Homer wrote about the Trojan War; Alfred Lord Tennyson, the Crimean War; Walt Whitman, the civil war; Wilfred Owen, First World War. His poems are part of world history and culture. Poets must and must document the destruction and horrors of war.

But can poetry improve a war or accelerate a peaceful resolution? Perhaps, but only if poets and readers can slip behind the enemy lines, or if the poetry of the “enemy” can cross those lines. The last war in the Middle East, and the repercussions here, have illustrated the power and difficulty of reading the verse on the other side.

At the risk of being accused of naivety, I believe, I affirm that poetry can be a vehicle for change and peace in the midst of war and other conflicts. Robert Bly and Denise Leverov influenced social consciousness about the Vietnam War. More recently, a rebirth of marginalized voices promoted a more general consciousness of systemic racism in the United States.

No lynching story is more vivid than the “Jasper Texas 1998″ by Lucille Clifton, about the murder of James Byrd Jr. and all the stories of the murders that caused the movement of Black Lives Matter, deeply I remember Ross Gay ” Small Needful Fulful made “about the murder of Eric Garner in New York.

In the conflict between Israel and Hamas in Gaza, Palestinian voices must be heard if lasting peace is going to be achieved. Among those who have moved me deeply are the poets Mosab Abu toha and Fady Joudah. They have brought me to Gaza the way I could not cover television news.

I invite any Jewish or Israeli poet who has not deepened in contemporary Palestinian poetry to take a step behind enemy lines to read these and other poets. Reading them means experiencing not only the anguish and horrors of war, but also finding all the strength of the wrath of another. And beyond anger it is a human not different from oneself.

“The well of my grandfather” of Abu toha contrasts an image of the poet “raising cubes of water / of the camp of the camp” with that of his grandfather, whose “hands pour water / down into the well” in Yaffa, where he is still : “He never left it, even after Nakba, / even after death.” It connects the Palestinian poet with this American Jewish poet, as grandchildren whose grandparents' lives continue to hold them. Such moments of empathy, in my opinion, move mountains.

How strange, then have read that thousands of writers and members of the entertainment industry had signed a letter committed to boycoting Israeli cultural institutions, those who could bring them back his The lines of the enemies to show them something that have been closed to know. It seems to me that these writers and artists commit themselves No Knowing, a No Let art do what only art can.

A Opinion article Published in the New York Times last year, the header “A Chill has fallen over the Jews in the publication,” he referred to an online spreadsheet of the supposedly “Zionist” authors aimed at being on the blacklist. It is read as the recent book of prohibitions aimed at gay and trans literature, the era of revisited McCarthy, or even the bonfires that consumed “decadent” books in Nazi Germany. Why are Blacklisters afraid of taking a step behind enemy lines, the lines they draw to separate from Israeli and American Jewish experience?

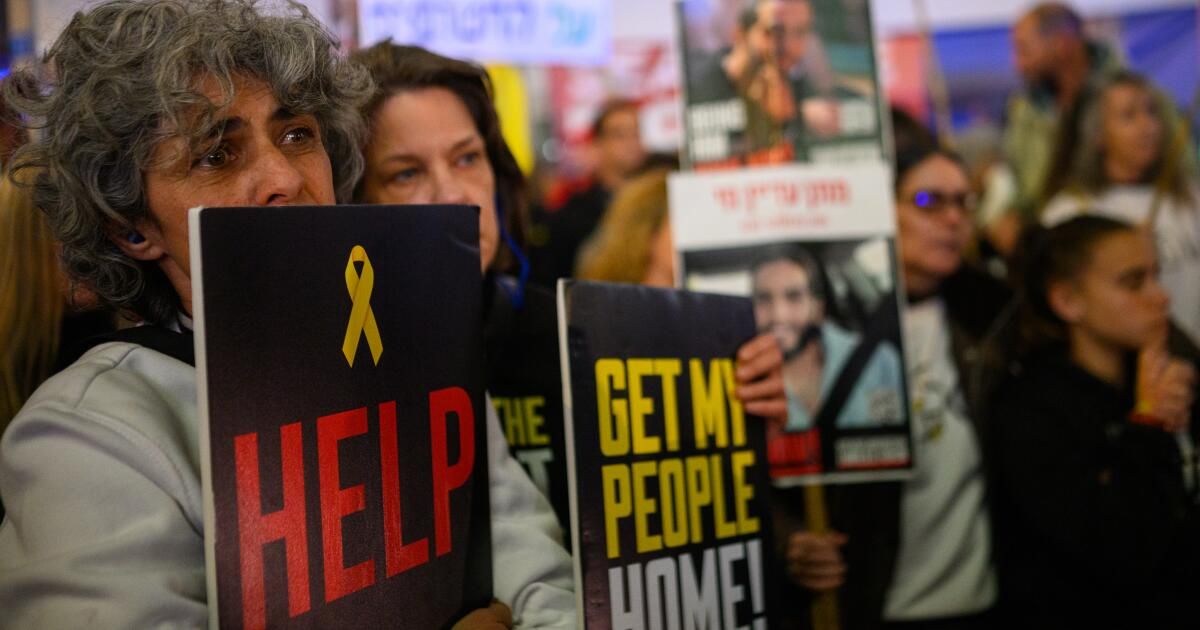

The original work title of my next book was “My partisan pain”, which is still the title of his first poem. I was surprised and angered that much of the artistic and poetic world had no interest in Jewish pain. It seems to me that no pain should be privileged or silenced.

Real peace can only be achieved through a calculation of pain and anger of the “other.” If artists and poets can't do this, how can we expect our politicians to achieve something? Opening the heart of one to the pain of the other, listening without judging the anger of the other, is the only route to cure a crack that grows by the generation.

I invite artists who have promised to boycott Israeli cultural institutions to read 10 of the 59 poems recently published in a bilingual edition of “Shiva: Poems of October.” Shuri Haza writes: “The table is full of empty space / hidden pain in holes and cracks.” Eva Murciano writes: “When I tried to write poetry / after that terrible day / the words fell face down on the ground.”

Yes, we are all mouth of the ground. Each Palestinian, every Israeli, every Jew.

I invite Boicoteros to open the pages of Yonatan Berg “Frayed Light”, translated by experts by Joanna Chen. I invite you to imagine a moment when, as Berg puts it in “after the war”, “the last ships have been defeated, the sea resumes / speaks alone. A black center / sinking behind the hills” and, more afternoon, of the same poem, “the earth returns from betrayal.”

Pause and repeat that line: “The earth returns from betrayal.” We have all betrayed this land that wants peace and coexistence. And it wouldn't be a betrayal? No Read and reflect on these lines simply because the writer is Israeli? However, I suspect that those who boycott Israeli cultural institutions feel that it is a betrayal to read Israeli poetry.

Self -imposed censorship destroys the possibilities of peace. Self -imposed censorship destroys that vital curiosity that makes artists prosper, which could take them behind enemy lines.

Through my poetry and others, I invite the thousands who supported a boycott to share the experience of an American Jew with family in Israel, one who wants to see freedom maintained for everyone in this country and peace and stability For everyone in the Middle East.

Naively, I affirm, we read poetry. We read everyone's poetry, as painful as possible. Naively, I ask, can poets speak? Can all The poets speak?

Owen Lewis is a professor of psychiatry in the Department of Humanities and Medical Humanities of the University of Columbia and author of the next collection of poetry “A sentence of six wings. ”