“So are you going to go have another beer in this beautiful light? Let’s see what the light looks like.”

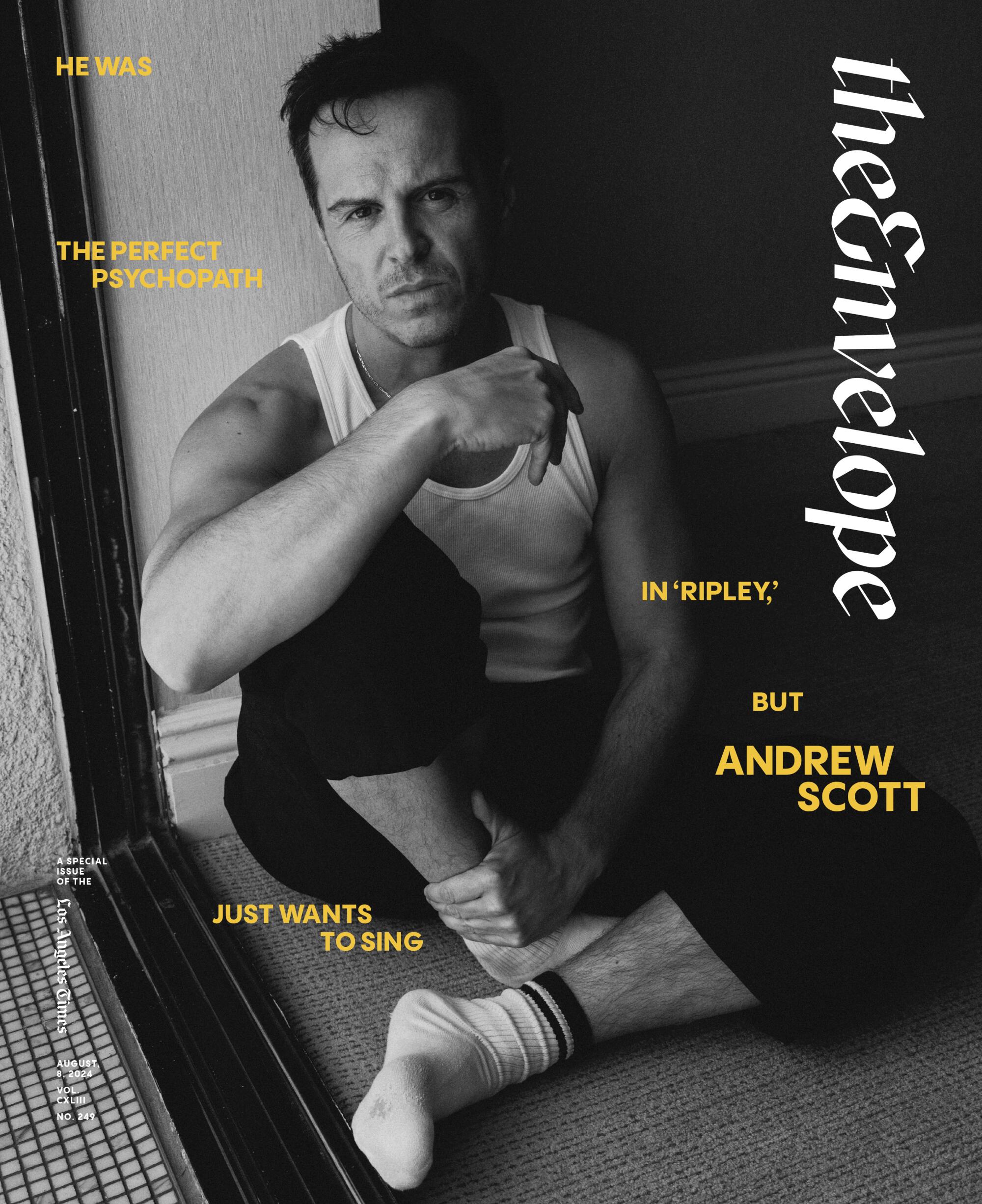

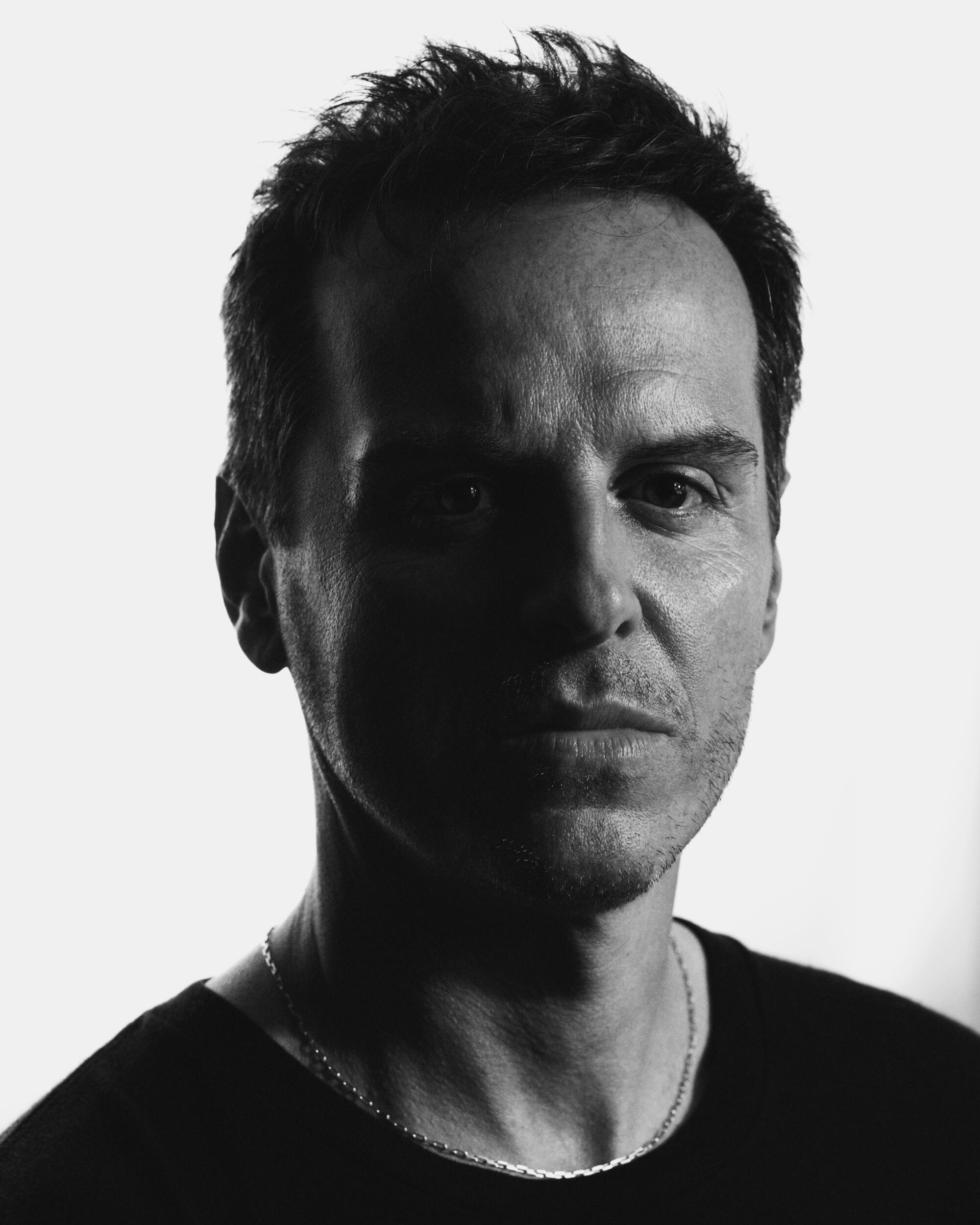

Andrew Scott walks over to the window. It’s early afternoon. Early summer. We’ve been talking for more than an hour at Sunset Studios, where Netflix has set up a space for the Emmy FYC. To be clear, Scott hasn’t been drinking. Maybe later. He’s joining a panel for “Ripley,” the streaming platform’s acclaimed adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s crime novel “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” in which he plays the cunning, hard-working psychopath of the title. Me? I’m going to take advantage of the already-open bar.

