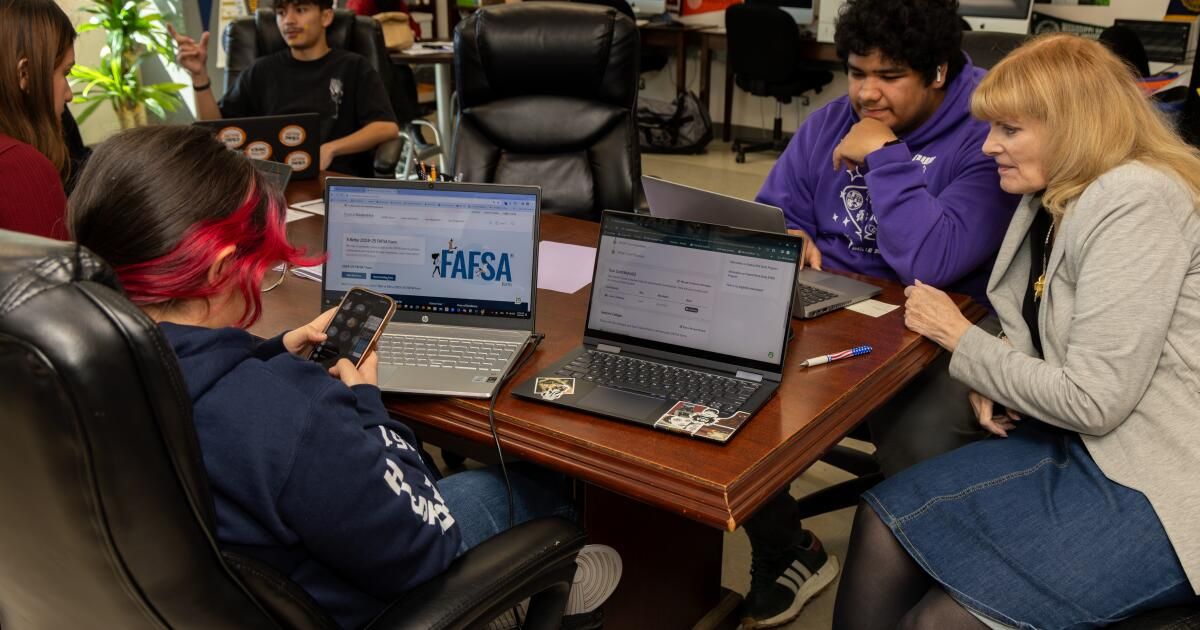

Thanks to delays in the Free Application for Federal Student Aid process, millions of potential college students and their families will have to wait longer than usual to find out what their financial aid packages will look like.

Completing the FAFSA is how prospective college students demonstrate their financial eligibility for aid to help cover tuition: Pell Grants, federal work-study, state financial aid, and federal loans. The bureaucratic, confusing, and often frustrating process adds to the anxiety many students and families feel when figuring out how to pay for college.

The FAFSA Simplification Act, which passed in 2020 and will be implemented for the next academic year, aimed to support more low- and middle-income families by simplifying the process, a laudable goal. The new system aims expand eligibility for Pell Grants and imports all participant information directly from the IRS to shorten forms, among other changes. But the launch was a failure. Parents and students reported several problems with the website. Many gave up; Applications were reduced in January, almost by half.

Failures in the system I hope it gets fixedand last week the Department of Education announced temporary measures to reduce the delay. But the uncertainty and instability facing low-income students hoping to attend college is not going anywhere. We need a simpler system of higher education financing that reduces instability and unpredictability in students' lives rather than increasing it.

Like most other policies in the United States, FAFSA prioritizes only those who “need” the funds. But when it comes to policymaking, there is a balance between targeting aid specifically and making it easy or even possible for people to get help.

Proving that you are worthy of college aid requires an elaborate means test or a demonstration of financial hardship comparable to what families have to do to qualify for welfare. Even if this approach is well-intentioned to protect the resources of those who depend on them most, these complex and demanding verification systems impose large mental costs on recipients. Many people who live in poverty and need financial support are already cognitively and emotionally overloaded. They are more likely to experience unstable housing and precarious employment. A health crisis or car accident may be enough to cause them to lose one or both.

Some students from poor families do not even apply to university, certain they will not be able to afford it. Those who do so are often unsure how they will pay until they hear about their FAFSA. And that's on top of the uncertainty they already face about where they'll live, how they'll pay for food, and whether their families can really afford to have them in college instead of working.

Students who are the first in their families to attend college and those from low-income families tend to have difficult financial situations. I know this firsthand: When I applied to college, my financial support was being cobbled together by several members of my family in a situation that would have been a nightmare to prove on the FAFSA. The only reason I avoided that hurdle was because, as an international student, I qualified for a blind aid package that finally made it possible for me to attend university and changed my life.

The child tax credit that many Americans received during the COVID-19 pandemic I was not completely blind to the needsbut similarly prioritized access over segmentation: Most families with children I received a monthly check in the mail. some saw the policy was a waste because well-off people with children also received checks. However, it was one of the most effective measures this country has ever taken to reduce child poverty.

Given the enormity of the college affordability crisis, it seems worth seriously pursuing solutions that also prioritize accessibility (e.g., baby vouchers, higher education vouchers, or, better yet, free public colleges).

Many have rejected free college as disproportionately wasteful and regressive. benefiting wealthy families. But that's because we're not taking into account the society-wide benefits of universal programs, such as the economic gains from investing in human capital and reducing student debt. Middle-class families will undoubtedly benefit; So will families in poverty who are already going through many obstacles trying to get the assistance for which they are eligible.

When we prioritize creating stability in people's lives, we give them the scaffolding to plan and aim for a better future. We should want all college students to enjoy that freedom.

Jennifer Morton is an associate professor of philosophy and education at the University of Pennsylvania and a Sara Miller McCune Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University.