Hanoi, Vietnam – The past fall, Vietnam opened a new expanding military museum here, and among thousands of artifacts in the four -story building and a patio full of tanks and airplanes, an exhibition quickly became the star attraction: the southern Vietnam flag.

The Government considers the yellow banner with three red stripes as a sign of resistance to the communist regime, violating the laws on inciting dissent. With few exceptions, it is not shown.

The reactions to the rare sighting soon became viral. The young visitors of the Vietnam Military History Museum published photos of themselves next to the flag with frown, thumbs down or raised medium fingers. As the photos caught unwanted attention, the flag was unleashed from a wall and folded inside a showcase. The content of social networks with rude hands gestures was eliminated from the Internet.

But the phenomenon persisted.

The flag of the former Republic of Vietnam in the Military Museum of Military History of Hanoi. The yellow three triple flag was used by southern southerds aligned by the United States during the Vietnam War, and its exhibition caused derogatory comments on social networks.

Several weeks ago, the schoolchildren who were on tour made a point to see the flag. Every few minutes, a new group crowded around the banner, also known online as the “Cali” flag, holding the middle fingers or crossing their hands to form an “x”.

In Vietnam, Cali, sometimes written as “Kali”, it has long been a reference to the Vietnamese diaspora in California, where many Vietnamese Americans still fly the southern flag to represent the fight against communism and the nation they lost with war.

However, people living in Vietnam are more likely to see it as a symbol of American imperialism, and as the nationalist feeling here has increased in recent years, evoking the state of Gold has become a kind of shorthand to criticize those opponents.

“They use it as a label against anyone who does not agree with state policy,” says Nguyen Khac Giang, a researcher at the Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, known for his political and socio -economic research on Southeast Asia.

There have been other signs of growing nationalism in the last year, often in response to the perceptions of American influence. In addition to the animosity towards the “Cali” flag, a university backed by the United States in the city of Ho Chi Minh was attacked by suspicions of foreign interference. And an aspiring Vietnamese pop star who had been a contestant in “American Idol” was saved on social networks last summer after images of his song in the commemorative service of the United States of an anti -communist activist arose.

Vietnamese nationalism, said Giang, is reinforced at all levels by the country's unique government.

School groups visit the newly opened Military Museum of Vietnam de Hanoi. The museum contains exhibitions, photographs, maps and scale models on armed resistance over time, from the armed struggle for the independence of France to the armament used during the Vietnam War.

The Government controls education and public media; The independent journalists and bloggers who have criticized the government have been imprisoned. In addition, the ability of the party to influence the narratives of social networks has improved in recent years, particularly among the youth of the nation.

Since 2017, the Vietnamese authorities have employed thousands of cyber troops to the online police content, forming a military unit under the Ministry of Defense known as Force 47. In 2018, the country approved a cyber security law that allowed it to demand social media platforms to demolish any content it deems anti-state. The resulting unilateral discourse means that opinions that are not aligned with official propaganda often attract harassment and ostracism.

Sometimes, the government has also used that power to try to control nationalism when it becomes too extreme, although banning positions on the southern Vietnam flag did little to quell enthusiasm in the museum.

Some visitors who were making manual signs said they were expressing their disapproval of a regime that, who had been taught, oppressed to the Vietnamese people. A teenager displayed and sustained the national flag, red with a yellow star, for a photo.

“It's hard to say if I agree or disagree with rude gestures,” said Dang Thi Bich Hanh, a 25 -year -old cafeteria manager who was among visitors. “The gestures of these young people were not quite well, but I think they reflect their feelings when looking at the flag and thinking about that part of history and what the previous generations had to endure.”

A bust of Ho Chi Minh in Thanh Van School in the province of Bol Kan, Northern Vietnam. Each public office and public schools in Vietnam contains a photo or figure of Ho Chi Minh, a venerated historical figure that has become a nationalist symbol in the country.

Before leaving, a selfie was taken with the middle finger high to the folded fabric.

