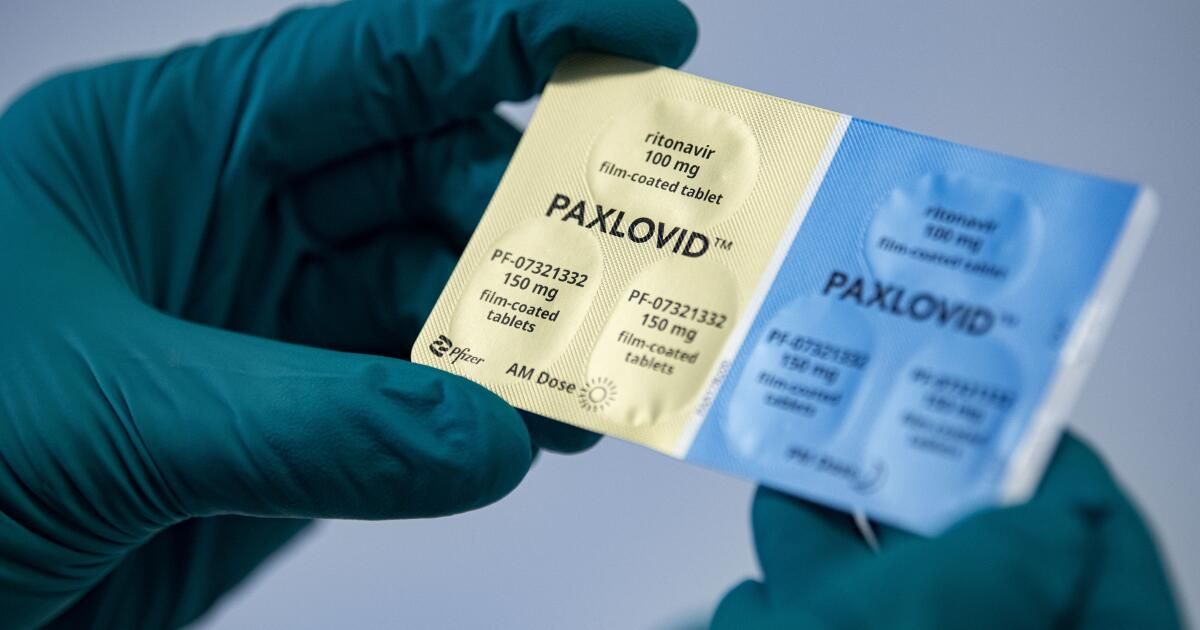

As the toll of the COVID-19 pandemic continued to rise, health officials praised antiviral drugs like Paxlovid as an important way to reduce the risk of serious illness or death.

However, studies have found that the drugs remain underused. In Boston, a group of researchers wanted to know why and what could be done about it.

Their new findings, released Thursday by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, suggest that some vulnerable patients were not offered prescription medications at all, and that doctors need more education to make sure they medicines reach patients who could benefit.

Researchers from the VA Boston Cooperative Studies Program dug into Veterans Health Administration records to take a closer look at what happened to high-risk patients who never received Paxlovid, remdesivir or molnupiravir. They focused on 110 patients who received organ transplants or had other medical conditions, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia, that would likely leave them immunocompromised and therefore at higher risk of contracting COVID-19 despite being vaccinated.

Their analysis in the CDC's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report found that 20% of those patients refused medications when offered. But the remaining 80% of patients were never offered that treatment.

In some cases, medical providers decided not to give patients COVID-19 medications because they were concerned about how they might interact with other medications patients were already taking, including cholesterol-lowering statins and a drug used to lower cholesterol. risk of a transplanted organ. would be rejected. In other cases, doctors objected because their patients had experienced COVID-19 symptoms for more than five days beforehand, beyond the recommended period for receiving Paxlovid.

Despite public alarm about “Paxlovid rebound,” in which symptoms reappear after treatment, none of the medical records mentioned it as a reason for not giving the drug, the study found. But in nearly half of the cases where people were not offered the medication, medical providers gave no reason other than patients having mild symptoms, the researchers found.

