing. The years just make you more mature, you learn more and more as the years go by.”