The Dublin-born actor has already visited Los Angeles eight times this year, and while he loves hiking in the canyons and swimming in the Pacific, what he finds extraordinary about the city is the quality of the light at this time of day, the last hour before the sun sets over the ocean or, in the direction we are now looking, the Hollywood Hills.

“There’s nothing better than going for a walk at the end of the day in Los Angeles,” says Andrew Scott. “I like a good walk. You need nature. You just need it.”

(Ryan Pfluger/For The Times)

“When you go for a walk at the end of the day in Los Angeles, there's nothing like it,” Scott says. “And I know people don't walk much here and they definitely think I'm…” He pauses, searching for the right word. “Like, almost angryBut I walk a lot here. I like walking. You need nature. You just need it.”

There's something else Scott needs right now. Maybe needs It's a bit of a stretch. But while making the promotional rounds for his Emmy-nominated lead actor role in “Ripley,” Scott took every opportunity to defend his stance that he's been taken too seriously for too long as an actor (not that he's complaining) and that what he'd really like to do is… Let the fanfare sound — star in a musical.

“Yes, I have,” Scott says, laughing when I point out all the lobbying he’s been doing. “What can I say? When I was a kid, I loved watching musicals on TV and singing along. I think it’s just a joy. And I feel like I have good access to joy in my life.”

“I love romantic comedy… a good comedy is absolutely joyful. And I love to laugh and have a good time,” says Andrew Scott, clearly keen to tone down his work.

(Ryan Pfluger/For The Times)

If you saw the video of Scott at one of Taylor Swift’s eight London shows in June, wearing a black tank top and dancing to “Shake It Off” with his “Fleabag” co-star Phoebe Waller-Bridge, you know it’s true.

“I’m trying to convey that energy,” Scott says. “You’ve seen it. Why wouldn’t anyone else see it?” He pauses and laughs out loud. “But I love romantic comedy. I think a good comedy is absolutely joyful. And I love to laugh and have a good time.”

Scott has shown flashes of that throughout a career that has seen him play a villain who gleefully embraces anarchic chaos (Moriarty in “Sherlock”), a seductive, boyish priest whose heart belongs to God (“Fleabag”) and a lonely writer who begins a passionate relationship with a neighbor just as he is reconnecting with his mother and father, parents who died in a car crash when he was 11 (“All of Us Strangers”). He has also played Hamlet on the London stage and, last year, all eight characters in a one-man adaptation of Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya.”

So if he wants to do a musical, who can doubt him? Scott simply likes, as he puts it, “changing the dynamic,” constantly shifting moods and mediums, which probably means he won’t be playing Ripley again, though the series finale does delightfully raise the possibility of further adventures.

“The ending is beautiful,” Scott says. But in a way that “leaves you wanting more”? “Yeah, that’s the thing.”

Andrew Scott plays con artist Tom Ripley, who becomes a total sociopath by the end of “Ripley.”

(Courtesy of Netflix/Netflix)

“The reason Ripley is so enduring is that Patricia Highsmith allows you to imagine what it’s like to be Tom Ripley, a killer, rather than inviting you to imagine what it’s like to be a victim of Tom Ripley,” Scott says. “When you put someone like that as a protagonist rather than an antagonist, it’s interesting because that side of us exists. I’m not saying we’re all killers, but it’s human to have that darkness inside of us and it’s not healthy to deny that part of us.”