:::

Five years ago, when a student from a rural region of the Mekong Delta obtained a complete scholarship for an international university in the city of Ho Chi Minh, it seemed a dream come true. But last August, when the school was trapped in the growing wave of nationalism, he began to worry that his association with the Fulbright Vietnam University could affect his safety and his future.

“He was afraid,” said the recent graduate, who requested anonymity for fear of compensation. He had just started a new work in education and avoided mentioning his alma mater to co -workers and when wearing shirts marked with the name of the school.

“You had all kinds of stories. Especially with the dissinformation that extends at that time, it had some negative impacts on my mental health.”

The attacks included accusations that Fulbright, which opened in 2016 with partial funds from the United States government, was cultivating western liberal and democratic values that could undermine the Vietnamese government.

The nationalists criticized any possible indication of anti -communist inclinations in school, such as not prominently showing the Vietnamese flag at the beginning. Even the graduation slogan last year, “intrepid”, caused suspicions that students could be planning a political movement.

“You are seeing new heights of nationalism safely, and it is difficult to measure,” said Vu Minh Hoang, diplomatic historian and professor of the University.

Crowds in the military parade of April 30 in the city of Ho Chi Minh marking the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War.

Hoang said that the accusations online, none of which were true, led to threats of violence against the university, and there was talk that some parents withdraw their children for them. Several students said their affiliation delivered the hate speech of strangers and distrustful questions of relatives and employers.

The academics said that the Vietnamese government probably acted quickly to close the reaction against Fulbright to prevent anti -American feeling from damaging its ties with the United States, its largest commercial partner. But some of the original accusations were spread by state media and the bots associated with the Ministry of Defense, hinting at a schism within the party.

Hoang said that although nationalism is often used as a force of union in Vietnam and beyond, it also has the potential to create instability if it grows beyond the estimation or control of the government. “For a long time, it has been the official policy to make peace with the Vietnamese community abroad and the United States,” said Hoang. “Therefore, this wave of online ultranationalism is seen by the Vietnamese state as useless, inaccurate and, to some extent, against official addresses.”

:::

Last summer, the images of Myra Tran singing at the Ly Tong Westminster Funeral, an anti -communist activist, emerged online. He had achieved a degree of fame by winning a Canto reality show in Vietnam and appearing in “American Idol” in 2019, but received a tough condemnation of online nationalists and state media when the video of several years ago went viral.

Facebook and Tiktok users talked Tran, now 25 years old, as a traitor, anti-vietnam, and Cali.

The controversy caused a broader movement to discover other Vietnamese celebrities suspected of conspiring against the country. Internet detectives toured the web for anyone who, like Tran, would have appeared next to the Southern Vietnam flag and attacked them.

A entertainment writer in the city of Ho Chi Minh, who did not want to be identified for fear of being attacked, says that as young Vietnamese have become more nationalists online, musicians and other artists have felt pressure to actively demonstrate their patriotism or risk the anger of cancellation culture.

He added that the scrutiny of symbols such as the South Vietnam flag has given those with connections with the United States, a more important reason to worry about being attacked online or losing job opportunities. That could discourage the Vietnamese living abroad, a demographic group that the government has tried to attract the country for a long time, to pursue businesses or careers in Vietnam.

