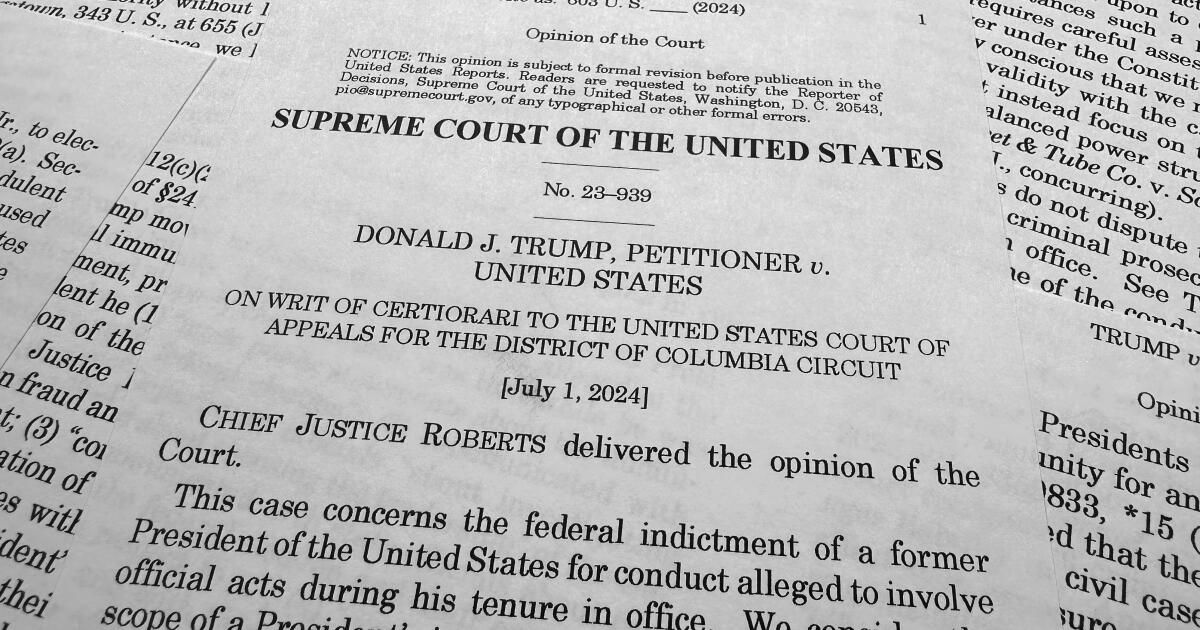

As Justice Sonia Sotomayor powerfully put it in her dissenting opinion in Trump v. United States, the Supreme Court on Monday “made a mockery of the fundamental principle of our Constitution and system of government that no one is above the law.” In a 6-3 decision, the six Republican-appointed justices handed a stunning victory to Donald Trump by broadly defining the scope of absolute presidential immunity from criminal prosecution.

Donald Trump was indicted in a federal district court in Washington for his role in attempting to undermine the results of the November 2020 presidential election. Trump requested that the indictment be dismissed on the grounds that his actions occurred while he was still in the White House and that a president has absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for anything he does while in office. Both the federal district court and the U.S. Court of Appeals rejected this argument, stressing that the core of the rule of law is that no one, not even a president, is above the law.

Though the Supreme Court didn’t go as far as Trump wanted, its ruling is a clear victory for him and future presidents. In an opinion by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., the court said a president has absolute immunity for his official acts. The court defined this expansively as any action taken in the exercise of the president’s constitutional powers or in the implementation of a federal law. The conservative majority then went further, saying, “We conclude that the principles of separation of powers explained in our precedent require at least presumptive immunity from criminal prosecution for acts of a president within the outer perimeter of his official responsibility.” And Roberts said a court cannot look to a president’s motives.

The breadth of this immunity is surprising. Imagine, to use an example raised in oral arguments, that a president orders the Navy Seals to kill a political rival. Under the court's approach, that would be protected by absolute immunity because it is an action taken by the president in the exercise of his powers as commander in chief. The court was explicit that the president's dastardly political motives are irrelevant.

Or imagine that a president orders the Justice Department to investigate and prosecute a political rival solely to gain political advantage. Or imagine, as Trump has already promised, that if he is elected president again he would use the Justice Department to exact revenge and prosecute his opponents. This, too, would clearly be protected by absolute immunity under the court’s decision. Indeed, Roberts wrote: “The President cannot be prosecuted for conduct within his exclusive constitutional authority. Trump is therefore absolutely immune from prosecution for the alleged conduct relating to his conversations with Justice Department officials.” Indeed, the court went so far as to say that Trump’s pressure on Vice President Mike Pence to ignore the results of the Electoral College decision carried a presumption of absolute immunity.

The court said that a president's private or personal acts, unlike official ones, are not protected by absolute immunity from prosecution. The court left open the question of whether there is absolute immunity for Trump's pressure on state election officials, such as in Georgia, and for his conduct on January 6. The court returned these issues to the lower courts to decide. But even this is a victory for Trump in the sense that the court did not state the obvious: these were undoubtedly personal and political actions.

It is for this reason that Sotomayor in her dissent says the justices “in effect completely insulate presidents from criminal liability.” As she puts it, it is “a broad view of presidential immunity that was never recognized by the founders, any sitting president, the executive branch, or even President Trump’s lawyers — until now.”

In the past, when the court has taken up issues like this, it has been unanimous and has stressed the importance of holding the president accountable and upholding the rule of law. In United States v. Nixon in 1974, the court unanimously held that President Nixon could not invoke executive privilege to thwart a criminal investigation. In Clinton v. Jones in 1997, the court unanimously ruled that President Clinton did not have immunity to protect him from a sexual harassment lawsuit that occurred when he was governor of Arkansas.

But we live in a very different and much more partisan time. It is impossible to interpret the decision in Trump v. United States as anything other than a court in which six Republican justices awarded a major victory to Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump. In fact, the way the court handled the case, denying the requested review in January and then not releasing its opinion until July 1, was itself a victory in ensuring that there is no way Trump could be tried any sooner. of the presidential elections of November 2024.

Roberts concluded his opinion by rightly saying, “This case raises a question of enduring importance.” Unfortunately, the court provided an answer to that question that undermines the rule of law and creates a serious future threat to our democracy by placing the president largely above the law.

Erwin Chemerinsky is a contributing writer for Opinion and dean of the UC Berkeley School of Law.