He smiles mischievously: “Or, to put it another way: it’s better to pretend to hit someone over the head with an oar than to actually do it.”

We talked about “All of Us Strangers” and how I sat next to writer-director Andrew Haigh at a Telluride Film Festival screening the night after I saw his film and asked him, “Is anyone alive at the end of your movie?” Because you could argue that the film’s nearly empty apartment building serves as a stand-in for purgatory.

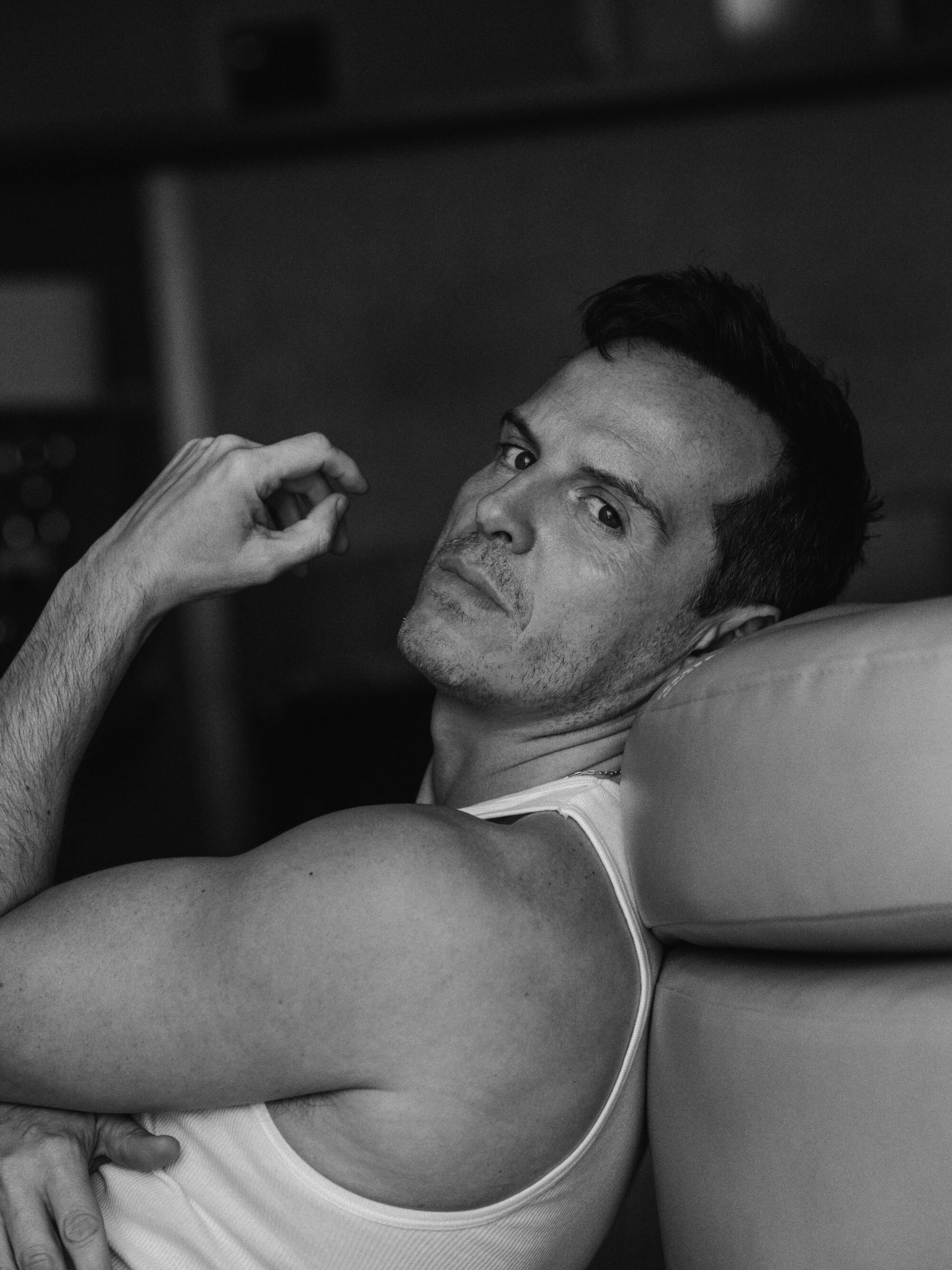

“It’s interesting that we don’t talk about death as a society because we think it’s morbid,” says Andrew Scott.

