An estimated $350 billion in Russian government assets have been frozen in Western accounts since Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered a full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. These are not idle funds. In 2023, Belgium-based financial services company Euroclear, whose settlement and clearing function means it holds €197 billion ($214 billion) in such assets, reported that they produced at least €3 billion ($3.26 billion). dollars) as interest.

Given that sanctions on the Kremlin remain in place and Putin has shown no willingness to negotiate his demand to annex a quarter of Ukraine's territory or cease his attacks, how can these assets be leveraged to push for an end to the war? or helping Ukraine resist has become a key issue for kyiv's Western allies.

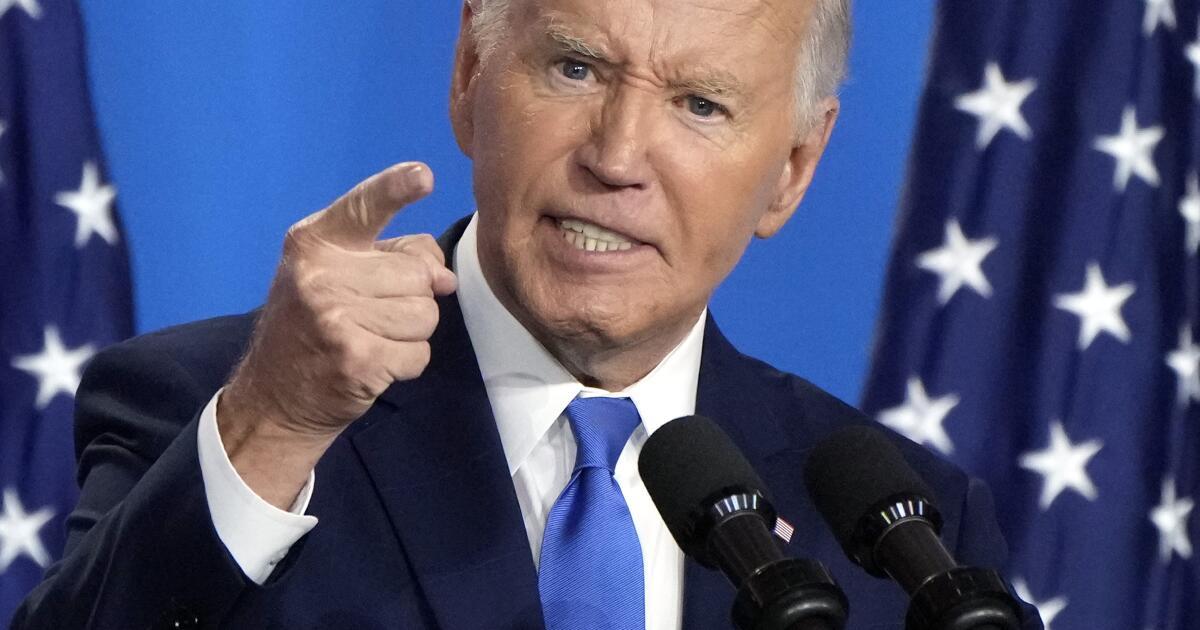

British Foreign Secretary David Cameron publicly opened the door to the idea last December, saying: “Instead of just freezing that money, let's take that money, [and] spend it on the reconstruction of Ukraine.” Washington, meanwhile, has privately circulated a plan to seize at least some of the assets, although US President Joe Biden's administration wavered on earlier European proposals for such measures in 2022.

But action speaks louder than words. The only major measure taken so far is by Belgium, which is setting aside tax revenue diverted by the frozen funds to help Kiev. However, dangerous and deadly delays resulting from the blockade by Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban and hardline Republicans in the US Congress have made the issue even more urgent.

Washington and Brussels are likely to ultimately find additional funds for kyiv, but both have already hinted that the aid will be smaller compared to what kyiv has received in the past, even as Russia's military spending grows by leaps and bounds. The Kremlin is estimated to have budgeted about $140 billion (or seven percent of Russia's gross domestic product) for its military in 2024.