But people with mild symptoms in the early stages of their disease are “exactly the target group for treatment,” said Dr. Paul Monach, director of the rheumatology section of the Veterans Affairs and Boston Healthcare System. lead author of the study.

The drugs are recommended for people with mild to moderate COVID-19 who are at high risk of becoming seriously ill because of their age or medical conditions — the same type of patients the Boston researchers were looking at. The CDC urges doctors to treat high-risk patients within five days rather than waiting for their symptoms to worsen.

“Every case starts out mild” and it's unpredictable whether they will become more severe, said Dr. Davey Smith, an infectious disease specialist at UC San Diego who was not involved in the study. “It may not be until the fifth or sixth day that you have problems, and by then it may be too late to take these medications.”

Smith said he was especially alarmed that people whose immune systems were weakened were not receiving the antiviral drugs. “Those are the people who still come to our hospital. And those are the ones who are dying. … It breaks my heart every time I see them in the hospital and they just didn't get the medication.”

It breaks my heart every time I see them in the hospital and they just didn't get the medication.

— Dr. Davey Smith, infectious disease specialist at UC San Diego

The Boston researchers said their findings suggest that doctors need more education about when to consider using the medications. In turn, patients could be encouraged to see healthcare providers as soon as possible after they start showing symptoms.

Monach added that some Veterans Health patients who were not offered medications had gone home before their coronavirus test results were returned. Clinical staff, such as nurses, had called them to follow up, but did not appear to have mentioned the possibility of taking antiviral medications, according to records reviewed by researchers.

“That doesn't mean people weren't doing their jobs,” Monach said, “but I don't think those people would have been informed, as part of their normal jobs, what the indication would be for administering Paxlovid.”

Concerns about Paxlovid and other COVID-19 drugs not reaching patients who could benefit have persisted since shortly after the drugs became available. Just months after Paxlovid received emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration, a national survey by the COVID States Project found that among people infected with the coronavirus between May and early July 2022, only the 11% reported taking antivirals. Among a group of people at higher risk (those over 65), the rate was 20%, “higher, but still low.”

Another study of patients in the Veterans Affairs health system found that as of early 2023, less than a quarter of outpatients who tested positive for coronavirus infections were receiving any type of anti-COVID medication. And researchers have also found alarming gaps in who receives Paxlovid, with black and Latino patients getting such treatment at notably lower rates than whites and non-Latinos, even among immunocompromised patients.

“I've been banging my head against the wall because my colleagues don't use medication,” Smith said.

If doctors or patients are worried about “rebound,” he said, “COVID has this waxing and waning of symptoms anyway,” whether medications are taken or not. “And we know that this drug, in higher-risk people, prevents people from having to go to the hospital and prevents them from dying.”

A patient recently told him, “'Well, the last time I got COVID, I didn't take the medication and I was fine,'” Smith said. The problem is “that's true until it's not.” You can only dodge the bullet a limited number of times,” and the risks increase for an individual as he ages. “Every time you get COVID, you do it at a time when you are older.”

Last month, the California Department of Public Health issued a notice to doctors and other health care providers, lamenting the underuse of such medications despite an “ample supply.” He blamed a lack of familiarity with the new drugs and a misperception that drugs were in short supply.

“Once an individual is diagnosed with COVID-19, early treatment with antivirals is the only existing strategy to reduce the risk of severe illness and prevent hospitalization,” the state agency said. “The greatest benefit of antiviral treatment is seen in those who are at highest risk of severe disease. …The risks, including rebound from Paxlovid, are minimal, especially compared to the benefits.”

Dr. Richard Dang, assistant professor of clinical pharmacy at USC, said “it's always worth having a conversation” about whether to take Paxlovid or another antiviral when someone tests positive.

Medications are most effective for people at high risk, but this is a broader section of the adult population than many people realize, including people who are overweight, have asthma or heart disease, and even people from racial and ethnic groups. that have had worse results. results of COVID-19, Dang said. Since risks increase with age, “if you're over 50, you should definitely consider Paxlovid,” she said.

“At the end of the day, having some potentially unpleasant side effects that some people report (maybe like an upset stomach or metallic taste) is much better than going to the hospital because of COVID,” he said.