Huajóbar de Guadalupe, Mexico – The courtship opened through a dirt road, passed well equipped houses that provide a contrast to the rock covered in rocks that leads to the top of the top of the hill.

This community in the Mexican central state of Michoacán houses about 1,500 people, many of whom make life planting corn, plums, peaches and other crops that cut symmetrical rows through the green slopes, now shining a emerald green, the generosity of recent rains.

But the sterling brick residences and conflict along Rocky Road are the legacy of a generation of immigrants, men like Jaime Alanis García, who went to work in the fields, factories and other workplaces of California, sending the money back to his village to build homes and other projects.

Among the works financed through immigrant remittances is the Chapel of Our Lady of Guadalupe, where a funeral mass was held on Saturday, for Alanis García.

It is the first known mortality linked to the fulfillment of the Trump administration work site, in this case, a couple of sweeps on July 10 through cannabis facilities of Glass House Farms in California.

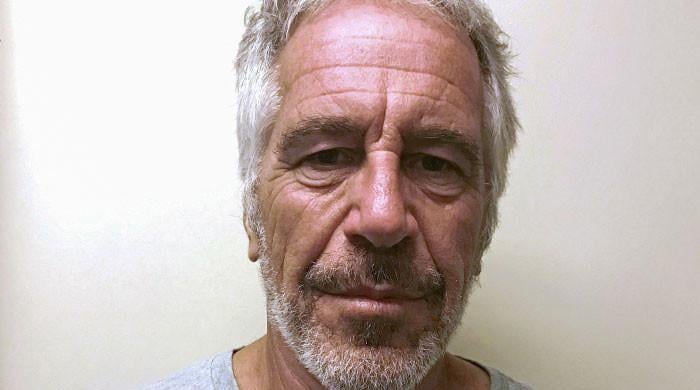

Guadalupe Huajóbar residents said final of Jaime Alanis García, who was fatally injured when he climbed on a greenhouse and fell 30 feet while fleeing immigration agents in Camarillo.

(Juan Jose Estrada Serafin / for the times)

Alanis García, 56, was fatally injured when he fell at 30 feet from a greenhouse while fleeing immigration agents at the glass house in Camarillo, relatives say. Mexican consular officials fixed so that his body was sent from California.

“It was like many of us, a working person who went to California to make a living, to help his family,” said Rosa María Zamora, 70, a native of Huajóbar de Guadalupe, who was visiting from home in Houston. “For us, California represented an opportunity, an opportunity to improve our horizons.”

A quarter of a century ago, Zamora said, he left to join her husband, a field worker in California. Later, the couple found a job in Mataderos in Nebraska, where he suffered a serious leg in the leg for a cutting blade.

“It's so sad that Mr. Jaime will return in this way,” Zamora said.

He was among about 200 mourners who accompanied Alanis García on his kind final trip through his hometown.

“Look how many people are here today,” said Manuel Durán, a brother -in -law of Alanis García. He traveled here with other relatives of Oxnard, where Alanis García lived. “It was very loved.”

Durán put on a t -shirt stamped on the front with stylized Ángel wings that rise from a photo of Alanis García. “In love memory,” the text read.

The back of the shirt presented the hashtag #Justiceforjaime, in English and Spanish, which reflects the statement of relatives that the July 10 operation was reckless. “We want justice, please,” said Janet Alanis, 32, his daughter. “Tell everyone that everything we ask for is justice.”

The United States National Security Department defended the raid, which according to the authorities resulted in arrests of more 300 people. The authorities say that the agents asked for medical assistance from Alanis García, who, according to an autopsy, suffered head and neck injuries.

The residents of Huajúmba de Guadalupe meet for the funeral of Jaime Alanis García, whom many had not seen since he was a teenager.

(Juan Jose Estrada Serafin / for the times)

Alanis García left Huajóbaro from Guadalupe when he was young but, according to relatives and acquaintances, he always provided his wife and daughter, who remained here, depending on his profits as an agricultural worker. He visited his hometown 17 years ago, for his daughter's QuinceañeraOr celebration of the 15th birthday, residents said.

Such prolonged separations have become increasingly the norm in the decades since Alanis García crossed for the first time as an undocumented worker in California. The stretching of the border between the United States and Mexico that once presented fences and minimal police have now become strongly militarized. For many undocumented immigrants, that has eliminated Once Routina's trips face home to visit their loved ones in Mexico.

The news of the immigration rates of the United States has returned to immigrant communities throughout Mexico, which increases deep anxieties.

“My husband lives in Oxnard, but, thank God, he did not work in the place where the raid was,” said Margarita Cruz, 47, a mother of three children who attended the funeral. “My husband tells me that the situation there is very difficult. There is a lot of fear that people can be arrested.”

Her husband started 15 years ago for California, Cruz said. The last time he visited four years ago.

“Here we survive thanks to the money that our husbands and children send back to the United States,” Cruz said. “Now, everyone is concerned that they deport our relatives. What will we do? There is no job here. Look what happened to Mr. Jaime.”

Somehow, things have worsened in many rural sections of Mexico that have sent immigrants to the north. The dramatic ascent of Mexican organized crime has thrown a shadow on much of the state of Michoacán, where rival gangs fight for the control of drug capture, extortion and other rackets.

On Friday, shortly after the highly anticipated arrival of the body of Alanis García de California, a state police officer who accompanied the remains was clearly agitated. He was anxious to leave, and warned the visiting journalists to hit him outside the city to the sunset.

“Do not get caught here after dusk,” said the nervous policeman, who soft an assault rifle while scanning the surroundings. “It's very, very dangerous here. Two groups are fighting for control.”

The members of the community said goodbye to Jaime Alanis García in their hometown in the Mexican state of Michoacán.

(Juan Jose Estrada Serafin / for the times)

But it was Pacific Saturday, since the relatives accompanied Alanis García's body to the church, where the coffin was flanked by candles. The elaborate floral arrangements adorned the banks and the walls. A band of 12 pieces of brass instruments, wood and percussion wind provided a musical backdrop in the church courtyard. Musicians wore white jackets and flower prints and black shirts while playing funeral melodies.

After the Mass, the men of the city loaded the wooden coffin in the hill at approximately half a mile to the cemetery. The band was still playing while stick carriers walked forward. Many in the procession raised umbrellas against a midday sun.

The coffin, adorned with flowers, opened in a pavilion in the cemetery. A relative placed a crucifix in the chest of Alanis García. His photo looked from inside the coffin. The mourners approached a last look at a man that many had not seen since he was a teenager.

The mourners gathered when the rosary prayed. Those who pray asked the Virgin Mary, “Queen of Migrants”, to pray for the soul of the deceased.

The coffin was closed and the men lowered him to the adjacent grave. The mourners threw individual roses into the last resting place of Alanis García. The men turned to peel on the reddish earth.

Family members say that Alanis García, like so many immigrants, always wanted to return to his family.

His anguished widow, Leticia Cruz Vázquez, cried: “I didn't want it that way!” Before fainting. Relatives and neighbors brought their loose figure of the crowd.

McDonnell is a writer of the Times and Sánchez staff, a special correspondent. The special correspondent Liliana Nieto del Río contributed to this report.