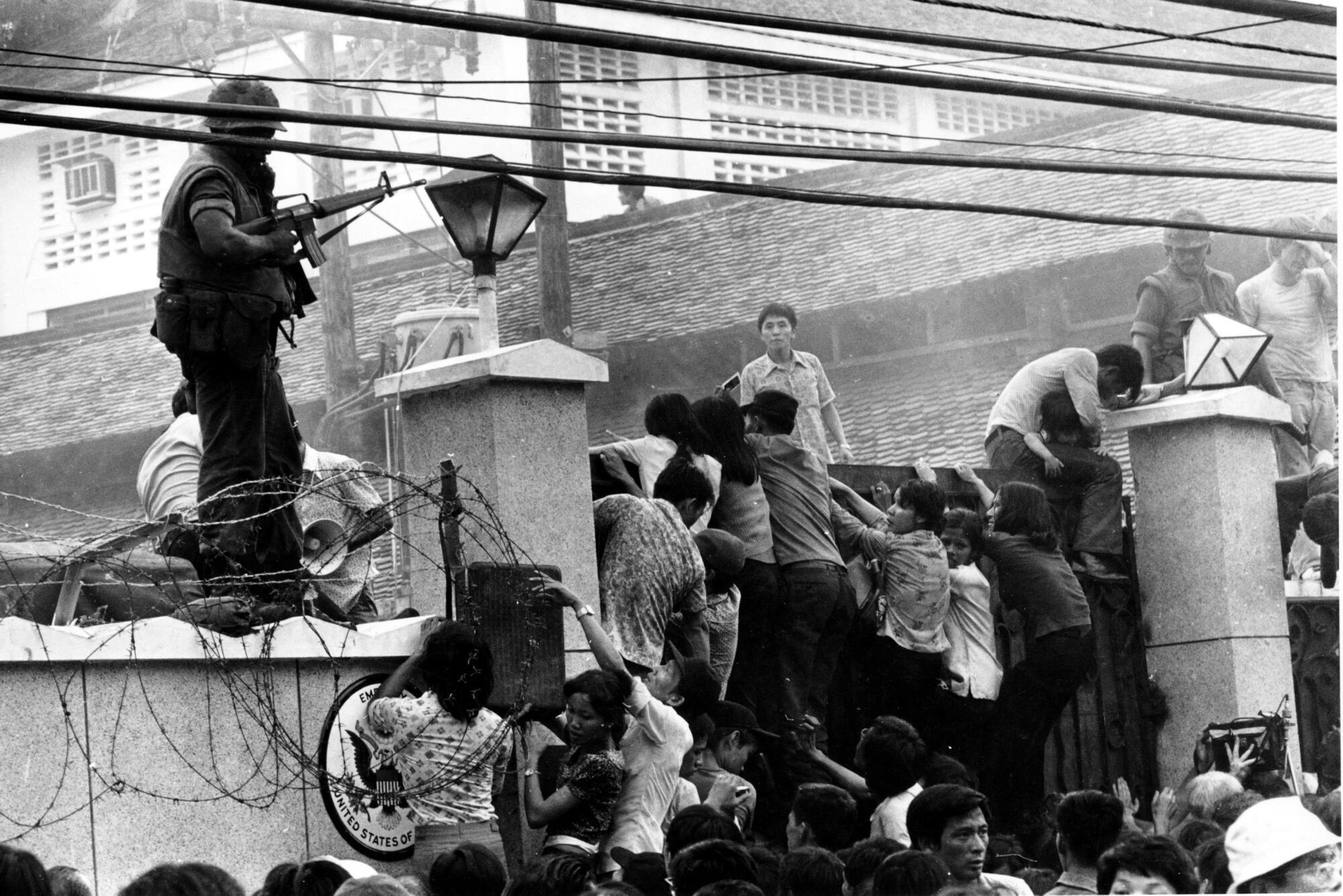

The mobs of the Vietnamese people climb the wall of the United States Embassy in Saigon, now the city of Ho Chi Minh, trying to reach a helicopter collection zone just before the end of the Vietnam War on April 29, 1975.

(Neal Ulevich / Associated Press)

“There was a time when artists were very cold and careless, although they know that there has been this rivalry and this story,” he said. “I think everyone is becoming more sensitive now. Everyone is nervous and tries to be more careful.”

Tran was intimidated online and cut from a musical television program for its “transgression.” He issued a public apology in which he expressed his gratitude to be Vietnamese, denied any intention to damage national security and promised to learn from his mistakes.

Two months later, Tran was allowed to act again. He returned to the stage in a concert in the city of Ho Chi Minh, where he cried and thanked fans for forgiving her.

But not everyone was willing to apologize. From the crowd, several spectators made fun and shouted for Tran to “go home.” The concert videos caused a fierce debate on Facebook among the defenders of Tran and his critics.

“The patriotic young people are so chaotic now,” complained a Vietnamese user after denouncing the hatred that Tran was receiving online.

Another return shot: “Then return to Cali.”