One of my patients who lives in Diné Bikéyah, the vast navajo reservation in New Mexico, he sleeps in an old Ford pickup truck that often won't start. He has heart failure and is dependent on oxygen. But since he has no electricity, he spends his nights sneaking into the Walmart parking lot to charge his oxygen concentrator so he can survive another day.

For more than a year, he has needed coronary artery bypass surgery. But he can't drive to the hospital three hours away and his friends can't afford the gas to take him. Every time your phone goes out of service, I wonder if it's a coverage gap or an unpaid bill. Or something worse.

These health problems are common on the country's largest reservation. American Indians have the highest mortality and lowest life expectancy of any racial group in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. My team's research shows that nearly half of American Indians who receive Medicare suffers from a serious heart problem. AND Life expectancy at birth of American Indians and Alaska Natives. was 65.2 years in 2021, equal to that of the general US population. in 1944.

These disparities are not genetic but rather a result of generations of land theft, unfulfilled treaty obligations, forced displacement, discrimination and indigenous genocide, all of which have fueled poverty and the worst health inequalities in our nation.

Many treaties that ceded tribal lands to the United States required high-quality health services in return. That's why the Indigenous Health Service was established. But the Indian healthcare system remains under-resourced and under-funded. IHS hospitals They are an average of four decades old, compared to the national average of 10.6 years; Veterans Affairs treats about 3.5 times as many patients as IHS, but employs 15 times as many doctors. The US government budgeted $4,104 per patient enrolled in the Indian Health Service in 2018compared to $8,093 per Medicaid enrollee, $13,257 per Medicare enrollee, and $9,574 per VA patient.

These numbers mean that Native Americans receive less care and die younger as a result. They perpetuate the message that an indigenous life is worth less than that of others.

There have been improvements in recent years. He The Supreme Court ruled this month that the federal government must cover related administrative costs for tribes that run their own health care programs. And last year, the government increased the IHS budget to $7.1 billion, representing a Increase of 68% in the last decade.. But those victories won't fill all the gaps.

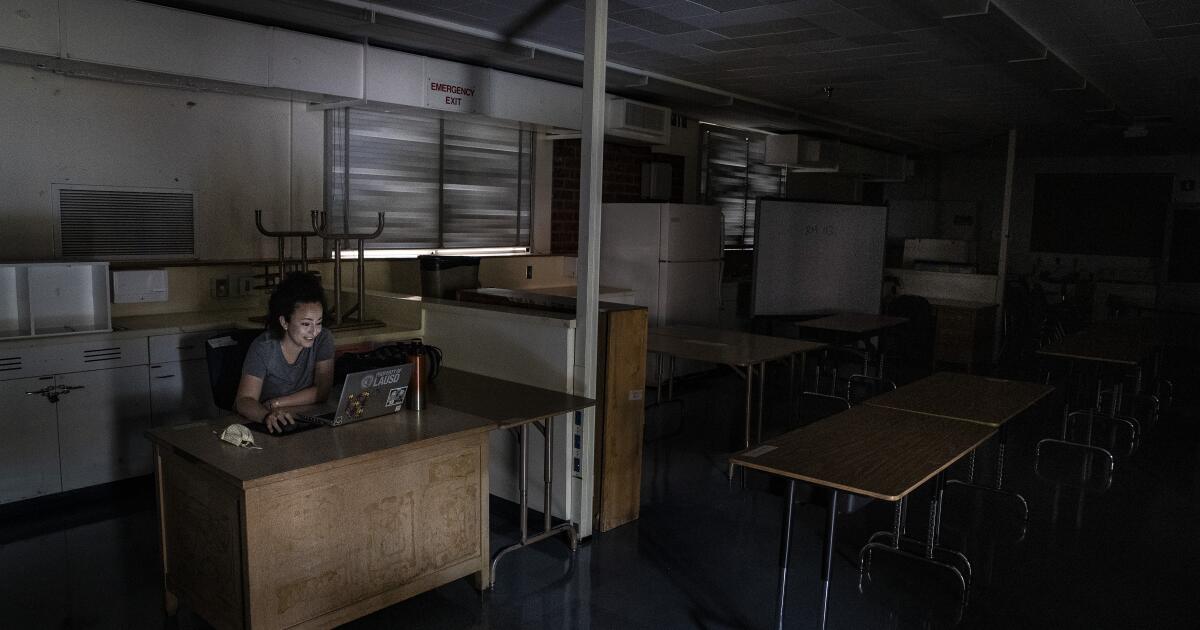

In it University of New Mexico School of Medicine, I worked with the Indian Health Service and saw firsthand the incredible burden of disease and widespread injustice. Now as an IHS cardiologist at Gallup Indian Medical Center and as a health equity researcher, I primarily focus on improving cardiac care for the Navajo community. The area has deep social needs: unpaved roads and inclement weather are common, poverty is widespread, and thousands of residents lack housing. electricity either water running. (Last year, the Supreme Court ruled 5 to 4, in Arizona v. Navajo Nationthat the United States is not obligated to guarantee the tribe's water needs throughout the reservation).

In the Eastern Navajo community, heart failure reflects the serious challenges to care. Only 23% of our patients used recommended life-saving medications. As our team thought about how to best serve this group, we realized we needed to listen—center the voices of the community. We had to reject the typical American model of care that relies on patients getting to the doctor, a process that benefits white, wealthy patients who face fewer barriers to receiving care. On the reservation, we can't wait for an elderly man to contact us when he is isolated in his house, unable to breathe and with his truck stuck in the mud 40 miles from our clinic.

With patient and community input, we designed and tested a proactive telehealth program to improve rates of guideline-recommended care. We reviewed the electronic medical record to find all heart failure patients in our system and contacted them to initiate therapy by telephone. This approach meant we didn't have to rely on in-person visits or limited broadband Internet access. Our Navajo-speaking nursing assistant performed weekly checks. Instead of waiting for patients to find us, we found them and provided care one phone call at a time.

The results, published in April by the journal JAMA Internal Medicine, were promising. Within 30 days, we increased patient use of proven drug therapies for heart failure by up to five-fold, far exceeding national use rates.

Of course, even the best care alone will never be enough. The Injustices Driving Health Disparities must be rectifiedand the social drivers of health they target. For example, Native American communities and their allies are working to increase access to fresh food and reduce the extreme underrepresentation of Indigenous doctors in the workforce. Center traditional cultural knowledge and Indigenous health practices It is also key. Research has found that incorporating tribal historylanguage and crafts are more effective for weight loss and blood sugar control than standard recommendations.

But access to care is a necessary start. Through our telephone program, we have reached more than 100 patients with heart failure. We identified eight who needed a life-saving procedure and helped them get it. After waiting 17 months, my patient in his old Ford truck is finally scheduled for surgery and our team will help him get there. As we expand the phone program to reach people with coronary artery disease and high cholesterol, the voices of our community members will guide us every step of the way.

Lauren Eberly is a senior investigator at the Leonard Davis Institute for Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania and an assistant professor of cardiovascular medicine at Penn Medicine. Her opinions are her own.