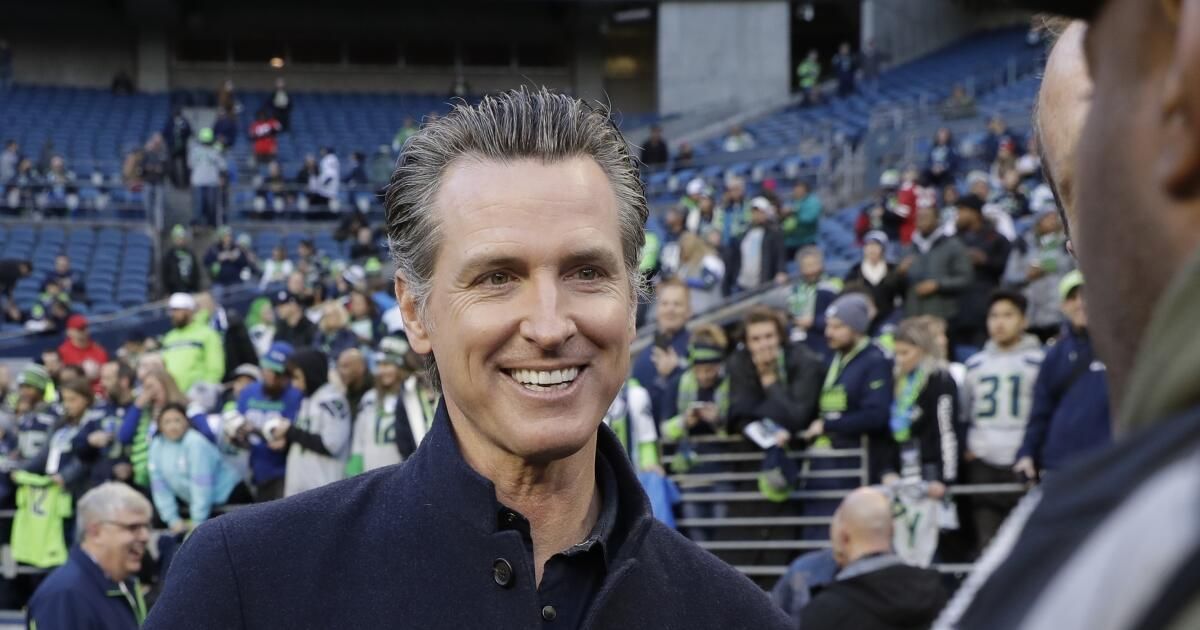

Gov. Gavin Newsom pledged Wednesday to hold the line against a bill that would ban youth football in California, saying in a statement to the Times that he would veto any such legislation.

Assembly Bill 734 was introduced last year by state Assemblyman Kevin McCarty (D-Sacramento) and cleared its first hurdle a week ago when a legislative committee voted 5-2 along party lines for the measure to be considered by the Assembly of 80 members.

Originally written to ban children under 12 from playing football, the bill was amended in committee to ban the sport for children 5 and younger starting in 2025. In 2027, the bill would raise the age prohibition for 9 years, and in 2029 it would reach 11.

California's Democratic governor, however, does not want to be part of a bill that would dictate to parents the age at which they can allow their children to participate in a sport.

“I will not sign legislation that bans youth football,” Newsom said in the statement. “I am deeply concerned for the health and safety of our young athletes, but an outright ban is not the answer.

“My administration will work with the Legislature and the bill's author to strengthen safety in youth football, while ensuring parents have the freedom to decide which sports are most appropriate for their children.”

Studies on the effects of head injuries from playing football are conflicting. A 2016 study published by the Radiological Society of North America found that a single season of American football can affect the brains of players as young as 8 years old. The researchers concluded that even hits that did not result in a diagnosed concussion produced adverse effects.

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain disease, is linked to concussions and brain trauma, but it cannot be diagnosed until the person dies and their brain can be studied. Researchers at Boston University found that among 211 football players diagnosed with CTE after their death, those who began playing football before age 12 had an earlier onset of cognitive, behavioral, and mood symptoms by an average of 13 years. years.

The researchers found that each year younger that individuals began playing football predicted an earlier onset of cognitive problems by 2.4 years and behavioral and mood problems by 2.5 years.

“Youth's exposure to repetitive head impacts in football may reduce resistance to brain diseases later in life, including, but not limited to, CTE,” said Ann McKee, director of the CTE Center at the University of California. Boston. “It makes common sense for children, whose brains are developing rapidly, not to hit their heads hundreds of times per season.”

However, a 2019 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Assn. who tracked 9- to 12-year-old football players over four seasons found that repeated hits to the head were not associated with cognitive or behavioral problems. Instead, neurocognitive performance is linked to medical diagnoses such as anxiety, depression, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

No state has banned football for children, but there have been attempts to do so. Similar bills previously introduced in California, New York, Illinois, Massachusetts and Maryland failed to pass.

McCarty's proposed law comes on the heels of the California Youth Football Act (CYFA) of 2021, which requires football coaches to complete concussion and head injury education and for parents of participating youth to receive similar information. The law also requires youth soccer leagues to help track youth sports injuries.

Opponents of the bill say it is premature and that implementing and studying the effectiveness of CYFA takes time. Newsom appeared to side with that view in his statement.

“California remains committed to building on the California Youth Soccer Act, which I signed in 2019, establishing advanced safety standards for youth soccer,” he said. “This law provides a comprehensive safety framework for young athletes, including equipment standards and restrictions on exposure to full-contact tackles.”

Football advocates along with groups advocating for less government intrusion have been vocal in their objection to the proposed law. The California Youth Football Alliance posted “Huddle up California” on Facebook, urging its members to “protect parental rights, stand up to big government and separate fact from fiction.”

In a 2023 Washington Post poll of 1,006 adults, 75% of those who identified as conservative said they would recommend youth or high school football to children, compared to just 44% of liberals. This was a change from a 2012 Post poll in which the gap between conservatives and liberals was only 70% to 63%.

McCarty said preventing kids from playing football until they reach adolescence is simply common sense.

“There are other alternatives for young kids, other sports, other football activities like flag football, that the NFL is investing a lot in,” he said. “There is a way to love football and protect our children. We have realized that there is no truly safe way to play youth football. There is no safe hit to the head for 6, 7 and 8 year olds and they should not experience hundreds of non-concussive hits to the head annually when there is an alternative.”

Still, Newsom would have veto power even if the bill passed the full Assembly and Senate, and he made clear he would use it.

“We will consult with health and sports medicine experts, coaches, parents and community members to ensure California maintains the highest standards in the country for youth soccer safety,” he said in his statement. “We owe it to the legions of California families who have embraced youth sports.”