The donkeys are angry. Exhausted, out of work, and victims of decades-long systemic abuse, they have decided it is time to protest.

The donkeys, metaphorically, are us.

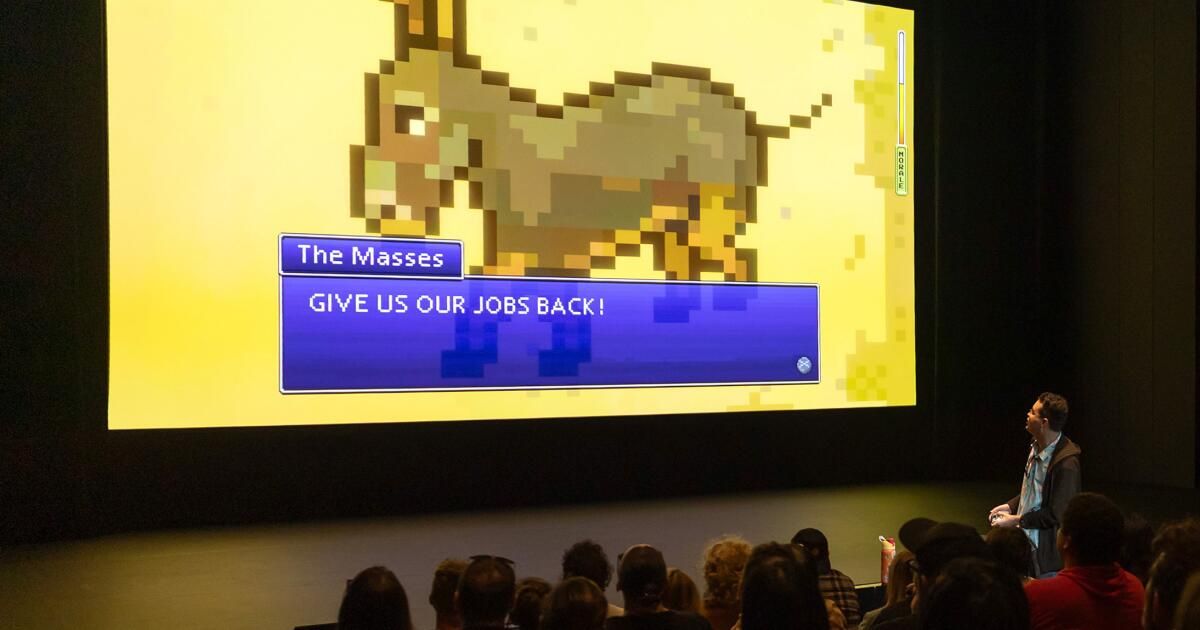

At least that's the premise of “asses.masses,” a video game played by and for a live audience. It is theater for the post-Twitch era, performance art for those who have been weaned on “The Legend of Zelda” or “Pokémon.” Most importantly, it is entertainment as political dissidence in these divisive times. Although the project dates back to 2018, it is difficult not to include the year 2026 in its narrative. Whether it's wrongful incarceration, mass layoffs, or issues centered around the automation of jobs by technology, asses.masses, although they typically last more than seven hours (yes, more than seven hours), are urgent work.

The audience applauds several decisions made during the performance of “asses.masses” at UCLA's Nimoy Theater.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

And for the audience at Saturday's performance at UCLA's Nimoy Theatre, it felt like a call to arms. Citizens executed in the street for exercising their right to freedom of expression? That's here. Clashes with authorities that recall images seen in several American cities in recent months? Also here, although in a retro pixel art style that may recall the “Final Fantasy” series from its days on Super Nintendo.

In a city that has been devastated by fires, ICE raids and a series of layoffs in the entertainment industry, the crowd of nearly 300 people was angry. Chants of “ass power!” – the donkey protest slogan – were heard throughout the day as attendees politely gathered near a single video game controller on a stage to play, becoming not only the avatar of the donkeys but a momentary leader of the collective. Applause would erupt when a young donkey concluded that “I think the system is rigged against everyone.” And when technological advances, clearly a substitute for artificial intelligence, were described as “evil, heartless machines that take away jobs and kill children,” there was knowing applause, as if no exaggeration was being said.

“Our theater is supposed to be a rehearsal of life,” says Patrick Blenkarn, who co-created the play with Milton Lim, interdisciplinary artists from Canada who often work with interactive media.

