In 1973, the National Hurricane Center introduced the Saffir-Simpson scale, a five-category rating system that classified hurricanes based on wind intensity.

At the bottom of the scale was Category 1, for storms with sustained winds of 74 to 95 mph. At the top was Category 5, for disasters with winds of 157 mph or more.

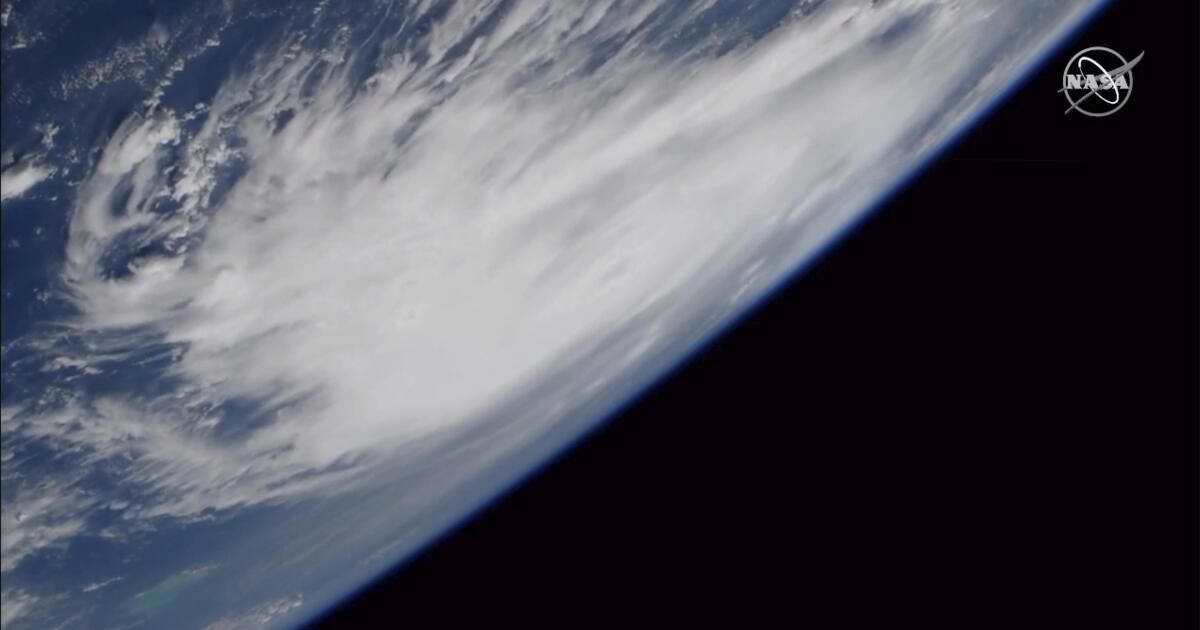

In the half century since the scale's debut, land and ocean temperatures have steadily risen as a result of greenhouse gas emissions. Hurricanes have become more intense, with stronger winds and heavier rain. This week, a University of Pennsylvania research team led by a climate scientist michael mann predicted that the North Atlantic will undergo unprecedented change 33 named tropical cyclones from June 1 to November 30.

Some scientists argue that with catastrophic storms regularly exceeding the 157 mph threshold, the Saffir-Simpson scale no longer adequately conveys the threat posed by larger hurricanes.

Earlier this year, two climate scientists published a paper which compared historical storm activity to a hypothetical version of the Saffir-Simpson scale that included a Category 6, for storms with sustained winds of 192 mph or greater.

Of the 197 Category 5 hurricanes between 1980 and 2021, five fit the description of a hypothetical Category 6 hurricane: Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, Hurricane Patricia in 2015, Typhoon Meranti in 2016, Typhoon Goni in 2020 and Typhoon Surigae in 2021. .

Patricia, which made landfall near Jalisco, Mexico, in October 2015, is the most powerful tropical cyclone ever recorded in terms of maximum sustained winds. (While the article discusses global storms, only storms in the Atlantic Ocean and northern Pacific Ocean, east of the International Date Line, are officially classified on the Saffir-Simpson scale. Other parts of the world use different classification systems).

Although the storm had weakened to a Category 4 by the time it made landfall, its sustained winds over the Pacific Ocean reached 215 mph.

“That is something incomprehensible,” he said. Michael F. Wehner, senior scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and co-author of the Category 6 paper. “That's faster than a race car on a straight line. “It is a new and dangerous world.”

In their paper, which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Wehner and co-author James P. Kossin of the University of Wisconsin-Madison did not explicitly call for the adoption of a Category 6, primarily because the scale is quickly being supplanted by other measurement tools that more accurately measure the danger of a specific storm.

“The Saffir-Simpson scale is not that good at warning the public about the imminent danger of a storm,” Wehner said.

The category scale measures only sustained wind speed, which is just one of the threats that a major storm presents. Of the 455 direct U.S. deaths due to hurricanes between 2013 and 2023 (a figure that excludes deaths from 2017's Hurricane Maria), less than 15% were caused by wind, the director of the National Hurricane Center said. , Mike Brennan, during a recent public meeting. The remainder was caused by storm surge, flooding and high tides.

The Saffir-Simpson scale is a relic of an earlier era in forecasting, Brennan said.

“Thirty years ago, that's basically all we could say about a hurricane: how strong it was now. We couldn't really tell them much about where it was going to go, how strong it was going to be, or what the hazards would be like,” Brennan said during the meeting, hosted by the American Meteorological Society. . “Now we can tell people a lot more than that.”

He confirmed that the National Hurricane Center has no plans to introduce a Category 6, mainly because it is already trying “not to emphasize the scale too much,” Brennan said. Other meteorologists said that's the right decision.

“I don't see the value in this right now,” he said. Marcos Bourassa, meteorologist at the Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies at Florida State University. “There are other issues that could be better addressed, such as the spatial extent of the storm and storm surge, which would convey more useful information [and] assist with emergency management as well as individual people’s decisions.”

As simplistic as they are, Herbert Saffir and Robert Simpson's categories are the first thing many people think of when trying to grasp the scale of a storm. In that sense, the persistence of the scale over the years helps people understand how much the climate has changed since its introduction.

“What the Saffir-Simpson scale is for is to quantify and show that the most intense storms are becoming more intense due to climate change,” Wehner said. “It's not like it used to be.”

Newsletter

Towards a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and be part of the conversation and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.