What happened to the empathetic Joe Biden who won the 2020 presidential election?

Some days it seems as if that kind Uncle Joe has been replaced by a cranky old politician, upset with voters who don't give him credit for a strong economy.

Last week, when the Labor Department reported that inflation had risen to 3.5%, likely delaying an interest rate cut, Biden did not offer much comfort.

“We have drastically reduced inflation from 9%,” he said. “We are better placed than when we took office.” That's true, but it's no consolation to consumers and homebuyers.

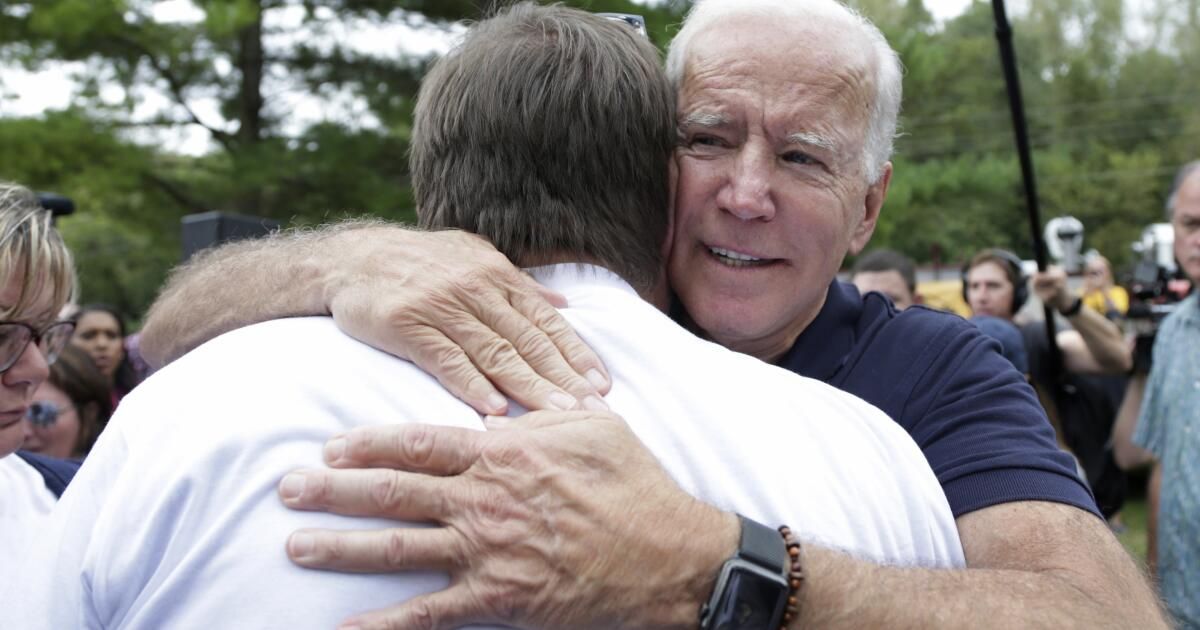

Joe Biden puts his arm around his supporter Diana Feige after speaking during an event in Keene, NH, during the 2020 presidential campaign.

(Michael Dwyer/Associated Press)

A week earlier, when a reporter asked Biden what he would say to Americans stressed by high prices, the president responded: “I would say we have the best economy in the world. We have to improve it.”

It is a topic that has been playing for months. In his State of the Union address, he praised the American economy as “the envy of the world.”

But a chorus of Democratic strategists say it's the wrong message, mainly because it lacks the element that was once Biden's political superpower: empathy.

“You can't tell people they're better off than they think,” said Mark Mellman, a veteran political consultant. “It is important to recognize his pain. Otherwise, it seems like a sign that you don't understand their lives.”

“I wouldn't go out and praise the miracle of Biden's economy,” said David Axelrod, who helped Barack Obama win two presidential elections.

“The right strategy is to say, 'Look, we've made a lot of progress… [but] The way people experience this economy is the same way I did when I grew up in Scranton, Pennsylvania,'” Axelrod said in an interview with conservative pundit Bill Kristol. “How much did you pay for the food? How can I pay for gas and rent? These are still a problem and I am fighting that fight.'”

“The message has to start with empathy and focus on prices, which is the issue that matters most to voters,” said Stanley Greenberg, who helped Bill Clinton win the presidency in 1992. Otherwise, he said, “people “he gets angrier and angrier.” .”

During the 2020 campaign, as Americans were reeling from the human and economic costs of the COVID-19 pandemic, Biden often spoke of his personal story: his upbringing in a family of modest means, the death of his first wife and her young daughter in a 1972 highway accident, the death of her son Beau in 2015, and her feeling of kinship with others who suffered loss.

Biden's campaign was not shy about drawing attention to the contrast with then-President Trump, who seemed more intent on downplaying the impact of the pandemic. “Empathy is on the ballot,” Jill Biden, soon to be first lady, said on Twitter. But those moments of empathy appear to have become less frequent since Biden took office.

Biden acknowledges that the economy still struggles, but not as often as he emphasizes that his policies are succeeding.

“We have more to do. I get it,” she said in Arizona last month. “But there's no question, our plan to deliver for the American people is working right now.”

It's also true that the economy has been improving over the past two years, with strong growth, job creation and, in recent months, wage increases. When Biden took office in 2021, the economy had begun to recover from the pandemic, but unemployment was still above 6%. Since then, more than 15 million jobs have been created and the unemployment rate has remained below 4% for more than two years.

But Biden has reaped few political benefits from those positive trends, mainly because inflation, which peaked at 9% in 2022, has led to persistently high mortgage prices and rates.

Voters are in a bad mood. An Economist/YouGov poll released last week found that 67% of Americans believe the country is “on the wrong track” and 39% believe the economy is in recession. (It's not.) Only 20% say they think the economy will improve if Biden is re-elected. Twice as many, 44%, said they believe the economy will improve if Trump wins.

The president still gets some credit for his empathy, but less than before. In 2020, the Quinnipiac poll reported that 61% of voters said they believed Biden “cares about the average American”; This year, the same survey found the number had dropped to 51%. (Trump trailed with 42% on the issue in both 2020 and this year.)

Inflation is a frustrating problem for any president. There is little he can do to reduce grocery or gasoline prices. A president is not supposed to pressure the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates, and he probably wouldn't succeed if he tried.

So Biden has tried to show voters that he is doing the best he can, working to lower prices in areas where the federal government has influence. One of her favorite talking points is her sponsorship of the 2022 law that allows Medicare to negotiate drug prices and caps the monthly cost of insulin at $35; Biden says he will try to expand the law's reach if he is re-elected.

But critical strategists say there is more it can do, especially if it can revive its superpower.

“I think he can win with a message that starts with empathy, saying 'I know high prices are killing people,' and goes on to talk about higher taxes on billionaires and corporations,” Greenberg said. “Let Joe be Joe.”

“Bottom line: Be more like Joe from Scranton and less like President Biden from Washington,” Axelrod said.

Biden's advisers say, sometimes in unprintable language, that they don't need as much free advice. Politico reported last year that the president called Axelrod “a jerk.”

And yet, they may be listening.

This week, Biden will launch a three-day “economic tour” of Pennsylvania and will begin by talking about taxes. His first stop: Scranton.