(Ryan Pfluger/For The Times)

“That’s not how I saw it, but I’m always fascinated by the superiority of the audience’s interpretation of things,” Scott says. “I remember all the suggestions about what the fox motif in ‘Fleabag’ was supposed to represent. The angel of death? Wow! Really? But I love that one work of creativity can give rise to so many other forms of creativity.”

Talking about “All of Us Strangers,” a film that Haigh says is about the ways grief and loss encompass so much of our everyday existence, is very painful for both of us right now. Scott lost his mother, Nora, in March after a sudden illness; I have a dear friend who is about to enter a hospice. She asks me about my late mother (Scott possesses a curiosity born of a need to understand things and make sense of them) and how I process grief now, nearly a quarter-century after her death.

“It’s interesting that we don’t talk about death as a society because we think it’s morbid,” Scott says. “Maybe I’m just interested in it right now. I find myself asking about other people’s experiences. Maybe I wasn’t that curious before because it wasn’t a necessity. And now I see it and I think talking about it increases compassion.”

The actor is currently reading about faith and grief.

(Ryan Pfluger/For The Times)

“Do you believe in coincidences?” I ask. “In many of your projects, in particular “All of Us Strangers,” but also “Hamlet” and “Vanya,” you played characters dealing with grief.”

“It hasn’t escaped me,” Scott says. “When I was doing those things, I was imaginatively experimenting with my own life. ‘What would it be like if I was in great pain?’ ‘What would it be like to lose my parents?’ And now I’ve lost my mother. Does that make that experience any less authentic? No. In fact, it’s helped me.”

“One of the great consolations I have is that the last movie my mother saw was [the filmed version of] “‘Vanya’ because I know she saw me and knows the depth of my love for her because I channeled it into that role,” Scott continues. “Her last voicemail to me was her reaction to that play, and it’s amazing to have that.”

Nora’s influence on her son’s life was enormous. She introduced Scott to acting and art; drawing and painting have remained his passions throughout his life. “She left me an enormous fortune, an emotional fortune,” he says. And now she has gone to what he, like Hamlet, calls the “undiscovered country from which no traveller returns.”

