About 600 times a day, the esophagus carries what's in your mouth to your stomach. Usually it's a one-way route, but sometimes acid leaks out of your stomach and comes back up. That can damage the cells lining your esophagus, causing them to grow back with genetic errors.

About 22,370 times a year in the United States, those mistakes result in cancer.

Esophageal cancer can be cured if it is detected and treated before it spreads deeply or to other organs, but that is often not the case.

“The way this usually happens is a patient has had reflux symptoms for many years, has taken Tums or something, and suddenly has difficulty swallowing, so they go to the emergency room,” she said. Dr. Allon Kahngastroenterologist and associate professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Arizona. That's when doctors discover a tumor that has grown inside the walls of the esophagus and possibly beyond.

“At that point,” Kahn said, “it’s incurable.”

That's why only about 20 percent of Americans with esophageal cancer are still alive five years after diagnosis. To improve that number, doctors say they don't necessarily need better drugs, but better ways to detect the cancer while it's still in its earliest, highly treatable stages.

And to achieve this, they need a breakthrough in disease detection.

“The concept of detection is to find dangerous things before they do dangerous things,” he said. Dr. Daniel Boffachief of thoracic surgery at Yale.

It works in diseases such as breast cancer, lung cancer, and colon cancer. In these cases, there is a clear progression of steps that lead to cancer, and only cancer.

But that doesn't seem to be the case with esophageal cancer.

“We don't really know who to screen, how often to screen and what we can see that will tell us, 'This person is going to develop a dangerous cancer,'” Boffa said.

He compared the situation to the difficulty of forecasting a tornado.

“Most tornadoes occur when conditions are favorable for a tornado,” he said. “But most of the time, when conditions are favorable for a tornado, there is no tornado. And many times, tornadoes occur outside of those conditions.”

Another complicating factor is that esophageal cancer cases are rare, accounting for about 1% of all cancers diagnosed in the U.S.

Imagine the 100,000 college football fans gathered at Michigan Stadium in Ann Arbor on a game day, he said. Dr. Joel Rubensteina research scientist based three miles away at the Lt. Col. Charles S. Kettles Veterans Affairs Medical Center and a gastroenterologist at the University of Michigan. Imagine then having to figure out which of those four fans will develop esophageal cancer this year.

Detecting esophageal cancer is not a trivial procedure.