And as both Europe and the United States face crucial elections in 2024, which will likely call for further reducing the cost to taxpayers of helping Ukraine, tapping Russia's frozen funds increasingly looks like not only a solution. attractive, but also necessary so that Western support for kyiv must be guaranteed in the coming years.

But the process of doing so has sparked considerable debate among international policymakers, historians, diplomats, academics and lawyers.

As with the West's initial response with sanctions to Russia's large-scale invasion, the term “unprecedented” has been thrown out quite often.

Many opponents of seizing Russia's frozen funds warn that the backlash for the West could be harsh because it would set a precedent for states to openly seize other countries' assets in response to their foreign policy decision-making. Ultimately, they fear this will lead third countries to potentially threaten the same against the West and in doing so undermine the so-called “rules-based global order.”

Others warn that it will accelerate countries' shift away from the US dollar, which is what gives US sanctions their extraterritorial reach by threatening access to the central trading instrument of global finance and commerce, a cost far greater than helping Russia. even for its allies and partners, except those subject to sanctions. This is why powers like China and India hesitate to openly help Moscow, and only fellow sanctions-affected sovereigns like North Korea, Iran and Syria do so openly.

Those calling for hesitation point to the expansion of the so-called BRICS alliance, which Putin has openly said should lead the way in finding an alternative to the dollar. But although Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are now nominal members of the bloc, the affiliated BRICS institutions remain largely ineffective.

Even the New Development Bank, which is the strongest institutional creation of the founding members of the BRICS – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – remains relatively small. It had just $26 billion in assets at the end of 2022 and has suspended making new loans to Russia.

Not only were BRICS members too divided to accept Russia's suggestion to discuss a new currency at their South Africa summit last year, but their fear of losing access to US dollars was so great that they agreed that Putin would refrain from attend the meeting.

The argument that seizing Russia's assets risks accelerating de-dollarization is a sophomoric argument. It does not take into account the fundamental flaw at the heart of a structure like the BRICS, or any other hypothetical political-economic linkage of non-Western countries.

Because the main members of the BRICS not only have disparate and often conflicting geopolitical interests – which they can sometimes set aside to ally to roll back US hegemony – but they also have substantial trade surpluses, that is, they export more than they import.

Their borrowing needs are therefore secondary to their need to find a safe haven for the profits they make from selling goods to the rest of the world, whether manufactured goods in the case of India or China or raw materials in the case of China. Russia and Brazil. Not that the US dollar and all the Washington laws and regulations that come with holding it are your ideal instrument for depositing these earnings.

But they need deficit markets like the United States, which import that capital to use their profits. And unlike their own currencies, they want currencies that lack capital controls to ensure these funds can be moved abroad. The only real alternative to the US dollar – because it also lacks capital controls and is the currency of another large deficit market – is the euro.

If the United States and Europe proceed as they should and seize Russia's funds, it may increase the desire of some other countries to move away from the dollar, but it will not erase the structural challenges to doing so.

The second reason for Western nervousness comes from the fact that they prefer to talk about operating in a “rules-based system” and paint Putin and his ilk as the biggest threat to that system. Arguments that seizing Russia's assets violates a principle of sovereign immunity or is inconsistent with international law or principles are baseless. After all, the move is a response to Russia's own violation of these principles and is only being asked to be held accountable for its action.

The idea that the international order is based on a set of rules or laws is fallacious. After all, even if there was a will, no other country would have the ability to hold Washington accountable for its 2003 invasion of Iraq and its devastating consequences. A precedent that would have raised the cost of doing so would not be a bad thing.

Consolidating the principle that unilateral aggression or annexation of territory should weaken a sovereign's standing under international law is precisely the sort of thing that a just, rules-based order should seek to implement. If the West's use of his financial power is to correct him, so be it.

Time is of the essence, as Russia has substantially increased its missile and drone attacks against Ukraine in recent weeks and Putin seeks to further deter Western support for kyiv. Confiscation of Russia's frozen assets is not only the most effective way to ensure that Ukraine can continue to resist Putin's attack, but it can also deter future such aggression by any power.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Al Jazeera.