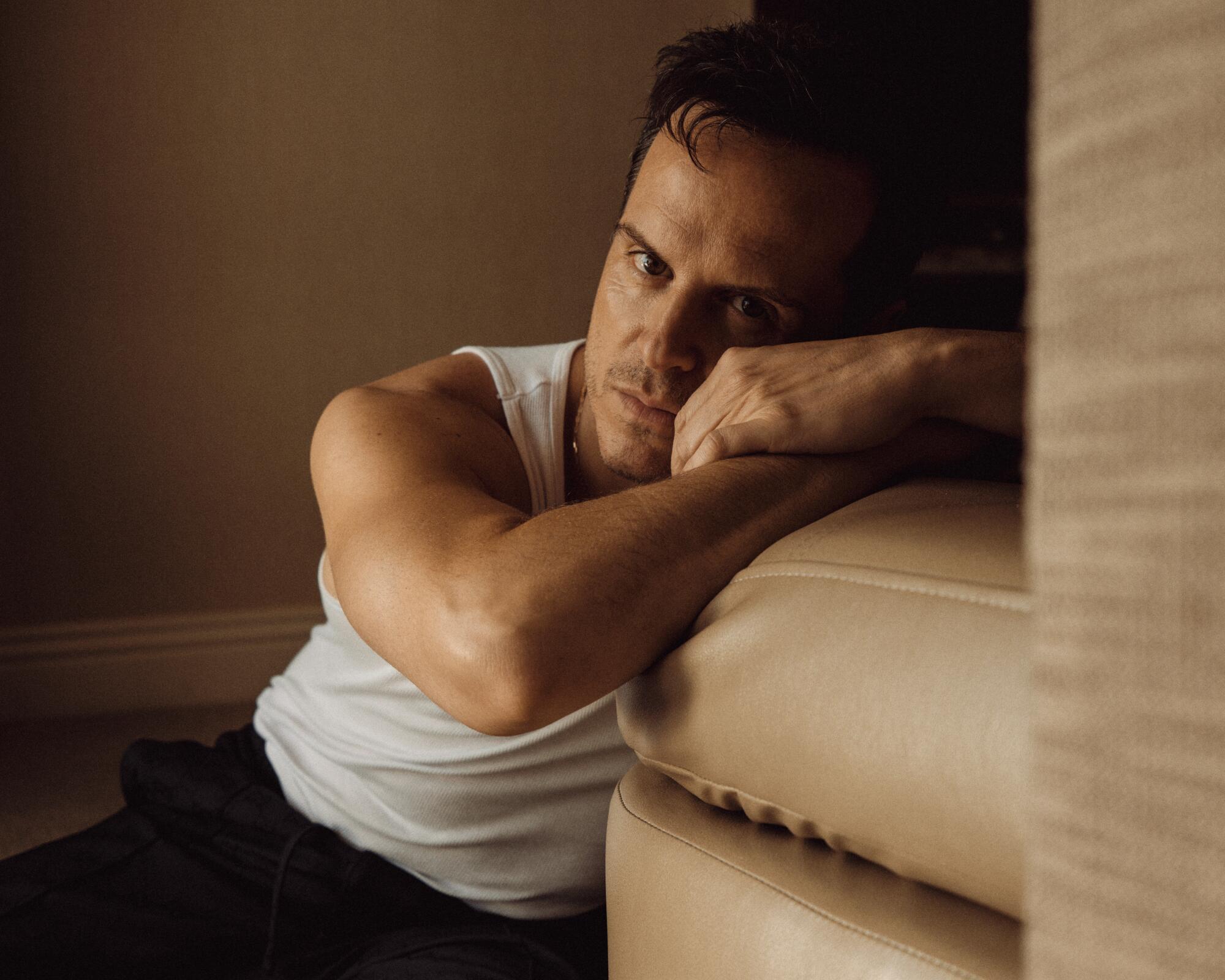

“Why not have faith in something?” Scott asks. There’s nothing to lose if you do.

(Ryan Pfluger/For The Times)

What do you imagine that country would be like?

“I'm trying to read a lot about that at the moment, and the idea of faith, the idea of holding on to something,” Scott says, telling me he's reading C.S. Lewis's “A Grief Observed,” a collection of essays about grief, doubt and faith that he wrote after the death of his wife, Joy Davidman.

“You know, if you believe in something and it turns out not to be true, then, well, okay. But if you believe in something and it turns out to be true, then, great. Why not have faith in something? And it turns out that I do have faith in something. I definitely believe in things that can’t be seen or felt. You know what I’m saying?”

Sure, I say. There’s a verse in the New Testament: “Faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.” Scott grew up Catholic and recites the verse with me.

“I think it’s very moving to have faith,” Scott says. “Like the idea of love. How do you define it? Like someone saying, ‘Show me proof of love.’ Because that person, what, bought you a car? Because you spent 40 years with them? None of those things are proof of love. Love is something you just feel and sense and it’s a spiritual thing. A lot of us still have faith in love, even though you can’t see it. I believe in love. I really do. I don’t have any degree of shame or embarrassment or shyness because I believe, deep down, in the power of love.”