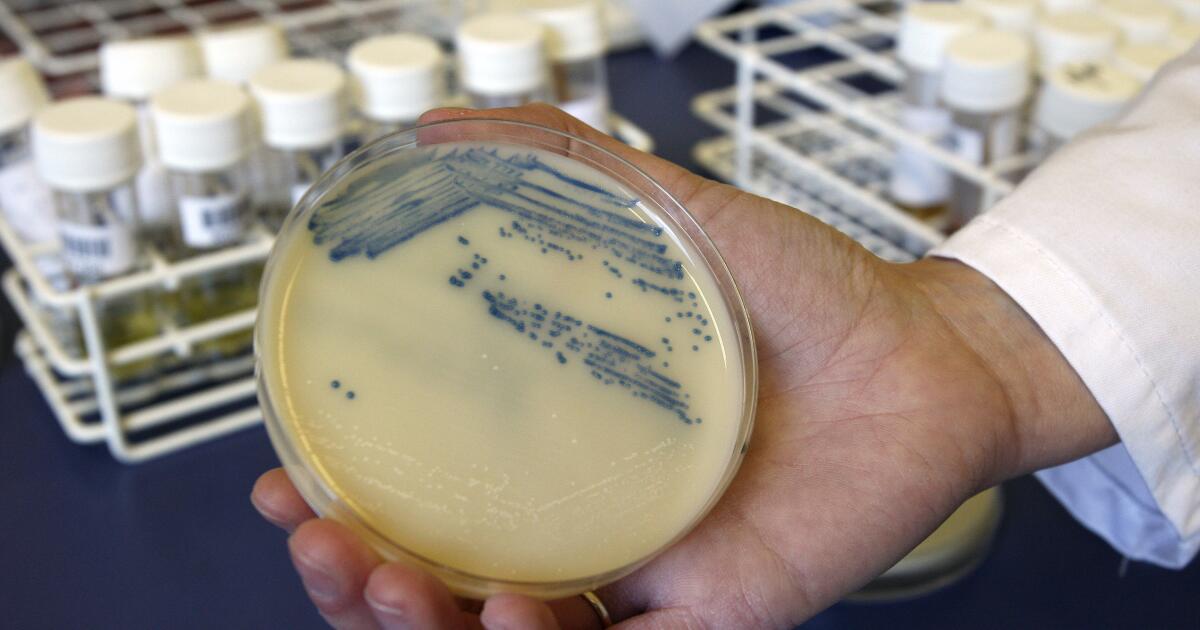

The standard method involves inserting an endoscope (a flexible tube with a camera on the end) down the patient's throat and passing it into the stomach. The camera allows doctors to closely inspect the esophagus and check for abnormal cells that could become cancerous.

A probe protrudes from the instrument channel of an endoscope used to diagnose esophageal cancer.

(Cover images via AP Images)

The tube also serves as a conduit for tools that collect tissue samples, which can be sent to a pathology lab for diagnostic analysis. If a doctor sees a tumor that looks like early-stage cancer, he or she can remove it on the spot.

It sounds simple, but patients must be sedated for the procedure, which means they miss a day of work. Endoscopy is also expensive, and there is a shortage of doctors who can perform it.

“We only detect 7% of cancers through endoscopy,” Kahn said. “We need to find a way to increase that number.”

In the U.S., the most common form of cancer begins at the base of the esophagus. The cells in that area aren't designed to withstand exposure to stomach acid, so in people with chronic acid reflux, they sometimes adapt and become more like intestinal tissue. That condition is called Barrett's esophagus, and about 5 percent of American adults have it.

“If that was all there was to it, we would say, ‘That’s great,’” Kahn said. “But unfortunately, when you have that change in cell type, there are genetic changes that predispose the patient to cancer.”

According to Dr. Sachin Wani, a gastroenterologist and professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, about 0.3% of people with Barrett's esophagus develop esophageal cancer each year. And compared to people without Barrett's esophagus, they are about nine times more likely to die from esophageal cancer.

This means that screening for Barrett's syndrome is equivalent to screening for esophageal cancer.

Doctors largely agree on a core set of risk factors, including chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease, smoking and excess weight around the abdomen. Other risk factors include being at least 50 years old, being male, being white and having a family history of Barrett's or esophageal cancer.

There is less consensus about how many risk factors a person must have to warrant screening.

According to recommendations from the American College of Gastroenterology, more than 31 million people are eligible for screening. The American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines put that number at 52 million, and the American Gastroenterological Association recommendation extends it to 120 million, said Dr. Gary Falk, a gastroenterologist and professor emeritus of medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

All of these recommendations leave room for improvement. Only 50% to 60% of people who qualify for screening actually have Barrett's esophagus, said Dr. Prasad Iyer, director of gastroenterology at the Mayo Clinic in Arizona.

“The selection criteria are not precise enough,” he said.

In fact, at least 90% of people who have risk factors for Barrett's esophagus don't actually have the disease, Iyer said. That includes the vast majority of people with acid reflux.

That's why doctors are turning to artificial intelligence to identify additional features that may improve their ability to identify those most likely to develop esophageal cancer and Barrett's disease.

“Everyone in the medical field is interested in AI,” Falk said. “We think it’s going to revolutionize things.”

Iyer and his colleagues are developing an artificial intelligence tool that examines the electronic medical records of Mayo Clinic patients to find those who should be screened for Barrett’s esophagus. The tool considers more than 7,500 different data points, including past medical procedures, lab test results, prescriptions and more. (Among the surprises: A patient’s triglycerides and electrolytes had predictive value.)

“This is probably something a human couldn’t do efficiently,” Iyer said.

In testing, the overall accuracy of both tools was 84%. While these are substantial improvements, the team would like to increase that to 90% before deploying them in the clinic, Iyer said.

Rubenstein and his colleagues in Michigan created something similar, using machine learning techniques to analyze the medical records of Department of Veterans Affairs patients across the country. Their tool also performed better than official guidelines from medical societies, with 77% accuracy. Now the team is working to refine their detection threshold by adding cost-benefit into the mix.

Once in use, tools like these could ease the burden on overburdened primary care physicians, who aren't necessarily up to date on the latest screening guidelines and refer less than half of their eligible patients for testing.

“You’re going to flag the patient and say, ‘This patient should be screened,’ or ‘This patient should not be screened,’” Iyer said. “That’s what the future really needs.”