“We grew up in a radical political tradition of theater,” says Patrick Blenkarn, right, who co-created “asses.masses” with Milton Lim.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

“We grew up in a radical political tradition of theater, which is where we can rehearse emotional experience: catharsis,” Blenkarn says. “That's what art is supposed to do. We've been very interested in the idea that if we come together, what are we going to do and how are we going to do it? What we're seeing in your country and in other countries is the question of how are we going to change our behavior, and will the people who currently have the controller listen? And if they don't, what will we do?”

Video games are inherently theatrical. Even if one plays alone on the couch, a video game is a dialogue, a performance between a player and invisible designers. Blenkarn and Lim also spoke in a pre-show interview about their desire to recreate the feeling of gathering around a TV and passing a controller between family or friends while offering feedback on someone's gaming style. Just to scale. And while I thought “asses.masses” could also work as a solitary experience at home, its themes of collective action and reaching group consensus, often through boos or shouts of encouragement, made it particularly well-suited for a performance.

UCLA’s Nimoy Theater hosted “asses.masses” this weekend.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Beginning at 1 p.m. and ending shortly after 8 p.m., coincidentally, Blenkarn says, for about one work day, not everyone came to the conclusion of “asses.masses.” About a quarter of the audience (a crowd that was clearly familiar with the multiple video game style represented in “asses.masses”) couldn't withstand the endurance test. But in an age of binge-watching, I didn't find the length prohibitive. There were multiple intermissions, but they also became part of the show since there was no set time limit. Blenkarn and Lim asked the audience, through a message on the screen, to jointly agree on a duration, emphasizing, once again, the importance of collective cooperation.

And “asses.masses” is interesting because, in part, it embraces the animated absurdity and inherent experimentation of the medium. Although it often had a retro pixel art style, sometimes the game would shift to a more modern open world look. And the story detours along multiple paths and side quests, some requiring wild coordination, like a rhythm game meant to simulate sex with donkeys, and others more tense, like “Metal Gear”-style sneaking around, with the donkeys hidden in cardboard boxes.

The public votes, often applauding or booing, on the “ass.mass” options.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

The way “asses.masses” changed tone and tenor was reminiscent of a game like “Kentucky Route Zero,” another serialized, alternately realistic and fantasy game with political overtones. At other times, such as in the surreal world of the donkey's afterlife, I thought about the colorful and unpredictable universe of the music-centered game “The Artful Escape,” a quest for personal identity and self-realization. The donkeys of “asses.masses” form an ensemble and often try to lead the audience in different directions. As much as some push for protest as a form of community healing and progressive action, others take a cynical attitude and consider that path to be “intellectually compromised” by a “commitment to the ideals of the past.”

The goal, Lim says, is to create a kind of game within a game, one that is played with a controller and is about debate among a crowd. “It's not about having a billion endings,” says Lim. “We understand that it's a theater show and we, as writers, have goals about where we want it to go. But the decisions that people make in the room really matter. The play takes place half in the room and half on the screen.”

The public, for example, can help keep certain donkeys alive. Or what jobs a group of renegade donkeys can choose. Our audience voted to let donkeys into the circus, at least until they were deemed obsolete and sent to detention centers, which felt uncomfortable at the time. Such topicality is what attracted CAP UCLA leader Edgar Miramontes to the program, despite his admission that he was largely unfamiliar with the world of video games.

“It doesn't shy away from the nuances of when organizing happens and what we're seeing in our world right now,” Miramontes says. “There are cases where a donkey can die because, as you organize to achieve your goals, these things happen. We've seen this in our Civil Rights Movement and other movements and the current movement that's happening right now around ICE.”

The Nimoy event, part of the UCLA Center for Performance Art’s current season, was the fiftieth time “asses.masses” was presented. The show will continue to tour, with a performance in Boston scheduled for next weekend, and will arrive in Chicago later this year. Our Saturday donkeys didn't solve all of the world's inequalities, but they lived full lives, attending raves, having casual sex, and even playing video games.

A player celebrates during “asses.masses,” a live-action theatrical video game.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

The program is an argument that progress is not always linear, but community is constant. As one of the donkeys says at one point: “If you're not doing something that makes you happy, do something different.”

“In case someone says, 'I don't want to be lectured,' or I don't want to do all this work, it feels like you're just having fun with friends,” Lim says. “Perhaps revolution does not always seem simply this. Maybe it's this too.”

And like many video games, maybe it's an opportunity to live out some fantasies. “We beat up the riot cops in the game,” says Blenkarn, “in case anyone was waiting for that opportunity.”